How do you create a drawing in space? What you need is a linear element that can be held in tension, left to droop, crossed and tangled – just like a pencil line (which can be ruled, freely drawn, and overlapped). String is the thing.

How do you create a drawing in space? What you need is a linear element that can be held in tension, left to droop, crossed and tangled – just like a pencil line (which can be ruled, freely drawn, and overlapped). String is the thing.

The use of string as a drawing medium goes way back in history, in the form of the “chalk line.” Below is a historical recreation of the type of reel-mounted chalked string that a 17th century carpenter would have used. (It was made by Peter Follansbee, who demonstrates historic woodwork at Plimouth Plantation in Massachusetts.) Its use is simple: it can be dragged or, better, snapped along a board to mark a line for cutting or joining.

I like to think of the chalk line – a preparatory design tool, like most of the drawings discussed on this blog – as the primordial ancestor of a whole range of 20th century string-based art. My favourite example is Marcel Duchamp’s devlishly clever work Three Standard Stoppages.

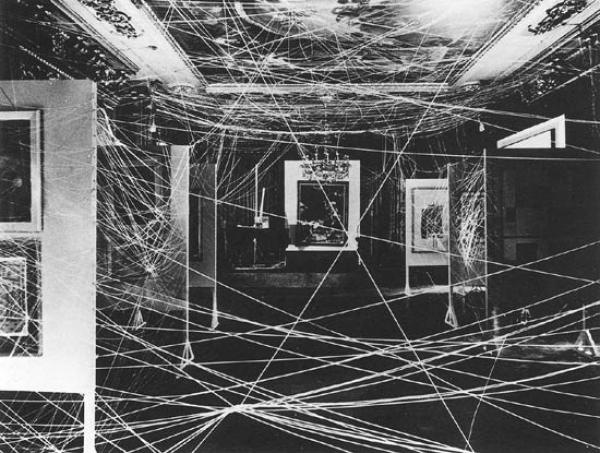

To make this piece, Duchamp repeatedly dropped a single meter-long length of string, and marked the random pattern it made when it fell. He then made stencils using these profiles, adopting them as a ‘found’ measuring tool (much as he used found objects in his Readymades). He obviously liked string, because he later filled a whole gallery with it: sixteen miles, to be exact.

Sixteen Miles of String is often described as an early example of installation art – it’s not so much a sculpture as an environment. It also anticipates many later, similar artworks, including the intricately crafted constructions of fiber artists in the 1960s and ’70s like Lenore Tawney, whose work is shown to the left (and discussed brilliantly in Elissa Auther’s recent book String Felt Thread), as well as better known artists such as the post-Minimalist sculptor Eva Hesse…

…Fred Sandback…

…Tony Cragg (as mentioned in a previous blog post)…

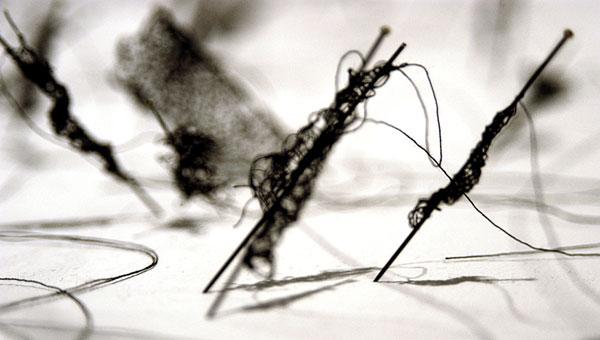

…and, more recently, the Chicago artist Anne Wilson, who was featured in the 2007 V&A exhibition Out of the Ordinary.

In all these cases, artists ‘draw’ with string in mid-air. But there’s one key difference between these works and a drawing you might make on a piece of paper, and I don’t mean the difference between two and three dimensions. For a carpenter, the whole point of a chalked string is that it can be used to create a line ‘automatically,’ without you having to execute it by hand. The string has a movement of its own. You can see the same thing happening in all the works shown above: the way the string curls and sits of its own accord in the Hesse, strikes out into lines of colour in the Sandback, or snarls and crawls into animate form in Wilson’s tabletop landscape Topologies.

As so often, Duchamp got there first: the Standard Stoppages show how materiality can be an alternative to intention, dictating form whether we like it or not. He had the humourous idea that this could be systematized, made into a device (he called it “a joke about the meter”). Other artists have exploited the same concept more expressively. But no matter how you look at it, a drawing made with string is a welcome reminder that any sketch is made from something; and that material is always going to have its say.

* For more on string in art and craft, see this special issue of Textile: The Journal of Cloth and Culture.