Fashion

Features

-

Read

100 years of fashion photography

Discover the key trends in fashion photography over the last 100 years

-

Read

The bottom line: underwear revealed

The bottom line: underwear revealedTake a peek at our underwear collection

-

Watch

Fashion unpicked: The 'Bar' suit by Christian Dior

Watch dressmaking expert and V&A volunteer, Sue Clark, as she examines Christian Dior's 'Bar' suit

-

Read

Art Deco fashion

From Jeanne Lanvin's haute couture to the bold geometric jewellery of Raymond Templier, discover the Art Deco aesthetic in the fashions of the 1920s and 1930s

-

Watch

BLITZ magazine and the tale of 22 denim jackets

Discover era-defining style magazine BLITZ and their designer denim jacket project

-

Read

Five iconic Giorgio Armani looks from the V&A collections

Five iconic Giorgio Armani looks from the V&A collectionsDiscover five key ensembles from iconic Italian fashion designer Giorgio Armani

-

Watch

The future of fashion

As the fashion industry continues to plunder the earth's resources, innovators are striving to find alternative production processes

-

Watch

X-raying the Fashion collection

Find out how we're shedding new light on our Fashion collections through the illuminating mode of X-ray

-

Read

The fashion show

Discover the origins of the catwalk show

-

Watch

The design process: interviews with Agent Provocateur, FiFi Chachnil and La Perla

From creation to catwalk - discover the design process of three leading fashion brands

-

Interact

X-raying Balenciaga

Discover the hidden interior structures of iconic garments by Cristóbal Balenciaga, revealed through beautiful X-rays

-

Watch

The 'Babydoll' slip by Carine Gilson

Lingerie designer, Carine Gilson discusses the design process behind the 'Babydoll' slip featured in the exhibition

-

Watch

Designing for the bride

Gareth Pugh, Pam Hogg and Philip Treacy discuss bespoke bridal commissions

-

Read

Ocean liner fashion: a socialite's guide

Find out why dressing for an ocean voyage was "the acid test of true chic"

-

View

An exclusive pattern by Katie Jones, crochet and knitwear designer – meet, make and do

An exclusive pattern by Katie Jones, crochet and knitwear designer – meet, make and doMeet Katie Jones – technicolour knitwear and crochet designer passionate about her ethical craft

-

Watch

Balenciaga's sequinned evening coat

Recreating the beautiful hot-pink beading and sequin work of Balenciaga's 1967 evening coat.

-

Watch

Secrets of Balenciaga's construction

Animated dress patterns show how three of Balenciaga's iconic designs were constructed, revealing his mastery of pattern cutting, draping and manipulation of fabrics.

-

Read

How Arts and Crafts influenced fashion

How did the ideas of the Arts and Crafts movement influence the design and manufacture of clothes, accessories and jewellery?

-

Interact

Revealing hidden structures through x-rays

Discover the internal structures of a hat, stays, and a hood - three historic objects from the exhibition, Fashioned from Nature

-

Read

Women's tie-on pockets

Find out how the development of the humble pocket offered independence and security for women

-

Watch

Fashioned from the animal kingdom

Working with colleagues at the Natural History Museum, London, we explore some of the materials used to create fashion that are drawn from the natural world

-

Read

Fashion inspired by the natural world

Discover more about how nature has provided a rich source of inspiration for fashion over the centuries

-

Watch

Making an entrance – ocean liner style

The glamour of first-class travel is brought to life for the exhibition Ocean Liners: Speed and Style

-

Read

Knitted eveningwear

Discover how knitted fabrics have created glamorous evening dresses through the 20th century and beyond

-

Read

Pollution: the dark side of fashion

Despite using the natural world as a source book, the fashion industry's processes and practices harm environments, ecosystems and human communities globally

