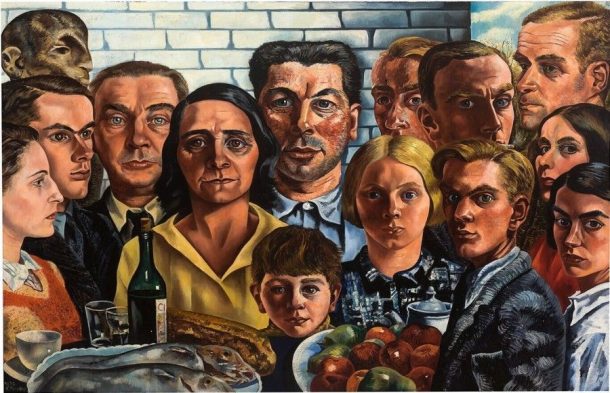

There is a painting I used to visit on a regular basis in Rotterdam. Titled ‘The Meal Among Friends’ by Charley Toorop from 1932-33 it is a sizable canvas that once held a prominent position in the enfilades of Boijmans van Beuningen. In 2008, while writing my master’s thesis at the Netherlands Architecture Institute, I would often stretch my legs procrastinate from writing by making a quick visit to the museum across the street, where I found myself returning repeatedly to Toorop’s work.

The painting is unusual in many ways – it is a group portrait, but rather than show each person in full, surrounded by a coherent background, the background is almost completely obscured by the exaggerated oversized faces of her subjects. The portrait is also not the usual collection of family members or members of a distinct organization, as is so common with such portraiture. Rather it is an assemblage of friends and family who Toorop felt a close bond with at the time (for design fans, that is Gerrit Rietveld in back in the light blue shirt).

The wall of faces, each one slightly covering the other is curiously not far from the modern-day aesthetic of the group selfie, where friends crowd into the frame, lens held awkwardly at an arms-length distance. But the effect here is something wholly other: Each gaze is different, each figure imbued with its own unique character yet taken as a whole we are presented with an unbreakable wall. It is akin to the proverbial bundle of sticks, exponentially stronger than any one individual.

Two weeks ago, I moved flats. It was a bittersweet moment. Over the course of lockdown, we – like many others in the UK – had come to know our neighbours far more than we would have ever expected. Thankfully, it was an overwhelmingly positive experience (not the typical neighbourly spats about noise and shared amenity spaces). In the absence of being able to see family or friends (the river more than ever in London seemed an uncrossable divide), we gradually broke out of our defensive shells to exchange small talk and tips for how to adjust to the evolving situation, with those that lived around us. Having just had a baby, we were able to socialize her with other human beings, not just the endless screen-time with our families abroad (as important as that was). Despite everything going on, these neighbourly good vibes, even if superficial, were a mental support; If not exactly the feeling of Toorop’s painting, it was something approaching it.

To a certain degree, community engagement can be framed as a design question. In a casual poll of friends, not all shared this neighborly revival like we did. What is the recipe for this success? Some of it of course is down to chance. But architecture and design here are also important. We live in a block of flats shared by one communal entrance, with a large yard in front. Those two elements were key to our interaction. Prior to the pandemic, almost nobody ever used the yard space, but during – with some encouragement from the landlord – it became a vital social condenser. It bears mentioning that financial security and job type were also a factor. Most of us were economically comfortable during this period, either furloughed, or working from home.

Much has been said about the revival of neighbourhoods during the pandemic. While city centres and places of work remained ghost towns, London neighbourhoods found a new energy. Park spaces worked overtime, becoming ersatz open-air community centres, gyms, and places to drink and eat with friends. While the hundreds of Pret a Mangers catering to commuter work culture languished, neighbourhood coffee spots thrived. A recent New York Time’s article discussed the resurgence of localism as an antidote to our increasingly globally networked culture and way of being – and the ideas of people like Helena Norberg-Hodge, part of a contingent of thinkers emerging in the 1970s championing action at the community scale.

