A flurry of last-minute withdrawals meant that Object Pitch Day 6 was less packed than previous sessions. Who can blame the dropouts? As previous days had shown, the competition was certainly fierce and only the best object-based research was going to make the final cut.

As today’s knock-out series of pitches showed, that bar was only going to be set ever higher…

OP6/01

We began with Avalon Fotheringham, Research Assistant on the forthcoming Fabric of India exhibition, who took us well beyond the walls of the V&A, covering “more worlds per second than any previous pitcher” (according to Bill Sherman, Head of Research at the V&A) and clocking in at a cool three minutes.

Avalon explained how her choice of object for A history of an OBJECT in 100 worlds was the result of discussions with Rosemary Crill, curator of Fabric of India, and their shared belief that the project “needed something Asian”.

Reflecting its place in global design history, Avalon’s selection was “an object with a marvellous history – one that’s very deeply connected with the V&A’s own history, as well as being representative of an expansive, wider story of design connecting people from all around the world”.

Without making the big reveal, she deadpanned, “After an intro like that, you might be expecting something rather more fabulous than something a few of you might have a version of in your pockets right now”. We were certainly intrigued…

Her story began with a prominent figure in the early history of the V&A, Caspar Purdon Clarke, later Director of the museum. In 1882, Clarke was sent to India with “£5000, £3000 of which was provided by the Prince of Wales himself to purchase goods for the new Indian section at the South Kensington Museum”. On his buying trip, he “purchased more than 1000 pieces of textiles and dress as examples of quality design for the education of British manufacturers”.

This haul included “a length of handkerchiefs, from an area of India called Berhampur, in West Bengal”. Made in silk, it was dyed in a pattern of white and red spots on purple, and was “designed to be cut and hemmed into eight individual square handkerchiefs”. Avalon explained how the pattern was “achieved through a tie-dye technique referred to as ‘bandhani’, the origin of the word bandana”, and an object type that turned into “the spotted handkerchief as we now know it”.

Avalon then showed how her object “takes us around the world, and from at least the 18th to the 21st century”: from India, “where it was a highly useful object for everything from accessorising, to performing as the preferred weapon of gangs of stranglers”, to England, “where its direct import was prohibited by protectionist laws for a century”. In spite of this, and reflecting its massive popularity, “hundreds of thousands were smuggled in annually – often through outright theft”.

Avalon’s international pitch didn’t stop there, but jumped to West Africa, where her object was re-exported and “among the goods traded for slaves”; America; the West Indies and South East Asia.

She then elaborated the even wider contexts suggested by Indian spotted handkerchiefs, with a history that is “wrapped up in that of industrial development”, and which “transcends class boundaries, crosses cultures and continents, and extends over eras”.

After an expansive pitch that crossed time and space, Avalon revealed a compelling detail about her particular object: that it “is the only known complete length of Bengali silk tie-dyed handkerchiefs in existence”, making it “the last survivor of a tremendous trade” – one that “spawned any number of variations, imitations and successors”.

She finished by reiterating the key theme of her illuminating presentation: how “an unassuming length of spotted handkerchiefs truly represents a type of object whose use and significance stretches across continents and cultures, and opens the door to 100 worlds – if not even more…”

