This piece contains references to drug use.

To insert, to open, to wound, to part lips, to enquire, to seek, to help, to repair, to construct, to heal, to kill, to hurt, to harm.

A hospital ward somewhere in the UK.

My doctor said he’d give me a perfect vagina; one I can have sex with he meant. After surgery he came close to my bed, in kissing distance, with a tray of single-use plastic speculums, not 3D-printed speculums but factory produced, mass produced. The anonymous plastic throwaway mass-produced object was to enter my deeply personal sacred space. I need to trust him and technology.

My vaginal space was both magically and surgically created.

This scenario was no different from a thousand others, a thousand other speculums in a thousand other places. Wards. Clinics. Sterile. Women of all kinds, being opened and parted by patriarchy, by structures and systems that demand we open up and structures and systems that our bodies need. We’re tied into this scenario. The speculum scene. It’s one that needs to be kind and safe.

Meanwhile, many years ago, in a previous life of mine, a drug deal had gone bad. Gone South, as they say. I felt the cold tip of a small, compact metal handgun press on the edge of my lips. At an entrance to my insides, my being.

‘Open your mouth,’ he said.

‘Wider,’ he said.

‘Now close your lips around the gun,’ he said.

The gun entered my mouth, its barrel was smooth and cold. It terrified me in a way that made me float up and leave my body. In the air above I tried to silently count my fear away.

One, two, a hundred, five, six, fifteen, ten. It didn’t work.

Meanwhile, in my new drug-free life, the doctor pushed the single-use plastic speculum deep into my newly created cavern. My neo vaginal space. The space that was brimming full of transformative wonder now reduced by his pushing the speculum into my maximum depth and telling me that I was six inches deep. Like a pond. Like a shallow river. Like a bad poem. Six inches deep.

I felt violated but I didn’t know why. No one had pushed a speculum into my vagina before because it only came into being five days before. But then I remembered the handgun.

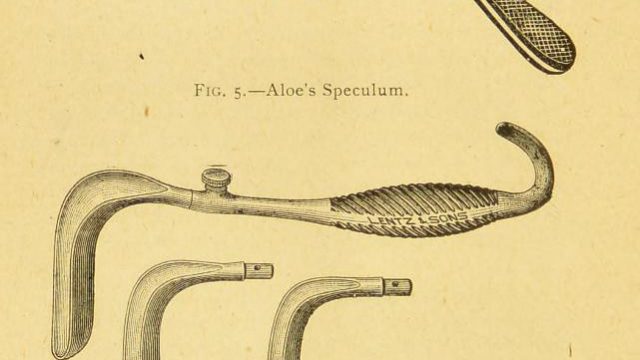

He was my first speculum. A device made, molded to fit the hand of the user. A device which opens us, me, up to the world. To scrutiny. To saviour. Its molded smooth, silky plastic body enters me like a punter hoping a tip will get them extra. Trying to be smooth, flashing a fiver. The speculum so silky it runs over my ridges – stitch lines, which bind my new space together like a homespun quilt from the American plains. The pain I endure so he can tell me my depth for men is immense. Is this the way it’s going to be I wonder.

A tear falls onto my hospital gown. It’s angry salty it burns and falls five floors into a reception.

Meanwhile, back on drugs, many years ago, gun in mouth, I’m levitating out and above my body, I look down at the man’s hand holding the handgun in my mouth and wonder if he would pull the trigger. I try to regulate my breath into the slightest of movements. Into non-movements. It was so easy for him to enter this space of mine with the handgun hidden in his hand and so easy for the trigger of the gun to sit in his hand and the barrel in my mouth.

Why do gadgets, instruments, buildings, chairs, heights, weights, surfaces, materials work for men and not for us. Why are we thinking about needing to make our own. To step outside of structures that should be safe.

Meanwhile, now, eleven years on from one event and twenty-five from the other, I sit and look at two photographs, one of a 3D-printed speculum and one of a 3D-printed gun.

The barrel of the 3D-printed gun is completely smooth, baby-soft skinned, printed white, angelic almost. The grip is textured for a hand to grip. As if to offset the angelic soft ethereal white barrel, the handle, the grip, is printed in the darkest grey of night. 3D-printed guns aren’t durable, but they will fire lethal rounds. They will do the work of men, of the patriarchy. They will control. They will instill fear.

The 3D-printed speculum, the punk reclamation of female genital investigation, seems rough, many ridges remain from the printing process, like my vulvic stitch marks. The rough lines, edges that delineate a printing pause or a change of computerized instructions. Stop, turn, smooth, move, stop.

A breath in the process which becomes a row of minuscule plastic nodules. I wonder to myself why the punk-open-source-speculum gives us yet more ridges to climb over. Like we don’t have enough.

Meanwhile back in the early 2000s on a hospital bed a doctor tells me that I have enough depth for an average penis. An average penis being more than enough, he felt, for most women like me.