‘Punch is such a droll, diverting vagabond, that even those who have witnessed his crimes are irresistibly seduced into laughter by his grotesque antics and his cynical bursts of merriment, which render him such a strange combination of the demon and the buffoon.’

- Thomas Frost, The Old Showmen, 1881

Itinerant Commedia dell'Arte performers, anonymous pencil and wash drawing, undated. Museum no. S.726-1997. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Punch Arrives in England

Punch in the 17th century

A puppet play that would have featured a version of Punch was first recorded in England in May 1662, by the diarist Samuel Pepys. He noted seeing it in Covent Garden, performed by the Italian puppet showman Pietro Gimonde from Bologna, otherwise known as Signor Bologna:‘Thence to see an Italian puppet play that is within the rayles there, which is very pretty, the best that ever I saw, and a great resort of gallants.’

- Samuel Pepys Diary, 9 May 1662

Bologna was one of many entertainers who came to England from the continent following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Unlike today’s Punch and Judy, performed with glove puppets in canvas booths with the audience outside, Bologna used marionettes – puppets with rods to their heads and strings or wires to their limbs – and performed within a transportable wooden shed, and as such would have been quite a novelty.

Pepys was so delighted by the show that he brought his wife to see it two weeks later, and in October 1662 Bologna was honoured with a royal command performance by Charles II at Whitehall, where a stage measuring 20ft by 18ft was set up for him in the Queen’s Guard Chamber. The king rewarded ‘Signor Bologna, alias Pollicinella’ with a gold chain and medal, a gift worth £25 then, or about £3,000 today.

Other Italian puppeteers appeared in London, and on 10 November 1662 Pepys took his wife to see another show in a booth at Charing Cross performing: ’the Italian motion, much after the nature of what I showed her at Covent Garden.’ This may have been the show of Anthony Devoto who had a puppet show at Bartholemew Fair, and at Charing Cross in 1667, 1668, 1669 and 1672, when a warrant of 11 November 1672 permitting him to ‘Exercise & Play all Drolls and Interludes’ referred to him as: ‘Antonio Di Voto puncinello.’ Devoto’s booth was visited by the other famous 17th century diarist John Evelyn who referred to it as: ‘the famous Italian puppet play’, but by 1675 the site was cleared and Devoto’s booth was replaced with a statue of Charles I.

Pulliciniello, the Commedia dell’Arte servant, Engraving by Jacques Callot, about 1622. Museum no. S.5290-2009. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The exact nature of the shows that Pepys saw remains unclear, but we know one of them was accompanied by dulcimer music, and that Punch, as his name was anglicised, would have been one of several characters, his role providing comic relief in whatever the subject of the play.

Pepys usually referred to the shows as Polichinello, a name relating to Punch’s roots in the Italian ‘commedia dell’arte’, where masked actors improvised comic knockabout plays around a number of stock characters, and Polichinello was the subversive, thuggish character whose Italian name Pulcinella or Pulliciniello may have developed from the word pulcino, or chicken, referring to the character’s beak-like mask and squeaky voice.

Commedia dell’arte developed in Italy in the mid 16th century, and an anonymous 18th-century drawing depicts an itinerant family of masked performers, in costume as they travel, the father dressed as Pulcinello in his characteristic white costume and tall hat.

Troupes of Commedia actors established themselves in France, where a print by Jean Bérain (1638 - 1711) published in Paris in the early 18th century depicted a masked Punch character appearing on the French stage. He is not a puppet, but his nose, chin and pot belly indicate his ancestry to the Punch we know today, while his stance indicates a comic, bird-like walk.

Like his Italian ancestor, Punch always carried a big stick or 'batone', as the Italians called it, with which to fight his opponents, despite it sometimes being used to beat him. Today a wooden stick split at one end is often used, to create the percussive noise of the magic 'slapstick' traditionally used by Harlequin in early pantomime.