-

Watch

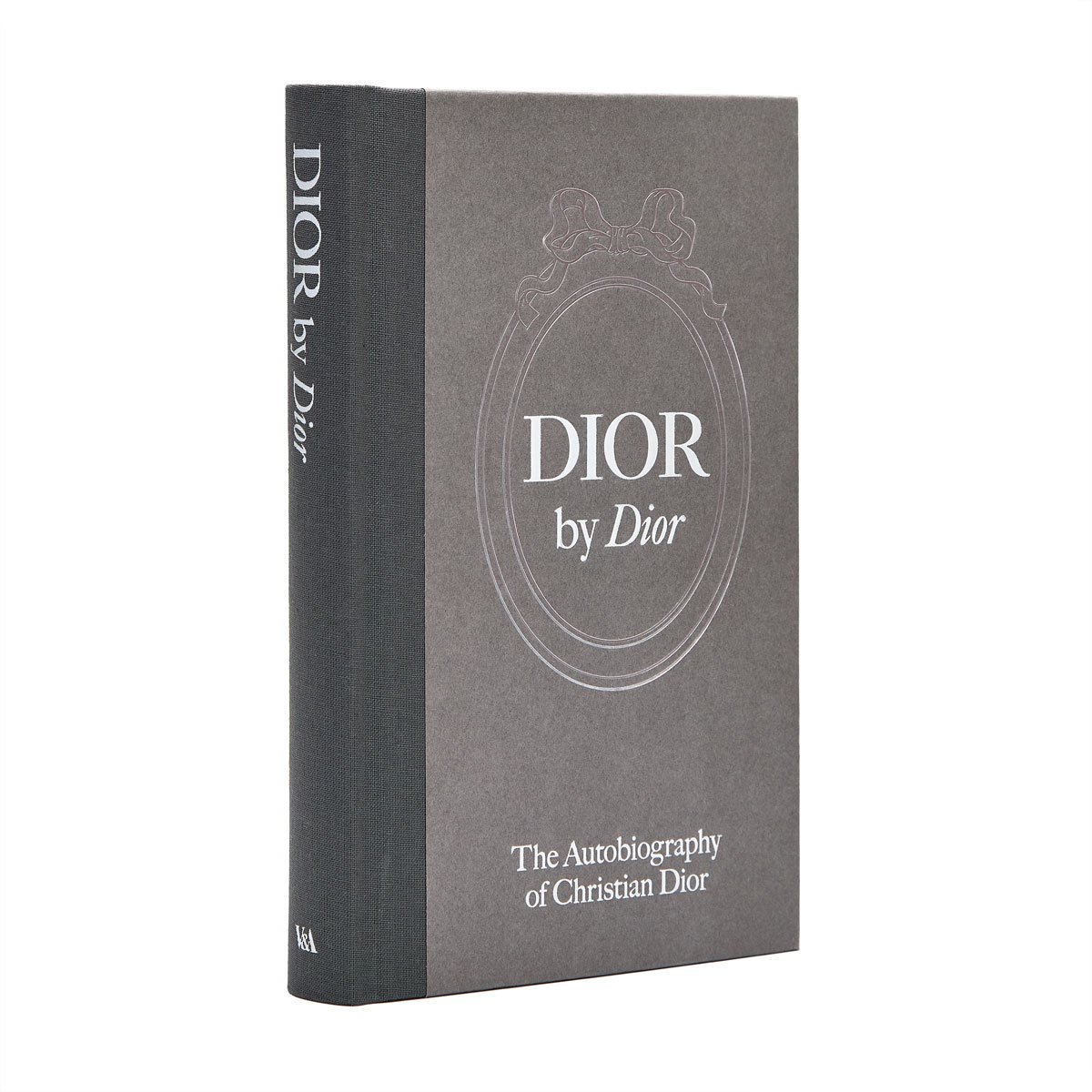

Stephen Jones and Dior

Milliner, Stephen Jones, discusses working alongside Dior to create exquisite hats and headpieces to complement their designs

-

Watch

Meet Jean Dawnay, Dior's English rose

Jean Dawnay's daughter, Katya Galitzine, discusses her Mother's modelling career during Dior's golden age

-

Watch

BodyMap: shaping 1980s fashion

Discover how influential British fashion label BodyMap shaped the 1980s catwalk scene

-

View

Dior in Britain

A confirmed Anglophile, Christian Dior associated his many visits to Britain with "a sensation of happiness and great personal freedom"

-

Listen

Modelling for a legend – Svetlana Lloyd on Dior

Listen to 1950s Dior mannequin Svetlana Lloyd discussing working for the house

-

Read

Lolita fashion: Japanese street style

Sweet, punk or gothic?

