Flock wallpaper was originally invented to imitate expensive cut-velvet hangings. Traditionally it was created by adding 'flock' – a waste product of the woollen cloth industry, which came in powdered form – to an adhesive coated cloth to create a raised velvet-like textured pattern or design. Today 'flock' has been replaced by man-made fibres such as polyester, nylon or rayon.

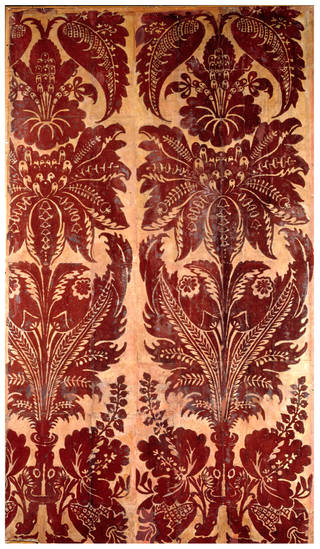

It is not clear when the first flock wallpapers were produced, but trade cards and advertisements show they were available by the late 17th century. By the 1730s many flock papers that were direct imitations of damask (a rich, heavy silk or linen fabric with a pattern woven into it) or velvet began to appear. The range of patterns available at this time seems to have been relatively limited. One particularly magnificent design has been found in several locations. This was a crimson flock on a deep pink background, which has faded to yellow on most surviving examples. This pattern was hung in the offices of His Majesty's Privy Council, Whitehall, London, around 1735, as well as in the Queen's Drawing Room in Hampton Court Palace and in several town and country houses, also in the 1730s.

Flock papers proved extremely durable – certainly more so than the textile hangings they imitated – and so although they were relatively expensive in comparison to other contemporary wallpapers, they were nevertheless good value for money. Flock papers also had an advantage over textile wall coverings in that the turpentine in the adhesive used for fixing the flock kept them free from moths.

The designs themselves also proved to have a long life, with several of the large-scale formal patterns – notably the so-called 'Privy Council flock' (now usually known as 'Amberley') – continuously available to the present day. Although flock papers have been produced in every passing style, the designs of the early 18th century have survived as a sort of gold-standard for good taste which stands outside changing fashions.

The grandest flock papers have a large repeat pattern, often six or seven feet in length. Papers on this scale were intended for large formal spaces – the public and semi-public rooms of great houses. Sometimes, papers were flocked in more than one colour which produced a richer, more luxurious effect. Large-scale Baroque patterns, symmetrical around a vertical axis, were appropriate in formal settings and large rooms but were not used in more modestly-sized private rooms. For these rooms small-scaled flocked patterns were available, ranging from simple patterns to asymmetric floral designs similar to contemporary silks. A paper of this kind, with a yellow background, blue-stencilled colour and dark-blue flock, was used in a bedroom at Clandon Park in Surrey.

The designs of flock papers were swiftly adapted to changing fashions. The earliest known flock paper, from Saltfleet Manor, Lincolnshire, had a formalised design with architectural elements and typical 17th-century decorative motifs. Chinoiserie designs were also produced in flock as was the informal asymmetric style of French rococo from the 1740s.

A number of these small-pattern flocks were hung in bedrooms. Elsewhere they were used in parlours and drawing rooms. A popular formal pattern with rococo elements, flocked in red and yellow on a pink background was hung in two first-floor rooms of Sir William Robinson's house at 26 Soho Square, London, in 1759 – 60. It is unlikely that either room hung with flock would have been used for dining as flock papers tended to retain the smell of food, as well as gathering dirt and dust, and were therefore generally considered to be unsuitable in this context. The paper cost 9 shillings per 12-yard piece, and 414 yards were supplied. It is described in Chippendale's itemised bill as 'Crimson Embossed paper'. The term 'embossed', which often appears on trade cards, seems to have been another name for flock because, like embossing, flocking produced a raised surface pattern.

Generally speaking, it seems that the scale of the flock pattern was related to the size of the room, although there are occasional examples of over-sized patterns hung to overwhelming effect in small rooms. A bedroom of the Webb house in Wethersfield, Connecticut, US, was hung with a red flock with a rococo floral pattern in 1781. Hung from ceiling to floor, it has a disturbing effect in such a small, low-ceilinged room. It was supposedly hung in preparation for a visit by George Washington, the first President of the United States, and it may be that the status of the prospective guest had more influence on the choice of paper than did the size of the room itself.

'Mock flock'

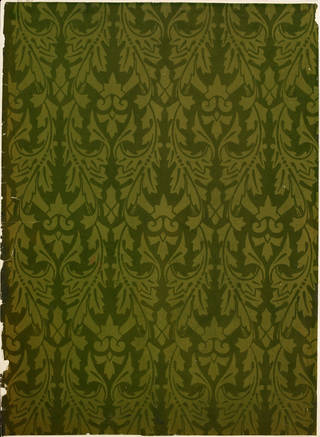

Flocks were generally more expensive than other block-printed papers and most surviving examples come from the houses of the wealthy, although some exceptions are known. For those who could not afford the real thing, 'mock flock' paper was available. These papers copied the styles and motifs of flock papers with solid block-printed areas in a dense black pigment on a 'mosaic' background that gave an effective illusion of true flock.

