Assistant Curator, Janet Birkett, explores V&A Theatre and Performance Collections for examples of pigs in British theatre.

Readers of The Stage newspaper will be familiar with Hamlet, the cartoon pig created by Harry Venning. Hamlet is an actor with strong opinions but only a modest talent, and spends more time in the bar than he does in work. However, opportunities for porcine stardom do exist and a search through the V&A Theatre and Performance collections reveals a surprising number of works containing suitable roles.

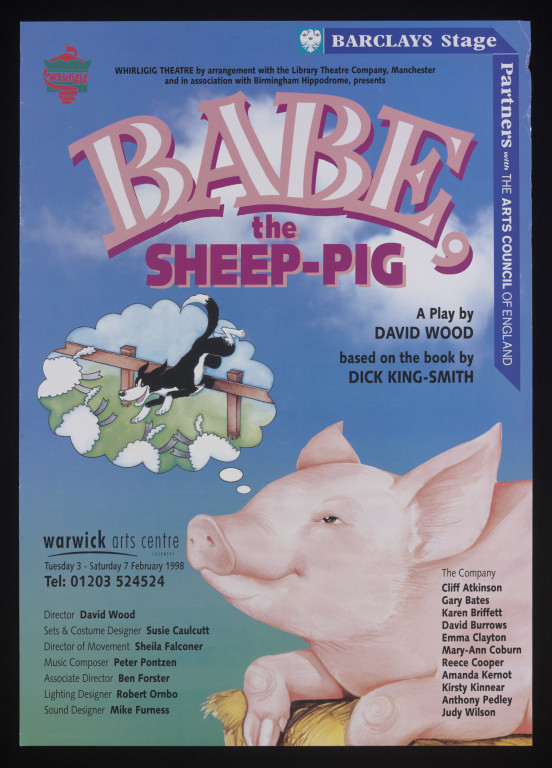

Babe, hero of Dick King-Smith’s novel, The Sheep-Pig, has been brought to the stage in a dramatization by David Wood. Pigs sing in Richard Blackford’s chamber opera, The Pig Organ, and dance in the ballet, The Tales of Beatrix Potter. Adaptations of Orwell’s Animal Farm show a less admirable side of swinish nature, but theatrical pigs are usually sympathetic characters. Often threatened with the oven, they triumph against the odds. Betty the pig ended up on a banquet table in the 1984 Alan Bennett film A Private Function, but in the 2011 musical version, Betty Blue Eyes, she gets a reprieve. In the London premiere Betty became an animatronic model which delighted audiences by singing with the voice of Kylie Minogue during the curtain call.

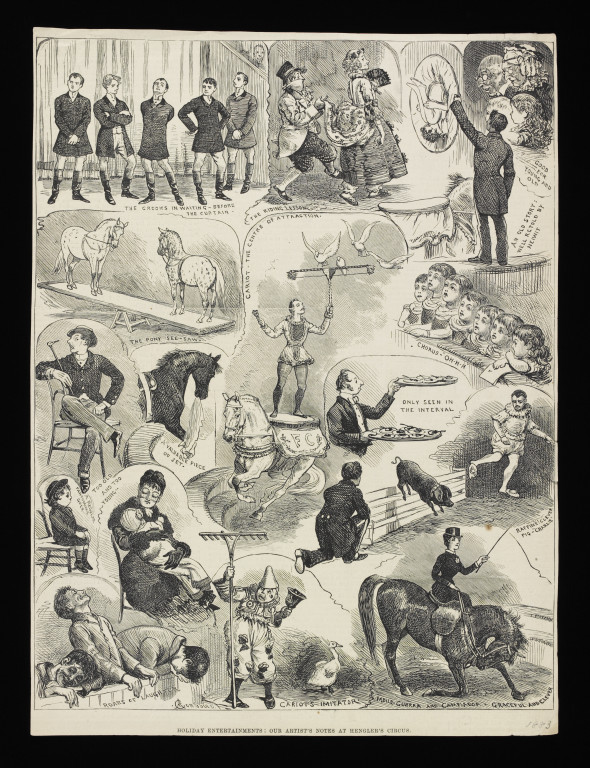

Practicality, and hygiene, make it unlikely that live pigs will grace the stage today, though some did feature in a 1988 open-air promenade production of As You Like It in Lancaster, and made the news when they needed sun cream. In previous centuries, untroubled by animal welfare regulations, things were different. Hengler’s Circus, where the London Palladium stands today, presented entertainments in the 1870s and 1880s, and the 1882 Christmas show featured Raffin the Clown with his Clever Pig, Charlie. Raffin trained pigs to jump through hoops and leap over obstacles.

