Object pitch day 1 – Wednesday 3rd September 2014

For the first phase of ‘A history of an OBJECT in 100 worlds’, we invited staff from across the V&A to help us identify the ideal object of focus for this collaborative project by responding to the following question:

“If you were asked to choose the object of focus for a project called ‘A history of an OBJECT in 100 worlds’, what object would you choose and why?”

The rules of the game are simple. Each participant is accorded a maximum slot of 5 minutes to make their case. They begin by introducing themselves, then pitch their object of choice and argue for their reason(s) for choosing it. Time is kept very strictly by Bill Sherman, the V&A’s Head of Research, and is the most formal element of the proceedings. Any style of presentation – formal, academic, humorous, performative, etc. – is valid, and all kinds of ways of addressing the question – intellectual concerns, practical reasons, personal or emotional responses, etc. – are encouraged: the more wide-ranging the approaches the more informative the exercise will be!

Attendance was great at the first ‘object pitch’ event, which took place at lunchtime on Wednesday 3rd September. The Research Seminar Room was filled with staff from across the museum, all curious to hear other people’s pitches, some of them would-be-pitchers trying to get a sense of how things will unfold in preparation for their own pitch day.

Four highly stimulating and quite different pitches were presented on the day. They generated enthusiastic applause as well as some laughter from the audience, demonstrated a diversity of approaches to the project’s underlying question and set a very inspiring tone for the project at its opening event.

OP1/01

‘Young Man Among Roses’ by Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619) was the first object pitched, and was presented by Susan Hughes. As the V&A’s legacies and bequests manager, Susan gets to see all kinds of objects from across the Museum’s departments, and this particular one, she said, epitomises what legacies are about at the V&A.

‘Young Man Among Roses’ is one of the first legacies that entered the V&A collection. It is a portrait miniature by Nicholas Hilliard, master painter of Queen Elizabeth and founder of the art of the Elizabethan miniature, and as such it constitutes an opening into the Elizabethan world. It is further thought to represent Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, the son of Lettice Knollys who married the Queen’s favourite Robert Dudley and incurred her wrath. So, as Susan put it, “there’s quite a lot of worlds there to explore”. [See this article by Roy Strong]

The object entered the museum in 1910 but, beyond the first decade of the 20th century, we have no history of it, a 400-year gap and lots of questions that, Susan suggested, it would be very interesting to look into.

It was bequeathed by George Salting who donated one of the biggest collections to the museum as a legacy. Such bequests, Susan explained, are the basis of the diversity of the collection.

Salting’s own story, she continued, also opens up many interesting worlds. Salting was born in Australia to Danish parents in 1835. In 1858, his family moved to Britain, where his mother died in that year. Salting attended Balliol College, Oxford, for one term before joining his grieving father in Rome, where he learnt a lot about art and architecture. In 1865, his father died, and he inherited the fortune that allowed him to become a prominent art collector. Salting was passionate about collecting and started loaning objects to the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) from 1874, often leaving them there on deposit and helping the museum in that way with its diverse collections.

The miniature is captivating and a famously popular object: it has featured in a BBC documentary in which art historian Dr James Fox confessed that if there was one piece he could steal from any of the many museums and galleries he visits, this would be it.

The idea that it’s a portrait miniature, an intimate keepsake, is very charming: Where has it been? Who was is for? Where did they keep it? How many times did they sneak a look at it? “Lots of things to explore”, Susan concluded, “I hope you’ll take me up on that!”

OP1/02

The next pitch was by Rozi Rexhepi, a member of Berlin-based design collective T-Shirt Issue who have been digital design residents at the V&A for the past five months.

Rozi said she was really happy to be able to pitch an object for ‘A history of an OBJECT in 100 worlds’ because it had pretty much been T-Shirt Issue’s job to go through the museum and find objects that they like, from which they could produce 3D scans to turn into new art projects.

The object she pitched is ‘Death as a drummer’, or “this guy” as Rozi referred to it, one of the first things they saw in the collection that really “wowed” them.

What is this? Who made it? When was it made? They were surprised, she said, by the year in which it had been made.

The thing about this object, she continued, is that everybody understands that its source is the medieval belief that the dead come out at night, dance on the graves, joining hands with the living in order to remind us of where we are all going in the end (the Danse Macabre).

The depiction of this skeleton banging on drums makes you laugh at first, but it soon becomes clear that the future is quite gloomy for all of us. Its baroque style, Rozi explained, makes it very dynamic and overly dramatic, so that “every time I have to laugh at it but still it makes me quite sad”.