Such papers were usually considered more appropriate for bedrooms. Although Sir William Robinson had an expensive double flock made for the whole of his first floor at 26 Soho Square, he also had a much cheaper green mock flock hung in one of the second-floor bedrooms at a cost of £3 2 shillings in April and May 1760.

Flocks continued to reflect the changing styles in textile design, and remained in demand through various architectural design styles. Imposing formal patterns were still being designed in the 1820s, alongside lighter informal styles. Flocking was used to embellish designs in every style, from florals to borders with Egyptian motifs and trompe-l'oeil (visual illusion in art) printed 'draperies'.

19th-century flocks were even more convincing as substitutes for cut-velvet than their predecessors, thanks to a further elaboration of the production process whereby the flocked areas were blind-stamped (create a depression) to give an embossed finish.

Red flock has, since the mid-18th century, been a favourite decoration for picture galleries, or for any grand room hung with Old Master paintings. The colour and texture can be a highly effective foil to gilt-framed pictures. In 1748 Thomas Bromwich was paid £45 16 shillings by Sir Matthew Fetherstonhaugh at Uppark, apparently for supplying and hanging a red flock. Artists themselves also subscribed to the general view that red was the best background to pictures. In 1813 the painter Sir Thomas Lawrence P.R.A. wrote of his house at 65 Russell Square:

... thus I suffer a Yellow Paper to remain that I know is hurtful to my Pictures. I should have suffered it in my Painting Room but ... it is now a rich crimson Paper with a Border

The 18th-century English flock papers were renowned for their superior quality. They were exported to Europe, notably France, where papiers d'Angleterre were favoured by wealthy individuals such as Madame de Pompadour, who used English flock papers in her apartments at Versailles and in the Château de Champs-sur-Marne. And like other English wallpapers, flocks were exported to America. Advertisements in the American press from the early 1760s included 'Flock', 'Velvet' or 'Damask': both of the latter terms were used to describe flocked wallpapers. However, they did not suit all customers. Lady Skipwith, an émigrée from England, wrote in 1795 from Virginia to her agent in London: "I am very partial to papers of only one color, or two at most - velvet paper [flock] I think looks too warm for this country".

The luxurious aristocratic associations of flock papers continued into the mid-19th century. Owen Jones, one of the most influential design theorists of the 19th century, produced a number of elaborate papers. A.W.N. Pugin, English architect, designer, artist, and critic, also designed sumptuous flock papers, employing Gothic and medieval motifs. He believed that flock wallpapers were suitable as a medium for designs in the modern Gothic style because they were 'admirable substitutes for ancient hangings'.

Pugin designed all the wallpapers for the Palace of Westminster. A book of samples compiled by Crace & Son, 1851 – 4, shows the variety of styles, and gives details of where each was hung. The simplest two-colour block prints were used in servants' bedrooms, whereas the flock papers (often embellished with gold) were hung in the state and public rooms, such as the Royal Gallery and the Conference Room (now part of the Members' Dining Room), and in the apartments of senior officials.

Pugin made concerted efforts to promote his wallpaper designs to a wider market, and encouraged Crane to advertise his papers in The Builder (an illustrated weekly magazine for architects, engineers and artists) in 1851. However, the majority of his designs, and in particular the large-scale flocks, were entirely unsuitable to a domestic setting, both in scale and because they were thought by his contemporaries to be "too ecclesiastical and traditional in character".

Charles Eastlake's influential Hints on Household Taste, first published in 1868, expressed some strong opinions about wallpaper, and condemned illusionistic and pictorial patterns. However he defended flocks on the grounds that "at ordinary shops [they] are the best in design, because they can represent nothing pictorially". But by the later 19th century flocks were well and truly out of fashion, casually dismissed or roundly condemned by successive writers of guides to interior decoration. Colonel Edis was particularly severe:

I can conceive of nothing more terrible than to be doomed to spend one's life in a house furnished after the fashion of twenty years ago. Dull monotonous walls, on which garish flock papers of the vulgarest possible design, stare one blankly in the face with patches here and there of accumulated dirt and dust ... if the flock paper be red, we had red curtains hung on a gigantic pole, like the mast of a ship ...

Cleanliness had by now become something of an obsession with the Victorians, and lighter colours and washable 'sanitary' papers were supplanting the dark velvety flocks. For those who advised on interior design and household management, flocks had a place only in the library, conventionally a sombrely furnished masculine room, or as a backdrop to pictures since they 'throw up oil paintings to a marvel'.

Dark, gloomy, a hindrance to cleanliness and a hazard to health – the fashion for flock paper was finally in decline. The prejudice against flocks amongst the design pundits did not result in their immediate disappearance from the market though. Designs continued to be produced, including papers by William Morris, Walter Crane and other fashionable designers of so-called 'art wallpapers'. Customers at Cowtan & Son continued to order flocks well into the 1920s, in defiance or in ignorance of these critical injunctions against them. Flocks are still produced today, using rayon flock applied by a flock gun, but the market is more or less limited to restoration projects in historic buildings.