Athletic Charlie does not seem quite so clever when compared to pigs 100 years earlier. In 1783 Samuel Bisset, an animal trainer, introduced Dublin audiences to the Learned Pig, who could spell out words and do arithmetic by picking out letters and numbers written on cards. He could also, according to his publicity, tell the time, distinguish colours and read minds. After Bisset’s death the pig acquired a new manager and was taken on tour, reaching London in 1785, where he appeared at a house in Charing Cross and later with a circus at Sadler’s Wells. Further tours followed in 1786 and 1787. It is no exaggeration to say that the pig was a sensation. Writers speculated on his training and intelligence and crowds flocked to see him. An anonymous ‘officer of the Royal Navy’ produced the star’s biography, having, in conversation with the pig, learnt that the animal was possessed of a soul that had occupied many bodies down the ages. The book has earned itself a place in Shakespeare authorship studies as one of the pig’s previous incarnations was a holder of horses outside ‘the playhouse’, who claimed to have written five of Shakespeare’s plays.

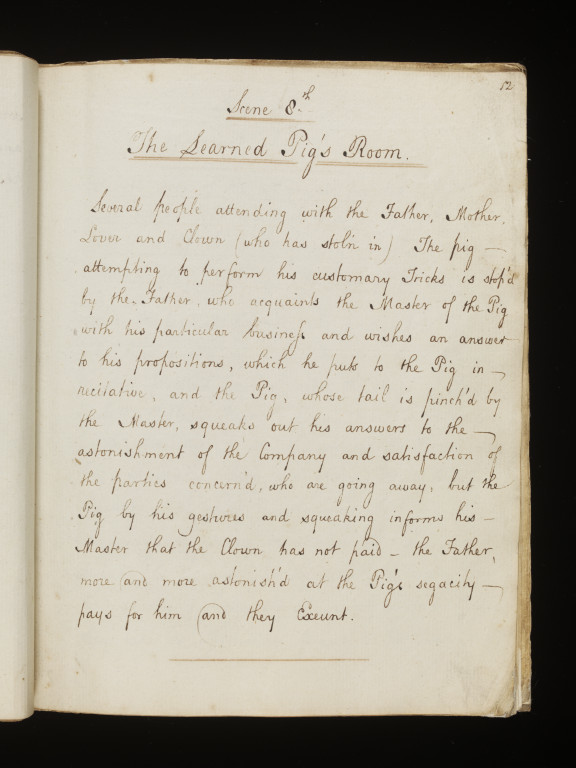

The public’s fascination with the Learned Pig gave plenty of scope for satire and comedy. The Theatre and Performance department holds a manuscript synopsis of the 1785 Covent Garden pantomime Omai, and this contains a scene at the Learned Pig’s House in Charing Cross. Omai, inspired by the published account of Captain Cook’s 1776-80 voyage, was a fantastical and nonsensical piece, full of songs and spectacular scenery, and no complete text survives. The V&A’s manuscript, which belonged to the composer William Shield, is an early version of the plot and the pig may have been omitted from the eventual production, losing a good topical joke in the process. Polynesian islander Omai has visited London and eloped with the heroine. In Shield’s manuscript her family take advice from the pig, played by an actor, who answers questions by squeaking. The onstage spectators are impressed but the audience is aware that the pig’s owner pinches the animal’s tail to elicit appropriate responses. Having mocked the credulous who believe in the pig’s abilities, there is a classic undermining of expectations. As the family prepare to leave, the pig realises that they haven’t paid and alerts his master, thus proving his intelligence.

