Of all the talented women textile designers of post-war Britain, Lucienne Day's influence is the most far-reaching.

Graduating from the Printed Textiles department of the Royal College of Art in 1940, the effects of the Second World War initially limited the prospects of design work, and Lucienne Day supplemented her design career with teaching roles. However, as the restrictions of the war began to lift, she quickly built on her relationships with existing manufacturing clients to produce modern furnishing textile designs. A receptive audience was waiting, ready for a breath of fresh air after the visual bleakness of the war years. Along with her husband, furniture-designer Robin Day, she promoted modern living and embodied the image of the newly styled professional designer.

This deferred launch of Lucienne Day's career coincided with a major governmental initiative to boost the nation's industrial production by elevating the status, training and consequently the output of British designers. Both Lucienne and Robin fulfilled the brief perfectly: ambitious, highly talented and with a committed vision of the life-changing potential design could bring. By the end of the 1940s Lucienne Day had found work with Edinburgh Weavers, Cavendish Textiles (the John Lewis house brand) and Heals.

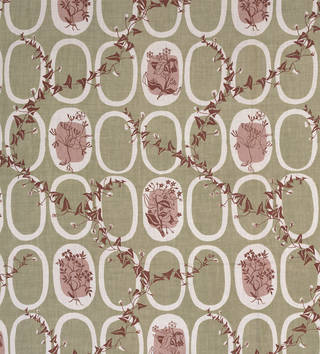

Although Day was already creating progressive designs for the dress industry, her first commercially produced furnishing textiles were not overly avant-garde, loosely acknowledging the long-favoured tradition of floral chintz for home furnishing fabrics. Day believed that a designer must be practical and meet market needs – her early designs were well-judged to appeal to traditional consumer tastes. Their success brought her further commissions and set her on the path to become a sought-after freelance designer.

'Calyx' and the Festival of Britain

In 1951 the perfect opportunity arose for Day to work outside of the constraints of a straightforward commercial commission. Her husband Robin had already secured the commission to design all the seating for the Royal Festival Hall, the newly-built auditorium and concert hall constructed on London's South Bank as part of the Festival of Britain – a major exhibition intended to showcase Britain and its achievements. He also designed room settings for the Festival's Homes and Gardens Pavilion, which showcased his own contemporary furniture.

For these room settings he needed a wallpaper and furnishing fabric that would sit comfortably with his modern furniture. Provence wallpaper, a previous design by Lucienne Day, was chosen for one room to illustrate an affordable interior. Lucienne also conceived a new textile design, Calyx, intended to complement Robin's more costly living/dining room. Heals were initially hesitant to support the design due to its radical nature – it was a huge leap on from the type of pattern compositions found on fabrics at the time – but they eventually agreed.

Calyx uses a very traditional source of inspiration, botanical form, (in botany the word calyx refers to the outer parts of a flower), but the plant motifs are here stylised almost to the point of abstraction, and are linked with diagonal and vertical thin solid and dotted lines, suggesting flower stalks. The design embodies the springing energy of new growth, perfectly encapsulating the spirit of the Festival and general social optimism of the time.

Plants and the sense of growth – the sense of growth more than the plants, the kind of upward movement – was an important inspiration.

Contrary to their fears, Lucienne Day's new design turned out to have great market appeal and became one of many commercial successes in a long-standing partnership between Heals and the designer. It is now recognised as a seminal piece of British post-war design.

Inspiration and influences

During her training at the Royal College of Art, Day spent many hours in the galleries of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Here she found inspiration for her degree show, in the form of a Chinese sculpture of a horse. In her design, Horse's Head, the horse is refined to a simple motif, which is alternated with fluidly drawn squares, hand-printed onto linen. The Museum's collection provided inspiration again for Script (1956), drawn from a poem by Maulana Jalal Al Din Runi. Botanical form was an important source of inspiration throughout Day's career – her treatment of this theme provides much of the visual delight and innovation in her designs.

In Trio (1954), small groups of flower-like forms stand upright against a striped background. In Herb Antony (1956), plant elements are transformed into graceful line-drawn forms that take on a unique character, hovering between reality and imagination. In her highly thoughtful approach to design, Day also benefitted from an appreciation of contemporary fine art as well as possessing something of an artist's sensibility herself. The absorbed influence of the work of artists such as Juan Miró and Paul Klee can sometimes be perceived – and in many cases Day's work can be seen to anticipate or equal fine art influences. Graphica (1953) for example, is a highly accomplished minimal geometric abstraction and Causeway (1967), a brilliant execution of colour block contrast.

Regardless of the increasing celebrity status of both her and her husband, Lucienne Day remained committed to answering the material needs and demands of the consumer market. While the large scale, printed linen Calyx worked well in spacious interiors, hung from ceiling to floor, Heals also requested designs to suit smaller homes, and with a more modest price tag. Enthusiastic to produce affordable textiles, she embraced newly developed and cheaper man-made fibres, such as rayon. Flotilla (1952) and Lapis (1953) were produced with this in mind. She designed Miscellany, Quadrille and Palisade, all 1952, for British Celanese – a company that specialised in producing man-made fabrics from cellulose fibres, which were affordable as well as being soft and durable. In the later 1960s, her designs moved with the spirit of the times to larger geometric based pattern in bold colours, illustrating her ability to adapt and evolve. Apex (1967) and Sunrise (1969) remained favourites of Day's.

Though Lucienne Day is best-known for her patterns for furnishing fabrics, she also produced designs for many other applications. Dress fabrics were an important part of her design practice in the early post-war period. With companies such as Cole & Son, Crown, and German company Rasch, she collaborated to produce several successful collections of wallpapers. Diabolo was one of three wallpapers launched at the Festival of Britain in 1951. During the 1950s and 60s she produced a substantial body of carpet designs for Tomkinson's Carpets and Wilton Royal, including Tesserae which won a Design Centre Award in 1957. Some of her most loved designs were for a series of tea towels for the Irish linen company Thomas Somerset, which include Too Many Cooks, Bouquet Garni and Black Leaf (all 1959), which was also recognised by a Design Centre Award in 1960. During these productive decades of her career, Day also collaborated with the prestigious German manufacturer Rosenthal, creating elegant designs for their china tableware, such as the Four Seasons series.

The silk mosaics

Lucienne Day was skilled at adapting her designs to the requirements of a commission, and her designs were constantly progressing. But the return to traditional floral patterns and 'period' style that took hold in the late 1970s was not to Day's taste, and she began to feel less engaged with manufacturing design. Her belief in modernism was steadfast and she was not intent on adapting to this market. Needing a new channel for her creativity, Day started creating one-off compositions in silk. Using a construction technique derived from traditional patchwork, her 'Silk Mosaics' are composed of 1 cm squares and strips of coloured silk. The design emerges through carefully juxtaposed blocks of colours and weave textures. These creations occupied the decades of the 1980s and 1990s for Day, as she prepared them both for exhibitions and commissions. Aspects of the Sun (1990), a work comprised of five large-scale silk mosaics, was commissioned for the café of a new John Lewis store in Kingston, and was hung in 1990. A playful series of six silk mosaic works called Decoy and Pond (1983) is now in the V&A collection, along with the more abstract Flying in Blue (1985).