Henry Cole (1808 – 1882) was a prominent civil-servant, educator, inventor and the first director of the V&A. In the 1840s, he was instrumental in reforming the British postal system, helping to set up the Uniform Penny Post which encouraged the sending of seasonal greetings on decorated letterheads and visiting cards. Christmas was a busy time in the Cole household and with unanswered mail piling up, a timesaving solution was needed. Henry turned to his friend, artist John Callcott Horsley to illustrate his idea.

Cole’s diary entry for 17 December 1843 records, “In the Evg Horsley came & brought his design for Christmas Cards”. Horsley's design depicts three generations of the Cole family raising a toast in a central, hand-coloured panel surrounded by a decorative trellis and black and white scenes depicting acts of giving; the twofold message was of celebration and charity. Cole then commissioned a printer to transfer the design onto cards, printing a thousand copies that could be personalised with a hand-written greeting. Horsley himself personalised his card to Cole by drawing a tiny self-portrait in the bottom right corner instead of his signature, along with the date "Xmasse, 1843".

Cole’s Christmas card was also published and offered for sale at a shilling a piece, which was expensive at the time, and the venture was judged a commercial flop. But the 1840s was a period of change, with Prince Albert introducing various German Christmas traditions to the British public, including the decorated Christmas tree.

Cole may have been ahead of his time but the commercialisation of Christmas was on its way, prompted by developments in the publishing industry. More affordable Christmas gift-books and keepsakes were aimed at the growing middle classes, and authors responded to the trend: Charles Dickens wrote Christmas themed stories for Household Words and All the Year Round and published A Christmas Carol in 1843. By the 1870s the Christmas trend was firmly established.

The second Christmas card, designed by artist William Maw Egley (1826 – 1916), came a few years later in 1848 (it was once thought to pre-date Horsley's card, as the date was misread as 1842). The design is noticeably similar to the first card: both show scenes of middle-class festive merriment offset with acts of seasonal charity, and both were printed on single sheets about the size of a ladies' visiting card.

Early Christmas cards were influenced by already popular Valentines and featured ‘paper lace’ (embossed and pierced paper) and layers that opened to reveal flowers and religious symbols including angels watching over sleeping children. The Victorian heyday for Christmas cards (1860 – 1890) was prompted by the new printing processes and techniques that combined colour (chromolithography), metallic inks, fabric appliqué and die-cutting to make elaborately shaped cards.

The 'aesthetic' cards produced in this period were considered tasteful or artfully refined. Sold in bookshops and stationers, they were expensive, at “ninepence the two designs” (from a wrapper in the collection) and aimed at bourgeois customers. Publishers such as Hildesheimer & Co. imported cheaper cards from Germany, before producing the ‘penny basket’ around 1879, which contained around a dozen cards and was sold through tobacconists, drapers and toy shops. The Half Penny Post, introduced in 1894, further boosted Christmas card sales, with the less expensive (both to buy and send) postcard format becoming most popular.

Victorians exchanged, displayed and collected Christmas cards in vast numbers. In the process they established the now familiar iconography of Christmas. This period saw the debut of many of the meaningful symbols and decorative devices that we associate with the festive season: winter scenes of robins, holly, evergreens, country churches and snowy landscapes; along with indoor scenes of seasonal rituals and gift giving, from decorating trees and Christmas dinner, to Santa Claus, children’s games, pantomime characters and Christmas crackers – another Victorian invention.

Renowned illustrators produced designs for Christmas cards: Linnie Watts adapted her poignant paintings of children (signed with her joined-up LW monogram), while the artist Harry Payne, celebrated for his accurate depictions of military uniforms, turned sentimental portrayals of soldiers into Christmas cards connecting families and friends across the British empire.

Such heartfelt communications were ready-made keepsakes and collecting Christmas cards became a middle class passion. In his book The History of the Christmas Card (1954), collector George Buday suggested that, “the Christmas card from its beginning was more closely associated in the minds of the senders with the social aspect – the festivities connected with Christmas than with the religious function of the season”, and describes the Victorian craze for Christmas cards as “the emergence of a form of popular art”.

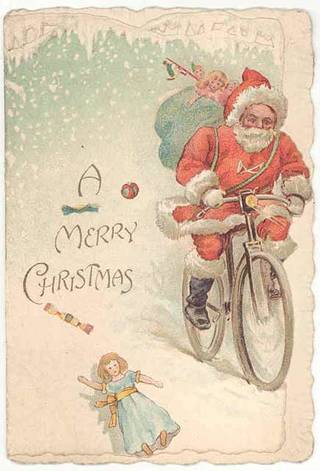

Buday donated his own extensive collection of cards to the Museum, making it possible to trace evolving traditions through decades of examples. By the turn of the century, Father Christmas – good Victorian that he was – was moving with the times: one design shows him hurtling through the snow atop a bicycle – relatively new technology in the late 19th century. The message on the inside of the card reads: "Here's good old father Christmas, on his bicycle astride, may he bring you lots of presents, and a merry Christmas-tide".

What started off as a pragmatic gesture by Henry Cole has grown into a multi-million pound retail phenomenon, with around a billion Christmas cards bought in the UK each year. Cole still makes the news though; when one of his first cards was auctioned in 2013 it sold for £22,000. Every year we revive Cole's entrepreneurial spirit by launching exclusive card ranges in the V&A Shop inspired by favourite designs from this historic collection.

Find out more about our greetings card collection in Explore the Collections.