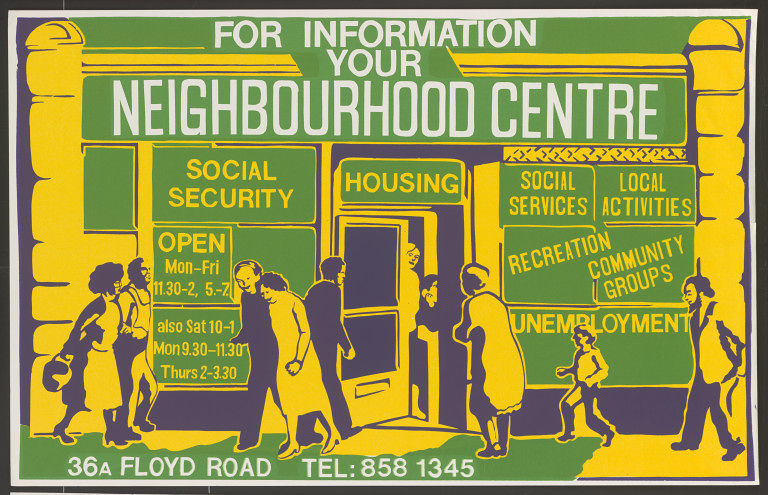

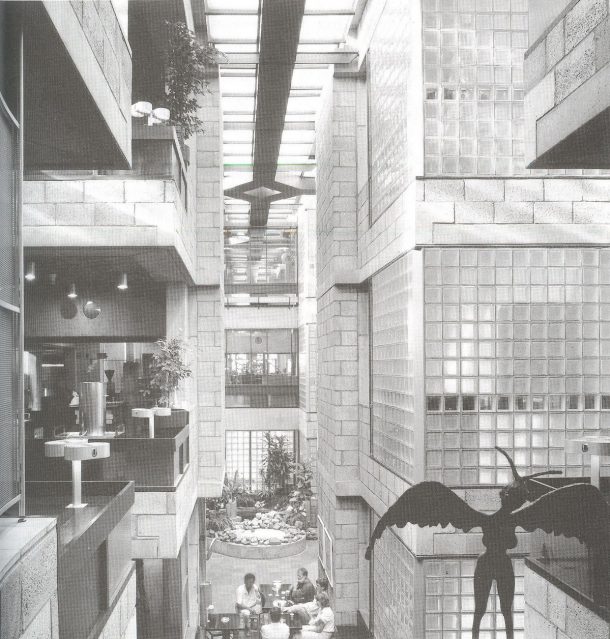

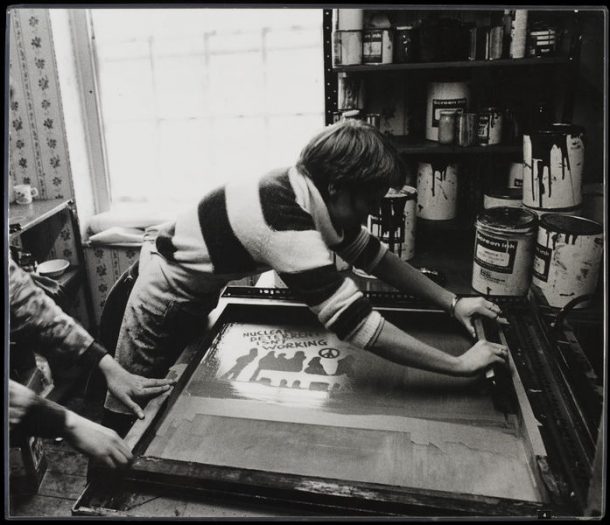

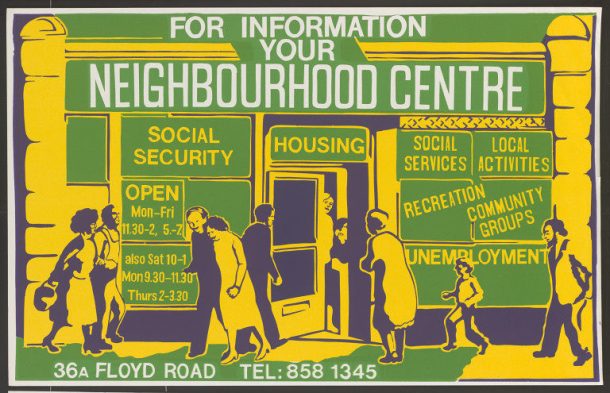

Indeed, the 1970s and 80s represent a golden moment where design explored community engagement and the local scale in exciting and creative ways. Hermann Hertzberger created office blocks (Centraal Beheer Apeldoorn) and seniors residences (De Drie Hoven) that implemented radical systems of mixing spaces of conviviality along with spaces that encouraged individual appropriation. In London, community print workshops sprouted up across the city to support the poster campaigns of local organizations. The V&A has a collection of these posters which appeared in the 1986 exhibition ‘Printing Is Easy’ organized by the Greenwich Mural Workshop. In the 1980s, Dolores Hayden in Los Angeles created the non-profit The Power of Place, which brought together community members, geographers, artists and planners to commemorate forgotten places and local legacies. This is to name but a few of the many design-led projects that worked in the realm of neighbours and community.

Returning briefly to Toorop’s work, there is an oft repeated idea in the Netherlands called the polder model, a form of consensus-based decision-making and of cooperation despite differences. The term comes from the landscape feature of polders, land reclaimed from the sea protected by dykes and requiring regular maintenance and drainage, which constitutes much of the country’s geography. Because of the need for cooperation amongst individuals to both build and maintain the landscape, a form of nuanced community engagement and negotiation emerged as an engrained cultural practice in the country. Neighbourliness forced by the impetus to survive.

However, the polder model has arguably frayed over the years. Like elsewhere, a strong sense of individualism has ruled politics both in the Netherlands and around the world. There’s much discussion today about what we would like to keep from the experience of the last six months. While much of it has been inarguably bad, certain experiences at the community level have been revelatory – a reminder of the power that local amenities, good neighbours, and a slower pace of life can bring. When the pandemic subsides, many fear that it will be far too easy to slip back into our old ways and habits. To avoid that, projects that explore how interaction and engagement can be designed and facilitated to bring us together are more urgent than ever.

Further Reading:

‘Do You Know Your Neighbours? Thanks to Lockdown, I Do’, Krista Burton, The Guardian, 28 May 2020.

‘The Meal Among Friends’, Charely Toorop, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen.

‘Play Streets in New York, a Safe Haven Designed to Thrive’, Susana F Molina, The Urban Activist, 6 August 2020.