-

Make

Sew your own: Mary Quant 'Georgie' dress

Get creative with our free downloadable sewing pattern!

-

Watch

20 years of Fashion in Motion

Fashion in Motion has brought free catwalk shows to the public for the past 20 years

-

Watch

Barbara Nessim: an artful life

Meet American artist, fashion designer and computer art pioneer, Barbara Nessim

-

Read

Madeleine Vionnet – an introduction

Couturier Madeleine Vionnet changed the shape of women's fashion with her revolutionary 'bias-cutting' technique

-

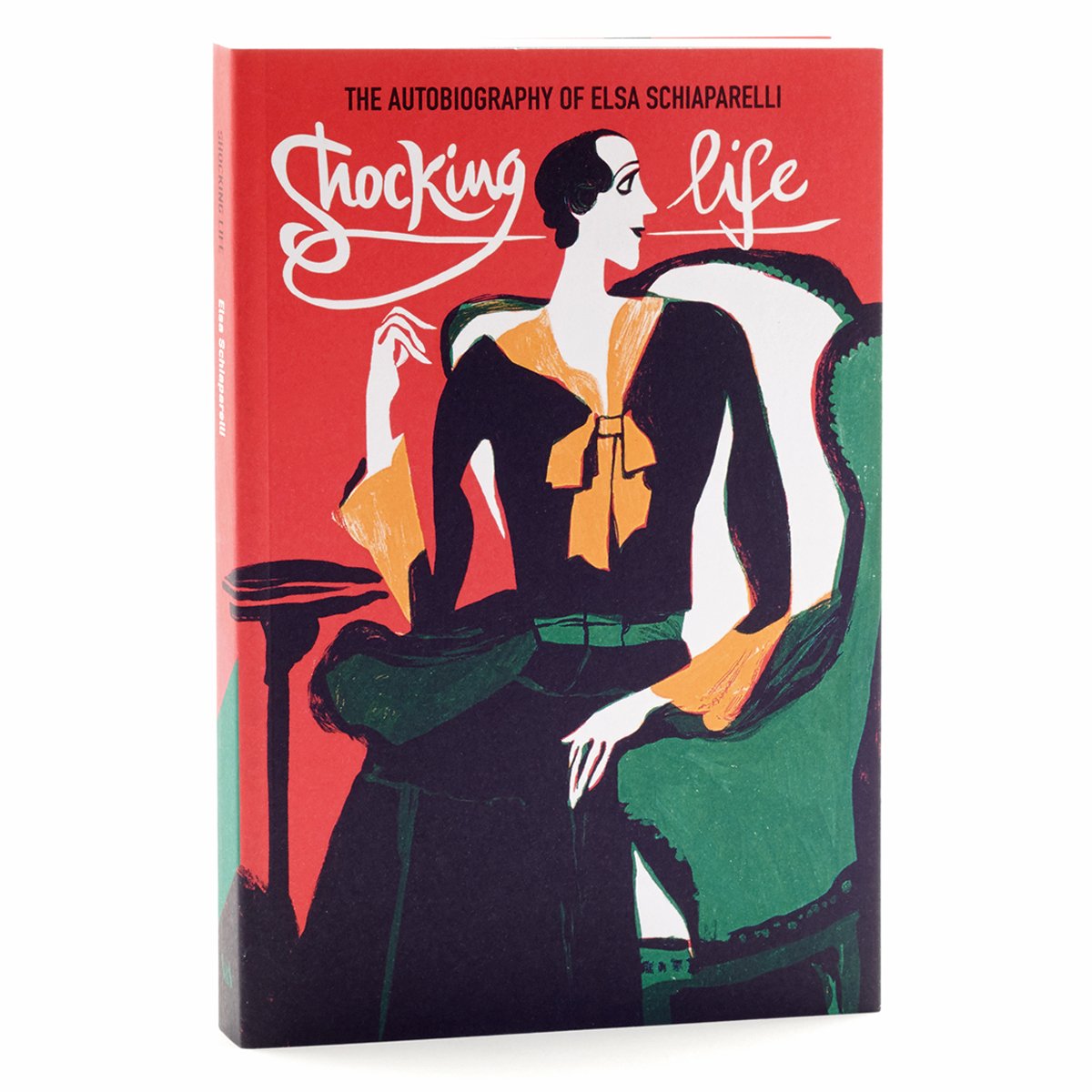

Watch

Introducing Elsa Schiaparelli

Shocking, subversive, surreal – meet Elsa Schiaparelli

-

Read

'King of Fashion' by Paul Poiret

Fashion designer Paul Poiret describes his debut as a couturier in this extract from his 1931 autobiography

-

Read

'From A to Biba' by Barbara Hulanicki

Discover the humble beginnings of a legendary fashion label

-

Read

'With Tongue in Chic' by Ernestine Carter

Fashion journalist Ernestine Carter recalls her first glimpse of Christian Dior's 'New Look' in this extract from her autobiography

-

Read

'Silver and Gold' by Norman Hartnell

Couturier Norman Hartnell describes the pinnacle of his career: designing the Coronation dress for Queen Elizabeth II

-

Watch

Making bags

Take a look at the complex process of making bags

-

Watch

The Infinity Dress and Omniverse Sculpture

A voluminous kinetic 'halo' hovers around a magical feathered dress

-

Watch

Yohji Yamamoto: Poet of Black

Hear from enigmatic fashion designer Yohji Yamamoto as he talks about his career and design values

-

Watch

Fashion design: Rahemur Rahman

Sustainable, ethical fashion, "for people who dream in colour"

-

Read

A brief history of men's underwear

A brief history of men's underwear

From ruffle-fronted shirts, to Y-fronts, jock-straps and Calvin Kleins, explore the hidden history of men's underwear