The tradition of marionette shows featuring Polichinelle was established in Paris by the mid 17th century, when a puppet show performed by Pierre Datelin (1567 - 1671), known as Jean Brioché, included the character in the marionette shows he established at the great fairs of Saint-Laurent and Saint-Germain. The puppeteers that Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn saw in the 1660s and 1670s may well have been presenting Italian shows as performed in France, and we know that Signor Bologna performed at the Saint-Laurent Fair in Paris in 1678, with marionettes including his: ‘Roman Policinel’.

Punch and his ancestors always had a ridiculous voice, even on the human stage. At London’s May Fair in 1699 the commentator Ned Ward described a puppet show: ‘where a senseless dialogue between Punchinello and the Devil was conveyed to the ears of the listening rabble through a tin squeaker.’ Punch’s characteristic voice comes from the use of a reed retained at the back of the Punchman’s or ‘professor’s’ mouth, calling for expert alternation of reed use when Punch is talking to other characters. In Britain the reed is called a swazzle, and in France a sifflet-pratique. Its most common Italian name was pivetta, but also sometimes strega, or witch, and franceschina, after Franchescina, one of Punch’s wives in the commedia dell’arte who had a voice like a witch. Swazzles are made of thin metal today, but bone or ivory were formerly used, each equally tricky to master and easy to swallow.

Covent Garden Piazza

Covent Garden Piazza, hand-coloured engraving. Museum no. S.3726-2009. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Deschars en habit de Polichinel au Divertissement de Villeneuue Saint-Georges

Deschars en habit de Polichinel au Divertissement de Villeneuue Saint-Georges, engraving by Jean Bérain, published in Paris by J. Mariette. Museum no. S.3837-2009. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The Italian Puppet Show, engraving after the original by Samuel Collings, published 1875. Museum no. S.943 - 2010. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Punch Settles In

Punch in the 18th century

Mr Punch made himself thoroughly at home in Britain during the 18th century. His wife was the shrewish Dame Joan who made his life a misery, and his hunched back and pot belly became more pronounced.

The marionette Punch was the celebrity disrupting the action in puppet plays all around the country, in established puppet theatres and in fairground booths where puppets were a popular feature of all the great fairs and small country wakes throughout the century. Punch provided comic relief, and in 1728 the satirist Jonathan Swift mentioned the excitement generated at fairgrounds by his curious voice:

'Observe the Audience is in Pain

When Punch is hid behind the Scene,

But when they hear his rusty Voice

With what Impatience they rejoice.'

- Jonathan Swift: A Dialogue Between Mad Mullinex and Timothy, 1728

Habit de Polichinel Napolitan, Hand-coloured engraving by Francois Joullain, illustration from Riccoboni’s Histoire du Theatre Italien by Luigi Riccoboni, published by Cailleau, Paris, 1731. Museum no. S.1215-2010. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Punch was a leading character in the marionette shows of Martin Powell (d.1725), the puppeteer who tapped into the taste of the town for puppets, making himself wealthy and Punch more famous. Powell had a marionette theatre in Bath in 1709 where Punch and Joan danced in Noah’s Ark in the biblical play The Old Creation of the World, and by 1710 Powell was performing in London, in St. Martin’s Lane, in a room adapted as a puppet theatre, and in 1711 he moved to the Seven Stars, a tavern in Covent Garden’s Little Piazza where his plays were performed with quite elaborate scenery, and candle footlights.

Punch did not yet have his own play but featured in a variety of Powell’s plays, some lampooning famous people, or satirising theatrical fashions such as Italian opera. In The False Triumph we hear that: ‘Signor Pulcinella appeared in the role of Jupiter, descending from the clouds in a chariot drawn be eagles and sang an aria to Paris.’ Whatever the story, it was customary for Punch to fight the Devil, traditionally the adversary of Vice in mediaeval Morality plays. Sometimes the Devil won, as mentioned in passing in the epilogue of a play of 1741:

'Our catastrophe

Does not with puppet rules agree;

Vengeance for Punch’s crimes should catch him.

And at last the Devil fetch him.'