The statue itself is quite small (27.5 cm), but it nonetheless demands that one comes back to it quite often because it’s so powerful. This, Rozi suggests, is due to a combination of precise execution and an enduring theme. Death, in her opinion, supersedes all other themes in art, because, even if it’s the only certainty in life, “it is something that we can’t grasp and so the best we can do is to portray it”. The technique and aesthetics involved in the object also make it timeless – “This guy could be a 2014 rock star!”, Rozi exclaimed, “and he looks like he could have been 3D-printed as well, spanning years and technique, and staying relevant even today.”

In addition to this, of all the objects that T-Shirt Issue were inspired by across the Museum, ‘Death as a drummer’ was the only one that wouldn’t allow itself to be 3D scanned – a frustration that definitely contributed to its overall effect on them.

The reason it should be this project’s object of focus, Rozi concluded, is simply that they are “smitten by this guy”, and would love to explore some of the worlds that might be behind its particular affective power.

OP1/03

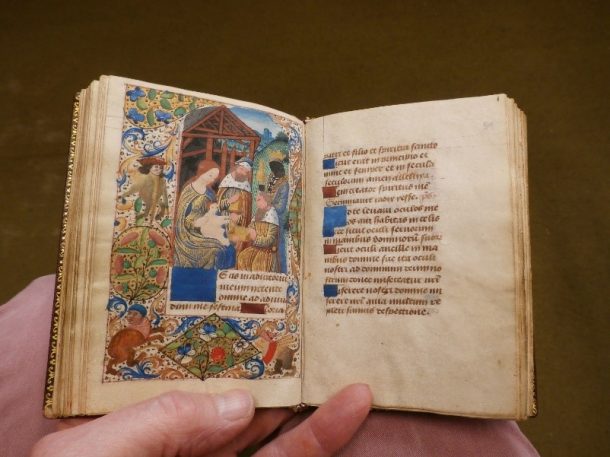

The following object was physically brought in to the seminar room by Rowan Watson, senior curator in the Word & Image Department: a pocket-sized 15th-century ‘Book of Hours’.

“The thing about this object”, Rowan said holding it up, “is that it isn’t finished and yet in spite of that it could function as a prayerbook”. A dreary binding in brown leather: this was actually quite chic at the time: when Queen Victoria gave bibles or improving books to her friends, they were usually bound in leather of this colour. The manuscript was bound by Edmond Fleur who was operating in Paris just after 1900; so there was interest in it then, at a time when these illuminated manuscripts were, in a way, icons of the Catholic classes who resisted all the activities of the progressive Third Republic. The inscription ‘LIVRE D’HEVRES’, has a ‘V’ for the ‘U’, a knowing anachronism. Rowan hasn’t yet discovered the meaning of the date ‘1402’.

This book is an intriguing object: when you open its nineteenth-century binding, as Rowan demonstrated, the first page of the original book is terribly worn, though the calendar (the usual prefatory text for a book of hours) is still legible. Books of Hours were mass produced objects. The worn first page suggests that the manuscript didn’t have a binding for part of its working life. This quality of ‘unfinished-ness’ is key to Rowan’s case for choosing the object.

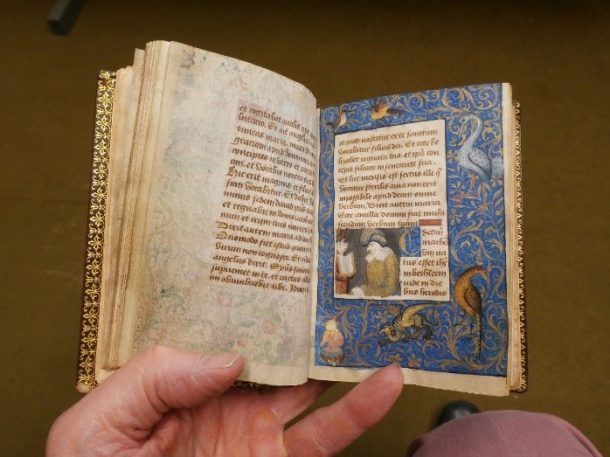

Another striking characteristic about this object that is also related to it being unfinished, is the varying states of completion of illuminated miniatures and initials on different pages. Ranging from pages with only the red and blue square grounds of the initial, through to examples where a simple initial in brush gold is added onto the square, to ones elaborately produced with intricate detailing, these give insight into the manufacturing process of such books and suggests a type of division of labour with different individuals responsible for different tasks.