-

View

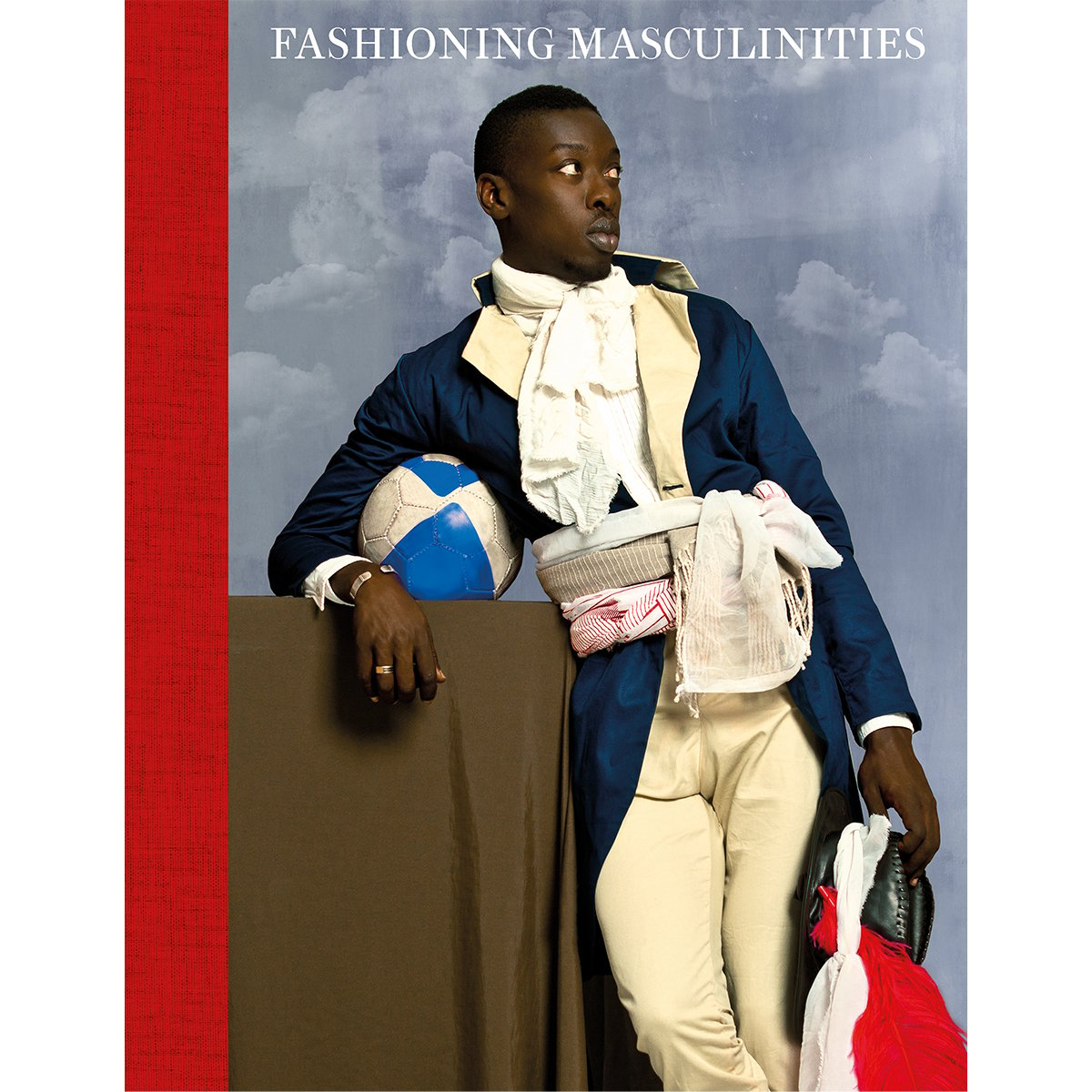

Inside the Fashioning Masculinities exhibition

Take a look inside our first major exhibition to celebrate the art of menswear

-

Watch

Fashion design: Edward Crutchley

Sumptuous and subversive fashions which disregard gender

-

Watch

Fashion design: Samuel Ross / A-COLD-WALL*

Clothing as "armour for the now", or architecture for the body

-

Read

In the pink: colour in menswear

Discover the dazzling spectrum of colours in menswear throughout history

-

Watch

Fashion design: Priya Ahluwalia

"One of the most important outfits in a man's wardrobe is a tracksuit"

-

Read

A life through clothes: Professor Lalage Bown, OBE

Take a look inside the wardrobe of Professor Lalage Bown, OBE

-

Read

Family, photography, memories: Africa Fashion

Find out about the personal stories and unique fashion histories from individuals across the continent

-

Read

'My Years and Seasons' by Pierre Balmain

Legendary couturier Pierre Balmain recalls his fledgeling fashion show in this extract from his autobiography

-

Watch

Nigeria's first fashion designer: Shade Thomas-Fahm

Meet iconic fashion designer Shade Thomas-Fahm

-

Read

Tortoiseshell combs from Jamaica

This Intriguing set of tortoiseshell objects reveal a colonial history

-

Watch

Conserving an 18th-century portrait and waistcoat

Follow the conservation of two uniquely connected objects – a rare double acquisition for the museum

-

Watch

Nisha Kanabar: Industrie Africa

Meet Nisha Kanabar, founder and CEO of Industrie Africa

-

Watch

Magician of the desert: Alphadi

Meet Alphadi – world renowned fashion designer drawing upon histories and cultures from across the continent

-

Watch

Fashion Unpicked: couture ensemble by Imane Ayissi

Join Senior Curator Christine Checinska as she examines this striking fuchsia ensemble

-

Read

Fashion in Virginia Woolf's 'Orlando'

Curator Rosalind McKever explores fashion, gender and identity in Virgina Woolf’s novel 'Orlando'.