More usually Punch was victorious, and in 1765 Dr. Johnson recalled the Devil being: ‘very lustily belaboured by Punch’.

Punch had a marionette theatre named after him in 1738 when the actress and puppeteer Charlotte Charke (1713 - 1760), daughter of the actor and playwright Colley Cibber, was granted a license to open Punch’s Theatre in James Street, off the Haymarket. Her wooden cast was provided with elegant scenery and costumes for satirical marionette plays, or versions of those on the regular stage, with Punch the novelty character performing roles such as Falstaff, or dancing with his wife Joan. As she wrote:

'For some time I resided at the Tennis-Court with my Puppet Show, which was allowed to be the most elegant that was ever exhibited. I was so very curious that I bought mezzotintos of several eminent Persons, and had the faces carved for them. Then, in regard to cloaths, I spared for no cost to make them splendidly magnificent, and the scenes were agreeable to the rest.'

- Charlotte Charke: A Narrative of the Life of Mrs Charlotte Charke, 1755

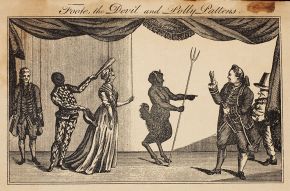

Foote, the Devil and Polly Pattens, The Macaroni & Theatrical Magazine, February 1773. Museum no. S.1004-2010. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The enterprise was short-lived. She sold the marionettes while on tour, but where Powell and Charke led, others followed suit. Punch was such a popular character that when the actor Samuel Foote (1721 - 1777) produced his ‘Primitive Puppet Show’ the satirical play The Handsome Housemaid; or, Piety in Pattens at the Haymarket Theatre on 15 February 1773, featuring real actors and life-sized figures with strings attached, the audience in the upper gallery created a disturbance and tore up the benches on the opening night, partly because of the absence of Punch. As The Morning Chronicle noted:

'…from the illiberal, unmanly conduct of the gallery, it seemed as if some of the persons had come to the theatre, not in hopes of seeing a primitive but a modern puppet-shew, and that they grew out of temper because Punch, his wife Joan, and Little Ben the Sailor, did not make an appearance.'

- The Morning Chronicle 16 February 1773

Foote revised his show, introduced songs and a human Punch, seen by the curtain stage left in an illustration of a scene from the play published in a contemporary magazine.

As Charlotte Charke had found, marionette shows were expensive to operate, and by the end of the 18th century glove puppet versions of the Punch show, performed in small portable booths became a familiar sight on city streets and country lanes instead. An illustration of such a show published in London in 1785 refers to it as ‘the Italian puppet show’, supporting the theory that the glove puppet Punch shows were performed by a new influx of Italian showmen in London. Punch was here to stay, with no strings attached, and while Punch integrated himself in Britain a similar process took place in other parts of Europe, resulting in Punch’s European cousins including Kasperle in Southern Germany and Austria, Polichinelle in France, Karakoz in Turkey and Petrushka in Russia.

Punch in the Drawing Room, illustration from The Graphic, 25 December 1871. Museum no. S.689-2010 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Punch the Glove Puppet

Punch in the 19th century

Punch and Judy shows were familiar sights on the streets throughout the 19th century, their performances often heralded by a drums or panpipes played by the Punchman’s accomplice or ‘bottler’ whose job collecting the money in a bottle gave rise to his soubriquet. In 1801 Joseph Strutt described the meagre existence of a contemporary puppeteer:

'In the present day the puppet-show man travels about the streets when the weather will permit, and carries his motions with the theatre itself, upon his back. The exhibition takes place in the open air; and the precarious income of the miserable itinerant depends entirely on contributions of the spectators, which as far as one may judge from the square appearance he makes, is very trifling.'