Images, an integral element to all books of hours, also appear in different stages of completion, sometimes on the same spread, further supporting the idea that the series of unbound folia constituting it were worked on by different people and probably at different times. They are also evidence of a particular drawing technique in which the various illustrators would have been trained so that their combined efforts would result in a specific stylistic coherence.

The element that Rowan finds most endearing about the object, however, is a much more discreet one, or rather a subtle relationship between two elements: the first an inscription in French stating ownership of the manuscript, “J’appartiens à Harreteau”, written in a very good hand, an early 16th century legal hand, in an inconsequential place on an insignificant page; the second, a scribble at the top of the first recto, that seems to have been made by someone not entirely literate attempting to copy the earlier inscription, possibly to mark the object as their own.

Prayers added to the original manuscript suggest that this was a functioning object in continued use from the 15th century onwards. All these elements also offer physical evidence of the practice of circulating unfinished books of hours within the book trade, which could be personalised for specific customers at the point of sale.

“The significance of a manuscript like this”, Rowan concluded, “is the multiplicity of inputs that went into making it”. It warn us that any surface need not be the work of one maker, but can be the result of several makers each with a separate skill.

OP1/04

Pitching the final object of that day, Kirstin Kennedy, curator in the Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics and Glass Department, confessed that one of the reasons she chose the ‘Lomellini Ewer and Basin’, is that this allowed her to put forward two objects instead of just one.

A ewer and a basin are, in principle, Kirstin explained, functional objects. They were used for handwashing at table: water poured by one servant from the ewer splashed over the diner’s hands and into the basin held below by another servant. This ewer and basin weigh about 4.5kg each, however, so they were more likely to have been objects made for display.

The pair are made of silver and were marked by the Genoa assay office at slightly different times. The basin bears the mark for 1621, the ewer for 1622. Both are also stamped with the initials ‘GAB’, probably the maker’s mark of the Flemish goldsmith Giovanni Aelbosca Belga, who is recorded in Genoa at this time.

Unusually for silver of this date, Kirstin argued, the design source and early circulation of these pieces can be traced. Elements from some of the scenes of ships, surrender and prisoners embossed on the ewer and basin correspond to sketches for a now-lost fresco by the Genoese artist Lazzaro Tavarone for the palace of a leading Genoa family, the Grimaldi. The connection with the Grimaldi family continues with the subject-matter of the densely-populated scenes on the ewer and basin. These commemorate their triumph over Venetian forces in 1431, and the Grimaldi family arms appear on flags and shields on the ewer. Recent research suggests these splendid pieces were probably commissioned for Onorato II, a member of the Monaco branch of the Grimaldi dynasty.

Shortly after they were commissioned, the ewer and basin passed to the Lomellini family. Their arms have been applied prominently to the centre of the basin and the body of the ewer. The Grimaldi arms, however, have not been erased, which suggests the ewer and basin were presented to the Lomellini family as a gift. An occasion likely to have prompted this generosity is the wedding of a member of the Grimaldi family, Barbara Spinola, to Giacomo Lomellini around 1620. After the wedding, the ewer and basin seem to have undergone yet further alteration to reflect family fortunes. In 1625 Giacomo was elected Doge and became one of Genoa’s ruling élite. The Doge’s crown which surmounts the Lomellini arms was probably added in that year to commemorate this significant event.

The Grimaldi/Lomellini ewer and basin now in the V&A are also a magnificent supplement to the original commission of wedding plate made by the Lomellini family in 1519 for Giacomo and Barbara’s wedding. Two smaller, silver ewers and basins now in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford and in Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery are embossed with the Lomellini arms and depict mythological scenes appropriate to a seventeenth-century marriage, including Venus, goddess of Love, and nymphs being carried off by satyrs.

The three pairs of ewers and basins were still together as a group in the early nineteenth-century, although in the meantime they had travelled to Naples. In 1807 they were all acquired there by the 5th earl of Shaftesbury, who added sturdy square bases (engraved with his own arms) to the ewers.

The pieces stayed in his family until 1973, when they were auctioned at Christie’s and saved for the Nation with the help of The Art Fund.

***

Four pitches putting forward very different objects, but also suggesting a diversity of reasons for choosing an object. What makes an object talkative? What kind of stories would we like an object to tell? What kind of lessons do we want it to present? Is is best to go for an object with a traceable history or one we know very little about? Should we choose the object that has travelled the most? The one that has changed most? What is the most connected object?

As well as excellent cases for each of the objects, the pitches offered us a very enjoyable glimpse into our colleagues’ object worlds and the chance to learn more about the Museum’s collection.

More soon with a report on the following pitch date which took place on Friday 12th September!