-

Watch

Fashion Unpicked: YSL couture evening dress and shoes

Discover a dazzling 1960s evening dress by Yves Saint Laurent and matching shoes by Roger Vivier

-

Watch

100 years of fashionable womenswear

Explore three unique dresses spanning 100 years of fashion history

-

Read

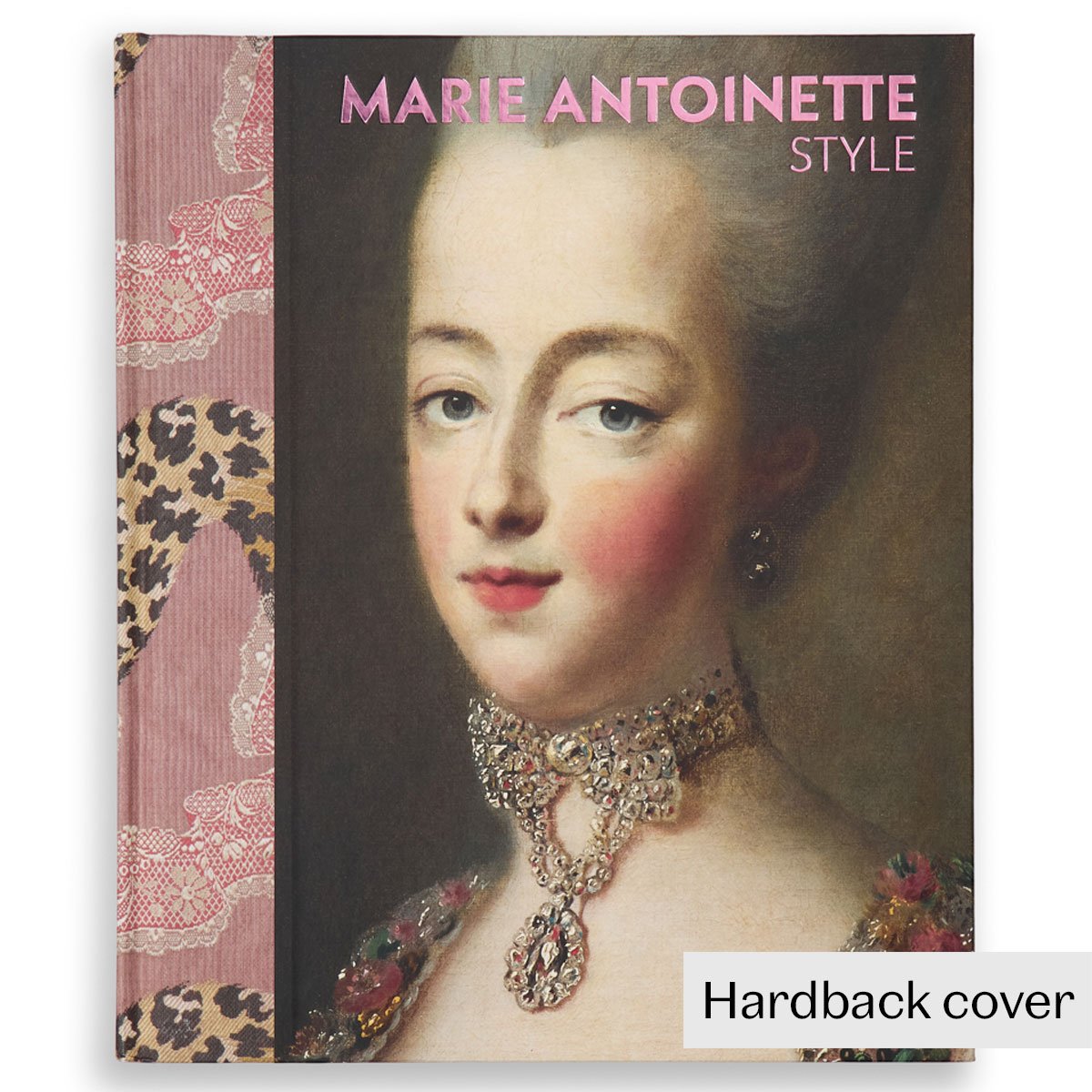

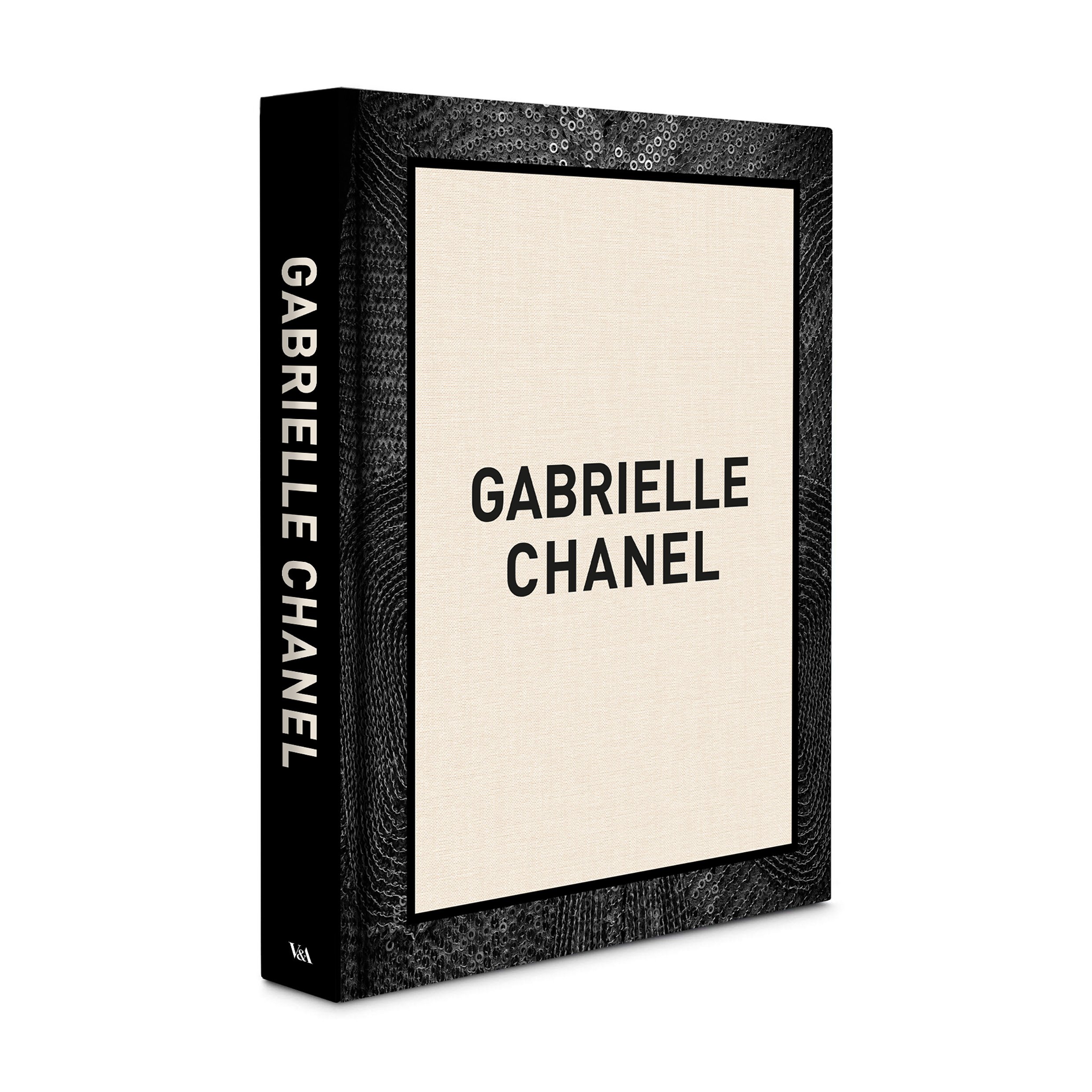

What makes CHANEL so iconic?

Explore the evolution of Gabrielle Chanel's design philosophy through her most enduring and recognisable pieces

-

Watch

Fashion unpicked: CHANEL tweed suit worn by Lauren Bacall

See the exquisite hand-sewn detailing of a suit made for a star

-

Read

Gabrielle Chanel: dressing the modern woman

How did the designer change the face of women's fashion?