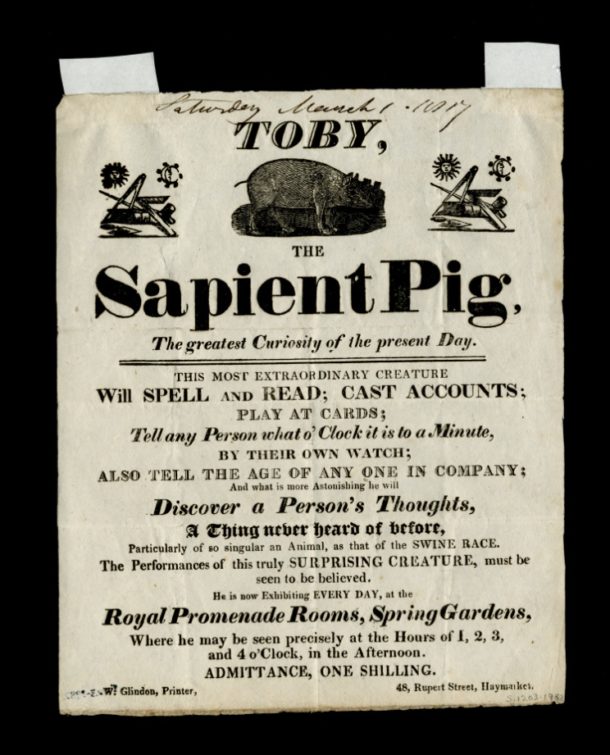

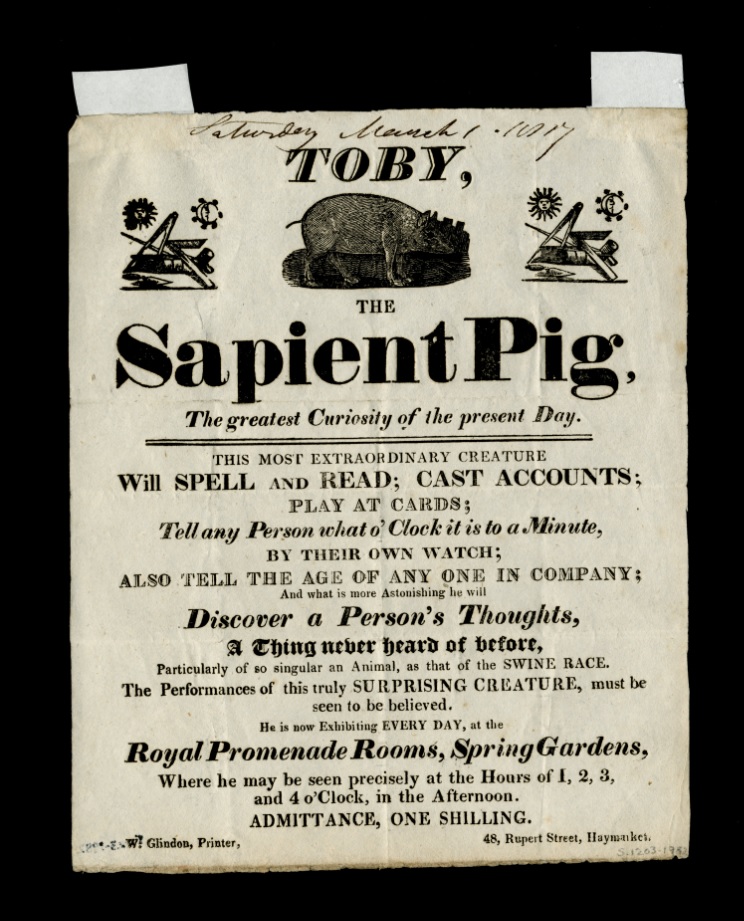

The success of the Learned Pig prompted other animal trainers to try their luck and the early 19th century saw a number of porcine geniuses. The most significant of these was Toby the Sapient Pig, who first appeared in London in 1817, at Spring Gardens (Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens). A handbill lists his many skills.

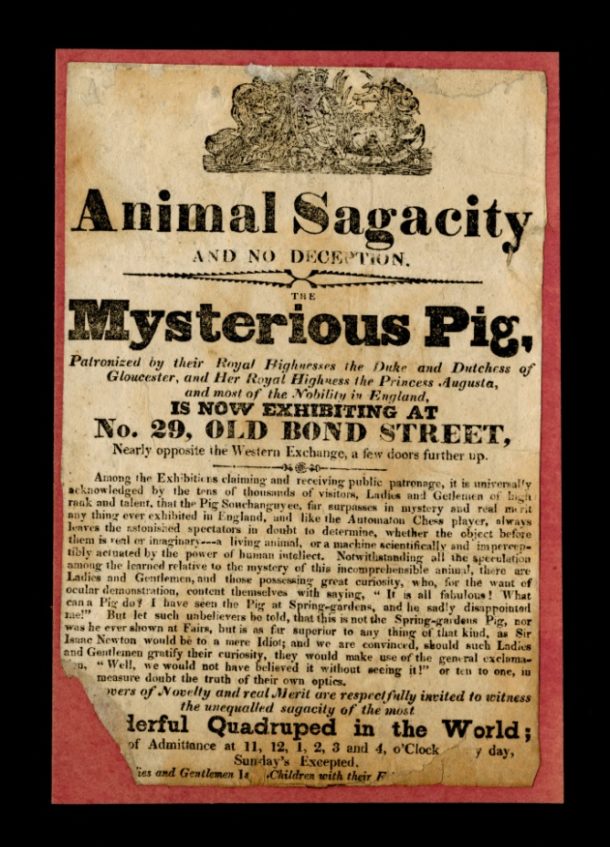

Advertisements for a rival, billed as Souchanguyee, the Mysterious Pig, belittled Toby (‘I have seen the Pig at Spring-gardens, and he sadly disappointed me!’) but Toby was more than a performer – he was the author of an autobiography. Though he may have had some help from his trainer, Nicholas Hoare, the short account is, apparently, all Toby’s own work and reads like a standard showbiz tale of rags to riches – absent father, many siblings, adoption, early promise recognised, vigorous training, and the London debut:

‘when I was formally announced to perform, I became the topic of the day … and the most arduous task I should ever have to accomplish, was now before me. Those who have been in a similar situation, can alone be able to conceive what I must have felt: as the time grew nearer, it was dreadful; however, I possess a strong nerve, and some small share of confidence, which, I was convinced, would greatly assist me….’

The Stage’s Hamlet would have been proud.

To discover more about the V&A Theatre and Performance Collections visit Search the Collections and Search the Archives.

After so many try finally I visit this and know every and keep points which would be helpful for me. I want to say thanks a lot.