The V&A has in its collections many books, manuscripts, prints, paintings and other objects relating to Dickens. The largest single group of Dickens material came to the museum in 1876 when the author's friend and first biographer John Forster (1812 – 76) bequeathed his entire library (over 18,000 books) as well as his small collection of paintings, prints and drawings to the museum.

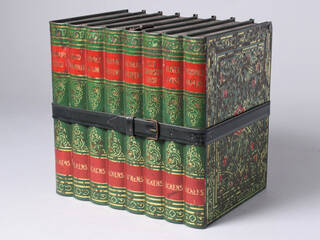

The Forster Collection, now in the National Art Library at the V&A, includes the manuscripts for most of Dickens' major novels, as well as autograph letters, working notes, printers' proofs, first editions and original drawings. Collectively these provide a fascinating picture of Dickens' output: his ideas and methods, the development of his plots and characters, and his skill as a craftsman and stylist.

The Dickens manuscripts

Dickens began to keep the manuscripts of his novels after about 1840. The manuscript of Oliver Twist, a novel first published in monthly instalments in the literary magazine Bentley's Miscellany in 1837 – 39, was left with the publisher. About two thirds of the original manuscript (22 chapters) resurfaced when Bentley's premises were cleared out in 1870 and were subsequently bought by Forster at a Sotheby's auction on 23 July of that year, and later bequeathed to the V&A. Some stray leaves are found in other collections, such as the Charles Dickens Museum in London.

When Dickens died in 1870, Forster inherited the complete manuscripts of most of his other works, including The Old Curiosity Shop (1840 – 41); Sketches of Young Couples (1840); Barnaby Rudge (1841); American Notes (1842); Martin Chuzzlewit (1843 – 44); The Chimes (1844), Some dealings with the firm of Dombey and Son (1846 – 48); Travelling Letters (1846); David Copperfield (1849 – 50); A Child's History of England (1851 – 53); Bleak House (1852 – 53); Hard Times (1854); Little Dorrit (1855 – 57); A Tale of Two Cities (1859) and The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870).

The manuscripts of his other Christmas stories, A Christmas Carol (1844), The Cricket on the Hearth (1845) and The Battle of Life (1846) can be found in the Morgan Library in New York, as can his novel Our Mutual Friend (1865), which was originally given by Dickens to the journalist Eneas Sweetland Dallas (1828 – 79) in January 1866 in thanks for his very favourable review in The Times.

Dickens gave the manuscript of Great Expectations (1860 – 61) to his friend the poet Chauncy Hare Townshend (1798 – 1868), to whom he had dedicated the novel. Townshend subsequently left it to the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, where it is held today. Fragments of The Pickwick Papers (1836 – 37) are in the New York Public Library and elsewhere, whilst the British Library holds the manuscript for Nicholas Nickleby (1838 – 39).

Illustrations for Dickens' novels

Most of Dickens' novels were first published in a serial format, coming out monthly or weekly. Some of the most outstanding illustrators and artists of the day were recruited to provide images to accompany the text, often producing illustrations at short notice and with little information for forthcoming chapters.

Dickens' first writing commission was to provide text for prints by Robert Seymour (1800 – 36), who created the first set of images for what became The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1837).

After Seymour's tragic suicide, the set was developed by the illustrator Hablot Knight Browne (1815 – 82), who adopted the pseudonym 'Phiz' to echo Dickens' own pseudonym 'Boz'. Phiz went on to provide illustrations for ten of Dickens' novels and collaborated with him as one of his main illustrators for over two decades. His output includes sets of images for Martin Chuzzlewit (1843 – 44), David Copperfield (1849 – 50) and A Tale of Two Cities (1859).

Dickens' other long-term collaborator for illustration was George Cruikshank (1792 – 1878). We hold drawings, proofs and sets of images for Sketches by Boz (1836), the Mudfog Papers that appeared in Bentley's Miscellany in 1837, and Oliver Twist, including the draft cover design of the 1846 monthly edition.

The artwork, drafts and complete illustrations by Luke Fildes (1844 – 1927) for Dickens' last – and unfinished – novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), are also in the museum's collections.

By the time of his death in 1870, Dickens had acquired the kind of celebrity that film stars might have today. As a result of this fame, images of the writer were mass produced as photographs and prints. His remains were buried in Westminster Abbey. Forster commissioned a watercolour by Sir Luke Fildes, showing the writer's gravestone opposite a memorial to the English playwright William Shakespeare, placing him in his lineage.

Explore Charles Dickens in the V&A Collections

Charles Dickens material can be found in Explore the Collections and the National Art Library.

Research projects

Deciphering Dickens – developing and trialing ways in which Dickens' creative process can be opened out online.

Immersive Dickens – bringing an original Charles Dickens manuscript alive through an innovative mix of technology, performance and curatorial practice.

The Dickens Code – Dickens' letters from the V&A Collection featuring in an online exhibition focussed on his practice of shorthand writing.