-

Read

Gabrielle Chanel in Britain

Discover how the designer was inspired by Britain

-

Watch

Barbie vs Sindy: who wins the fashion race?

Meet our favourite Barbie and Sindy dolls

-

Watch

Fashion Unpicked: CHANEL sequin trouser suit worn by Diana Vreeland

Take a close-up look at the glamorous design

-

Read

Top 10 Naomi Campbell looks

Top 10 Naomi Campbell looksCould she wear anything more iconic?

-

Read

The groundbreaking Black models who changed fashion

The groundbreaking Black models who changed fashionFind out about the trailblazing women who paved the way

-

Listen

Naomi Campbell's ultimate catwalk mix

Naomi Campbell's ultimate catwalk mixListen to the supermodel's specially curated playlist

-

Watch

Unboxing Naomi Campbell's platform shoes

Unboxing Naomi Campbell's platform shoesTake a peek, inside and out

-

Watch

Unboxing a couture Versace dress worn by Naomi Campbell

See the spectacular leather dress up close

-

Watch

Victorian fashion history: 1890s

Victorian fashion history: 1890sVictorian fashion is not what you think...

-

Read

Packing objects for a new home: ASMR

Packing objects for a new home: ASMRHow do you move over 250,000 museum objects from one side of London to the other?

-

Visit

V&A trail: Contemporary fashion

V&A trail: Contemporary fashionTake a self-guided trail around V&A South Kensington to discover some highlights from our 21st-century fashion collections.

-

Watch

Adaptive fashion: 1960s wedding dress and shoes

Adaptive fashion: 1960s wedding dress and shoesA stunning example of 1960s adaptive bridal fashion

-

Watch

Tatreez: the ancient art of Palestinian embroidery

Tatreez: the ancient art of Palestinian embroideryDiscover six incredible examples of embroidered Palestinian fashion.

-

Read

The art of fashion plates: a hidden history of three pioneering women

The art of fashion plates: a hidden history of three pioneering womenDiscover three French sisters who, in a pre-photographic era, pioneered the way fashion was depicted in mass media

-

Watch

Conserving a fragile 200-year-old fan from the era of Marie Antoinette

Conserving a fragile 200-year-old fan from the era of Marie AntoinetteJoin Senior Paper Conservator Susan Catcher as she conserves a fragile 200-year-old fan from the era of Marie Antoinette.

Collection highlights

-

Hat, designed by Simone Mirman, about 1955, London, EnglandV&A East StorehouseView by appointment

Hat, designed by Simone Mirman, about 1955, London, EnglandV&A East StorehouseView by appointment -

Evening dress, designed by Cristóbal Balenciaga, 1954, Paris, FranceV&A East StorehouseView by appointment

Evening dress, designed by Cristóbal Balenciaga, 1954, Paris, FranceV&A East StorehouseView by appointment -

Man's suit, designed by Mr Fish, manufactured by Hexter, about 1968, London, EnglandV&A South KensingtonNot on display

Man's suit, designed by Mr Fish, manufactured by Hexter, about 1968, London, EnglandV&A South KensingtonNot on display -

Pair of shoes, 1550 – 1070 BC, EgyptV&A East StorehouseView by appointment

Pair of shoes, 1550 – 1070 BC, EgyptV&A East StorehouseView by appointment -

Mantua, 1755 – 60, EnglandV&A East StorehouseView by appointment

Mantua, 1755 – 60, EnglandV&A East StorehouseView by appointment -

Plato's Atlantis, dress, designed by Alexander McQueen, 2010, London, EnglandV&A South KensingtonNot on display

Plato's Atlantis, dress, designed by Alexander McQueen, 2010, London, EnglandV&A South KensingtonNot on display -

Man's ensemble, designed by Stella Jean, Spring/Summer 2014, Italy and Burkina Faso. Museum no. T.21:1 to 5-2014.V&A South KensingtonNot on display

Man's ensemble, designed by Stella Jean, Spring/Summer 2014, Italy and Burkina Faso. Museum no. T.21:1 to 5-2014.V&A South KensingtonNot on display