While luxury is often marketed and understood in the media through objects – produced by designers and brands notable for their heritage, prestige and sophistication – selecting objects that enabled us to interrogate the concept of luxury in an exhibition format became one of our greatest challenges. On the one hand, there are so many extraordinary examples of objects from within the museum’s own collections which have a deep resonance with contemporary understandings of luxury – far too many to be contained within one exhibition. Another challenge is that objects are not inherently luxurious, and are only ascribed with luxury in relation to their use, interpretation and perceived value within a social context. Furthermore, in any given context, the meaning and value of an object can be multivalent and ultimately ambiguous. What is it about an object that makes it luxurious? In ascribing luxury to an object, what definitions and values are being prioritised, and by whom?

Monkey Business by Studio Job is the type of object that raises exactly these sorts of questions. Described as a ‘shimmering sculpture’ by the designers, it is a large gilded bronze trunk, LED-lit from within, adorned with a monkey. The monkey is encrusted in Swarovski crystals and wearing a small red hat with a golden tassel, in the style of a fez. He is straddling the top of the trunk, his fingers clasped around its lid, with an expression of surprise painted across his face. One wonders what the monkey is up to: is he shielding or is he stealing the treasures concealed within? The position of his fingers prevents the trunk from closing, subverting its essential function of protecting its contents. The name Monkey Business, with its references to illicit and illegal behaviour, further arouses suspicion about the monkey engaging in a surreptitious act.

The monkey is a longstanding motif within European art and design since at least the 17th century. ‘Singerie’ emerged as a genre of satirical painting, in which monkeys were depicted ‘aping’ human behaviour. The Flemish painter David Teniers the Younger was particularly active in the genre, completing hundreds of paintings of monkeys at ale-houses, smoking parties, concerts and barbershops. The monkeys are often dressed in fashionable attire, as the paintings aimed to parody the most elegant and powerful in society. Singerie was marked by a distinctly anti-establishment tone, with the monkey representing the persistence of mankind’s more duplicitousness and base instincts – particularly at the higher end of the social order. Singerie motifs became popular across the decorative arts, featuring extensively as part of the 18th century French Rococo interior.

The organ grinder’s monkey emerged in the early 1900s and again captured the popular imagination. Organ grinders were novelty street performers who travelled throughout the working class neighbourhoods of New York and Europe, ‘grinding out’ popular tunes from the day for spare change. They were often accompanied by a small monkey who was used to draw in crowds and collect money from a tin cup. The organ grinders were almost universally regarded with wariness and disdain, the horribly atonal noise they generated viewed as an annoyance and their work as a thinly veiled pretext for extorting money from passersby. The monkeys often appeared as an extension of their shadiness and cunning. Typically dressed in a coloured vest and small hat resembling a fez, the monkey also embodied many occidental fears and suspicions regarding the ‘oriental’ other.

While organ grinding has long ceased to be a common profession, the organ grinder monkey continues as a recurrent figure in popular culture. It was immortalised as Charley Chimp, a mechanical cymbal-banging toy manufactured from the 1950s to 1970s, and was also the inspiration for the character of Apu in Disney’s Aladdin – a comically volatile monkey thief who becomes the protagonist’s sidekick. While he is depicted as a loyal companion to Aladdin, he nevertheless remains an adept pickpocket with an unconquerable penchant for precious jewels.

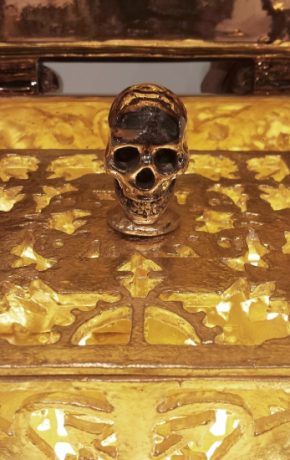

By virtue of its visual references, Studio Job’s showy monkey can also be understood as an extension of these historic depictions, embodying the physical characteristics and guile of the organ grinder monkey and perhaps also mirroring our own base desires. Additionally, the object as a whole can be read as a postmodern expression of the history of empire. The fez, for example, originates from Morocco but became a symbol of the Ottoman Empire in 1832 under Mahmud II, to be worn by Muslims and non-Muslims alike as a gesture of unity. In 1925, a Hat Law was passed by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk to outlaw the wearing of the fez in modern Turkey, decrying it as a symbol of Ottoman decadence. On the other hand, the monkey whose ‘Turkishness’ it might be deemed to imply is in fact modelled after the capuchin monkey, which originates from Central and South America. They were given their name by the Spanish conquistadors after the Order of Capuchin Friars on account of their dark ‘cloaked’ bodies and pale faces. The trunk’s blue and white ceramic handles reference traditional Delftware, introduced in the Netherlands as a substitute for more expensive imported Chinese porcelain in the 17th century. The raised pattern which adorns the trunk’s gilded surface derives from Studio Job’s own lexicon and is an assembly of recognisable icons including cow skulls, dollar signs and wine goblets.

With its assemblage of symbols and signalling, Monkey Business remains open to multiple interpretations. It playfully resists easy classification, relating to style and function, instead raising a number of questions about its intended audience and meaning. What does the use of extravagant materials communicate about the object’s value? Is its opulence to be taken at face value, or as a subversive commentary on ideas of conspicuousness and taste? What are the motivations of the designer to create such an object? Who is this object for?

These are among the questions that we will be asking during an evening event at the museum. On Friday 17 July, we will be joined by Job Smeets of Studio Job and Jan Boelen, Director of Z33 and Head of the Social Design Programme at Design Academy Eindhoven, to discuss his design practice and its relationship to definitions of 21st century luxury.

Defining Luxury: Job Smeets and Jan Boelen in Conversation

The Lydia & Manfred Gorvy Lecture Theatre

how much tho