OP6/02

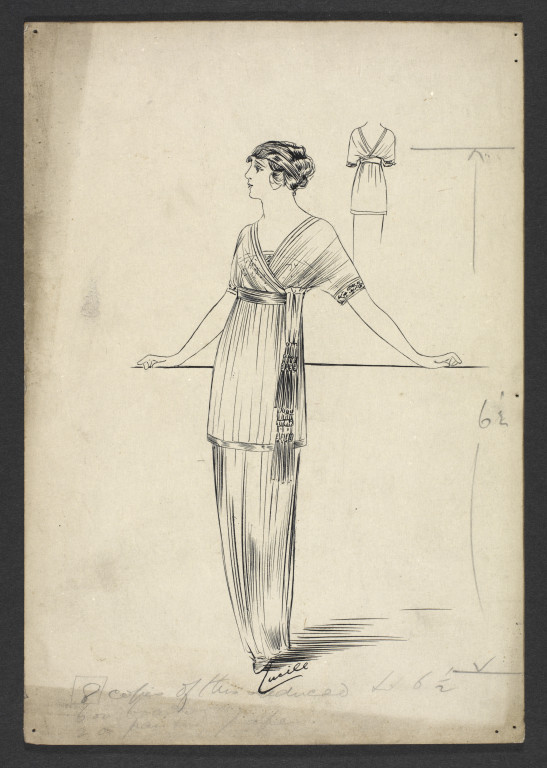

Next up was Cassie Davies-Strodder, curator of 20th and 21st century fashion, who made her case for a purple silk dress by Lucille made in London in 1912.

Surprisingly Cassie was the very first person to pitch an item of clothing, with only her colleague in Fashion and Textiles, Sonnet Stanfill, choosing a fashion accessory in the form of the Oliver Goldsmith ‘Jester’ sunglasses featured in Object Pitch Day 2.

This is in spite of the V&A being “renowned for its dress collections, the Fashion Galleries being the most popular galleries in the museum, and fashion exhibitions acting as a huge draw for visitors”. Explaining her choice, Cassie argued, “We all have a connection to clothing as we all have to clothe our bodies”.

Moving onto the specific details of her object, Cassie told us that the dress “touches on many, many worlds”, including those of designers, clients, makers, sweated industries, society London, the Orient, unmarried women, shopping, literary circles, LGBTQ histories, museology and even “people who like ‘Downton Abbey’”.

Cassie set the scene for her dress, as something “made and worn at the end of the Edwardian period, in the decade leading up to the First World War”, a period described by the French chef and restaurateur Marcel Boulestin as “a prelude to a new era, like a splendid crescendo of luxury, pleasure, happiness, artistic glory, opening with the glow of the Coronation and finishing fortissimo in August 1914 when the first guns sounded the knell of civilisation”.

She told us that the design of the dress “marked a transitional point in fashion, from the fussy froufrou dresses of the Edwardian period and the simpler styles that came in after the war, and that led to the birth of the modern woman’s wardrobe”. Its upright silhouette, “known as the Directoire line”, has been credited to French designer Paul Poiret, as have the “Eastern or oriental influence” evident in its design – features that also attest to the impact of the Ballet Russes, “who were taking London and Paris by storm in 1912”.

Attending to the social life of the dress, Cassie explained that it was “worn at a time when upper-class women changed their clothes up to six times a day”, providing insight into a “whole world of extinct etiquette rules”. Using the example of the colour purple, she revealed that it was both fashionable and indicative of half mourning, a phrase that is itself redolent with the careful calibration of dress during this period.

Cassie then moved onto the designer of ‘her’ dress, Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon, the name behind Lucille, who was “one of the best known designers of the early 20th century”. Duff-Gordon claimed in her memoires to be “the first to use fashion shows, the first to make models into notable personalities and the first to create destination shopping with her salon that was furnished with luxury fixtures, as well as places to play cards and have tea”.

A “uniquely early 20th-century figure”, Duff-Gordon was considered very daring as an aristocratic divorcee who went into business to support her daughter. An international success story with branches in London, Paris and New York, she also famously survived the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

The dress, a “bespoke couture garment”, was also an example of what Lucille described as a “personality dress made to the client’s specific needs”. The design process reflected this, as can be seen in sketches she sent to clients, such as the one showing the V&A’s dress in the Archive of Art & Design.

Demonstrating this highly personal, luxury service, Cassie showed where “more elaborate sequin and metal-thread embroidery motifs” had been added at the behest of the wearer.

