Donatello (about 1386 – 1466) created some of the most significant sculptures of the biblical hero David to come out of the Renaissance. While Michelangelo's monumental marble 'David' is perhaps better known today, Donatello's iconic bronze was the first free-standing male nude in this luxurious material since antiquity, doubtless inspiring Michelangelo among other masters.

The Renaissance master Donatello returned to the subject of David at least three times, from the striking early marble to a later David in the same material completed by others after his death, as well as his famous bronze. Each of these powerful sculptures embodies both religious and political meanings.

The Old Testament (1 Samuel 17) tells how the young shepherd and future king, David, offered to fight the Philistine giant Goliath, who was threatening his native Israel. Having refused the offer of armour by the Israelite King Saul, and equipped only with a sling and stones, the gallant youth defeated his enemy with a single shot. In each of Donatello's sculptures, the victorious David stands triumphantly astride the head of the bearded Goliath, that he had severed with the giant's own sword.

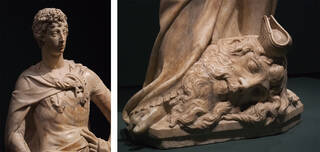

Donatello's first marble David, carved when the sculptor was in his early twenties, was commissioned in 1408 by the Opera del Duomo, to stand high on a buttress of Florence Cathedral. It demonstrates a traditional gothic influence alongside Donatello's clear knowledge of the sculpture of ancient Greece and Rome, seen in David's youthful head and in the hint of a classical contrapposto stance (with the weight carried on his left leg). Donatello's superb carving skills can be seen in the details of the tightly warn garment, stitched at the side and knotted on the chest of the young David. Goliath's head, with its wiry hair and beard, still has the lethal stone embedded in its forehead, and the sling (minus its straps) is loaded with another missile in readiness.

Donatello paid particular attention to how his sculptures would be viewed, but despite David's elongated body, the finished statue would have been too small to be seen successfully when high up on the Cathedral. In 1416, it was taken over by the government, and Donatello was paid to make adjustments for its move to the Palazzo della Signoria (now Palazzo Vecchio), or town hall. It is unclear exactly what work he undertook, but we know that it was placed in the Sala dell'Orologio (room of the clock), where it soon became a symbol of good government. By 1510 an inscription was added to indicate that with God's protection it was possible to defeat even the most terrible of foes.

This combination of both religious and political meaning seems to have appealed to Cosimo de' Medici, the head of the influential banking family. He most likely commissioned the bronze David from Donatello in about 1435 – 40 or later. By 1469 it was set up in Cosimo's new palace (now the Medici Riccardi Palace) – built by Donatello's one-time partner Michelozzo di Bartolomeo. Passers-by could glimpse this extraordinary sculpture, placed high on a column in the centre of the courtyard. Bronze was the most expensive of the sculptural materials, and was associated with eternity and authority, linked with the classical past. For a private family to commission such a work signalled not only their wealth, but potentially also their claim to power.

In the nearby garden stood another bronze by Donatello depicting a tyrant slayer, Judith and Holofernes. Together the two sculptures could be read as a warning to all who saw them, not to challenge the Medici's unique position as leading citizens within the Florentine republic, while promoting them as protectors and champions of good government. When the Medici were expelled in 1494, both sculptures were taken over by the government. Casts of both David and Judith and Holofernes can be seen in the V&A's Cast Collection.

The sensual treatment of David's bronze nakedness has led some scholars to consider it a homoerotic image. David is dressed only in a hat and boots, while the feather of Goliath's helmet seems to caress the youth's inner thigh. However, the sculpture is transformed when viewed from some distance below, as it was originally seen, with the youth's coy stance becoming a confident stand. David's nakedness could be read as suggestive of his refusal of armour, choosing to face his adversary with only the protection of God, as in the biblical account. But it was undoubtedly a direct reference to antique sculpture, indicating both the intellect of its owners and Donatello's place as an innovator. This evocative sculpture may have been designed to encompass layers of meaning for those who viewed it.

Another David by Donatello is the marble that once belonged to the Martelli family, allies of the Medici, which was said to have been gifted to the family by the sculptor. The statue appears in a painting of Ugolino Martelli by Bronzino painted in 1536 – 37. In 1489, it was described as being set into a wall in their palace, but with no attribution to Donatello. Once again, the giant-slayer, this time fully-clothed, stands astride Goliath's head, one arm resting on his hip. Although begun by Donatello, the surface has been significantly reworked by others.

Donatello's sculptures of David inspired others that followed. Andrea del Verrocchio created another partially gilt bronze of the biblical hero for the Medici family in about 1465, which was sold by them to the State in 1476. Small-scale Davids have been attributed to Donatello's assistant, Bartolomeo Bellano, which also inspired the later sculptor, Severo da Ravenna, to create his own variation in about 1520. Most famously, the unusual nakedness of Donatello's bronze must have had an impact on Michelangelo when carving his 17-foot-tall marble David in 1501 – 04. Like Donatello's original marble, it too was intended for the Cathedral buttress, but this time the 'giant', as it was known, was considered too heavy, and instead replaced Donatello's Judith and Holofernes at the entrance to the Palazzo della Signoria, in some senses continuing Donatello's legacy.

Find out more about Sculpture at the V&A. Explore our Renaissance Collection and Cast Collection.