Showing how some things don’t change, she then disclosed how “behind the celebrity designer were many, many anonymous makers, who all took part in creating the finished garment”. These wider creative inputs included those of the textiles trade – including silk weavers and silk dyers in Italy, and the salesmen who supplied the textiles – as well as personnel inside the fashion house, such as the vendeuse who “arranged the three or four fittings necessary for a dress like this”, the cutters, fitters, seamstresses and embroiders.

With such a luxury commodity, there was a “vast gulf between the makers and wearers”: a dress like the one Cassie showed us “cost the same as a seamstress’s yearly wage”.

Significantly, we can link this particular dress to a specific named wearer: Heather Firbank, who wore it when she was 24.

Cassie then explained how her object provides a useful way into wider discussions of wealth and class in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and, more surprisingly, perhaps, to literary and artistic circles. One of Heather’s three brothers, and the one she was closest to, was Ronald Firbank, the well-known playwright and author, whose works predominantly feature “dialogue and snatched conversations between glamorous, vacuous characters”. His writings are also replete with allusions to contemporary fashion designers, including Lucille, with his regular correspondence with Heather showing how “she kept him up to date with changing fashions and sent him copies of Vogue”.

This world of luxury and glamour contrasts with the surprisingly dark side to the dress’s history that Cassie also revealed. “Like many women of the time, her fate was largely in the hands of men”. While she grew up with great wealth, her father’s poor investments lost most of the family’s fortune, and her father and two of her brothers – Hubert and Joseph – were dead by the time she was 25.

Heather remained unmarried and, as a single woman, was “entirely reliant on male relatives for travel, housing and income” – a situation that was exacerbated by the death of Ronald, her last surviving relative, in 1924, the same year she put into storage “her vast and expensive wardrobe of clothes”.

Moving onto her final world – the V&A – Cassie told us that 200 items of Heather’s clothing, including the dress she pitched, had been acquired by the museum after her death. She explained how the collection is “incredibly important to the Fashion and Textiles Department and the story of displaying fashion in the museum”, with the year of its acquisition, 1957, the same year that the V&A appointed its first curator of dress, Madeleine Ginsburg.

Before this date, fashion and dress were not as highly regarded within the V&A’s collections as they are now, with Cassie quoting Ginsburg’s comment that, “We never had any freedom. Dress was a new priority. It had nothing in common with antiquities and intellect – it was a battle”.

Heather Firbank’s wardrobe was shown in the V&A’s very first exhibition of 20th-century fashion, ‘Lady of Fashion: Heather Firbank and What She Wore Between 1905 and 1925’: a display that “put fashion on the map at the V&A and even had to be extended as, like today, beautiful dresses attracted people in droves”.

The Firbank Collection has since “featured in a Circulation Department touring exhibition, in every version of the Fashion Galleries in gallery 40 and in numerous other exhibitions and publications”, placing it in a unique position from which to “track history and trends in displaying dress”. In fact, as Cassie revealed, the Firbank collection is a “victim of its own success”, with ‘her’ dress “faded irrevocably under museum lights” – deterioration that suggests the vital work done as part of conservation and collections care.

In summing up, Cassie touched on another major sea change in how we engage with objects. As she argued, we “wouldn’t even be here describing this dress or Heather without changes in museology and object research”. Where once it was appropriate to focus exclusively on who designed an object, the V&A is now just as interested in who owned and used it. To borrow Cassie’s extremely judicious phrase: “We look at stories as well as histories”.

OP6/03

Object Pitch Day 6 ended with Louise Shannon, Curator of Digital Design. Appropriately enough, she made her case for Minecraft, becoming the very first person to propose a digital object. Like Avalon, Louise’s choice was informed by discussion with her colleagues in Contemporary Architecture, Design and Digital.

Louise’s pitch explored how Minecraft, in spite of being a “very young object”, has already “had an extraordinary impact in terms of video games, wider design culture and, indeed, beyond”.

She reiterated this newness by outlining its very short history: created by a Swedish programmer, Markus ‘Notch’ Persson, it was later developed and published by the small independent company Mojang, with an initial release for the PC on 17 May 2009 followed by a full release version on 18 November 2011. As of 25 June 2014, 54 million copies had been sold across all platforms, with Microsoft announcing a $2.5-billion deal to purchase the game and all its Intellectual Property in September 2014 – ‘for a company that’s only 3 years old that’s extraordinary’

For those of us born on the wrong side of the Digital Age, Louise helpfully explained that Minecraft is an “open-world video game” that allows players large amounts of freedom in how they play with it. She illustrated this by telling us that although the game’s default narrative mode is first person, there is also the option of playing in the third person.

At the start of a new game, the player is placed on “the surface of this huge procedurally generated infinite world, which is just waiting for you and your creativity”. The “core game play” involves breaking and placing 1m-square blocks, which are arranged on a fixed grid to create the game world. These cubes “represent a range of materials including dirt, grass, stone, metal ores (for mining), water, trees, animals” and, as Louise explained, most players use these virtual resources “to create small villages, houses and settlements”.

“Passionate, dedicated communities” of makers and designers have taken Minecraft much, much further, creating extraordinary builds, such as the “floating castle, hundreds of metres up and composed block by block” that Louise showed us. As she went on to demonstrate, nothing seems to be beyond the expertise of these enthusiasts, who have “recreated film sets, entire episodes of the television series Game of Thrones, and produced a scene-by-scene recreation of Star Wars”, using modifications that “help break the rules of the game to enable their boundless creativity”.

Moving beyond the world of video games, Louise then shared other exciting and sometimes surprising applications of Minecraft. As she explained, the “whole of Denmark was recently reproduced in Minecraft by the Danish government”. These maps, created to be used as an educational tool, are intended to support “virtual fieldtrips to hard-to-reach parts of the country”, but also “let people look at their local environment in different ways”.

Louise then showed us that Minecraft isn’t merely a matter of representing real and imagined places: it can also be used to redevelop public spaces in the non-digital world. To demonstrate this, she cited the Block by Block project, a four-year partnership between the United Nations and the makers of Minecraft, Mojam, which aims to upgrade 300 public spaces by 2016. Block by Block “involves young people in the planning of urban spaces using Minecraft as a tool to help them think about their local environment”.

One iteration of the project has seen the waterfront in Haiti – currently “totally unprotected from sea and regularly suffering from flooding and erosion that badly affect settlements in the area” – recreated in Minecraft so that “an array of solutions can be imagined using the knowledge of local community”.

Referring to another Block by Block initiative, this time in Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Louise revealed how Minecraft has already had real impact in redesigning public spaces in the town. Showing this image, she told us that the improvements were “first fashioned in Minecraft before being realised in the ‘real world’”, most noticeably the barriers that stopped people falling into the water.

In concluding, Louise reiterated her core argument: that “Minecraft is not just a story about video games: it’s also about the communities that play them, their creativity and, more importantly, how it impacts on how we live our lives in public today”.

***

Object Pitch Day 6 proved the old adage that quantity is by no means the same as quality. In just three pitches, we were brought right around the globe and into worlds as diverse as those of international trade in the 18th and 19th centuries, fashion houses before the First World War and the newest developments in computer game design.

Notably, although Avalon, Cassie and Louise’s pitches dealt with very different issues, ideas and object types, they are also hugely suggestive of how the V&A acts as a site where knowledge and expertise are shared, and where we thrive on discussions with our colleagues. Significantly, each of their talks also meditated on significant moments in the V&A’s own history: from Caspar Purdon Clarke’s buying trip to India, through changing attitudes to the acquisition and display of fashion and dress in the mid-20th century, to how the museum actively engages with the very latest advances in digital design.

With only two Object Pitch Days left, our impossible decision was edging ever closer…