- Joseph Strutt: Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, 1801

Vingette by Ann Dibdin, aquatint by John Hill from Charles Dibden’s Observations of a Town 1801-1802. Museum no. S.937-2010. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

An 1801 engraving of a country Punch and Judy show in a booth depicts Punch still wearing the sugar-loaf hat or coppolone, and the white smock of his Italian relations, similar to that worn in the Italian show in Rome depicted by Pinelli in 1815. But generally Punch in England had discarded his plain white Italian costume by the middle of the 18th century and had started to wear the red and yellow motley of the English jester or fool.

With Punch’s move from marionette stage to portable booth came new clothes and new companions. By 1825 we hear in Bernard Blackmantle’s The English Spy of his wife being called Judy instead of Joan: ‘old Punch with his Judy in amorous play’, and of Punch’s having a Toby the dog, usually played by a real dog.

A dancing Punch was a star of the stage at Covent Garden Theatre in November 1825, when the comic French acrobatic dancer Charles-Francois Mazurier (1798 - 1828) made a hit with his comic Punch dance in The Shipwreck of Policinello, a play by Jean-Baptiste Blache. Mazurier had made a success with the role in Paris in 1823 at the Porte Saint Martin Theatre, under its original title Pulcinelle Vampire. The manager Charles Kemble’s address to the audience at Covent Garden noted Mazurier’s hump, and his similarity to a marionette:

'Come, all ye admirers of Punch,

Come and gaze on our Policinelle,

Did ever a soul wear a hunch

Or scream with his voice half so well?And his joints are so supple they seem

As if they were hung upon wires;

And his leaps, and his walks, and his screams,

Are what every Parisian admires'

- Charles Kemble’s Address. Reprinted in The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction, 19 November 1825.

The earliest script of a Punch and Judy show dates from 1827 when the journalist John Payne Collier visited Piccini, the 82-year old Italian Punchman who had worked in London since he arrived in 1779. Collier was to record the script at a special performance, while the artist George Cruikshank drew each scene. Cruikshank noted that the script was: ‘a faithful copy and description of the various scenes represented by this Italian, whose performance of Punch was far superior in every respect to anything of the sort to be seen in the present day.’ Punch historians have doubted the veracity of the script, but the illustrations vividly recreate the action and characters, many of which we know today. Some, like Pretty Polly, the Scaramouch with his extending neck, and the Blind Man, are more unfamiliar but relate to characters that existed in Italian versions of the story.

Punch and Judy show, possibly by George Cruikshank, 19th century. Museum no. S.675-2010. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Punch and Judy shows were not just for children in the early 19th century. Aspects of the comedy such as the marital strife between Punch and Judy, and in Piccini’s show the relationship between Punch and his girlfriend Pretty Polly, obviously struck a chord with many adult members of the audience. Punch was a well known celebrity with the satirical magazine named after him in London in 1841, children’s picture books published based on his shows, and images of him proliferating on all manner of household artefacts, from doorstops to baby’s rattles.

As today, some censured the shows for Punch’s violent behaviour, but Punch and Judy found an ally in Charles Dickens, whose novels include several references to the shows. Dickens defended them as enjoyable fantasy that would not incite violence:

'In my opinion the Street Punch is one of those extravagant reliefs from the realities of life which would lose its hold upon the people if it were made moral and instructive. I regard it as quite harmless in its influence and as an outrageous joke which no one in existence would think of regarding as an incentive to any kind of action or as a model for any kind of conduct.'

- Charles Dickens (1812 - 1870) Letter to Mary Tyler, 6 November 1849

Many clearly agreed with Dickens, and Punch continued to gain respectability when Punchmen were invited to perform in private homes, where they probably modified and adapted their show to suit a more refined audience. The Punch and Judy showman interviewed by Henry Mayhew in 1851 mentioned the evening (or ‘hevening’) parties at which he performed:

'We do most at hevening parties in the holiday time, and if there’s a pin to choose between them I should say Christmas holidays was the best. For attending hevening parties now we generally get one pound and our refreshments – as much s they like to give us.’

- Henry Mayhew (1812-1887): London Labour and the London Poor

A Punch and Judy show was performed by John Philip Carcass (1865 - 1938) for Queen Victoria at Osborne House, and Punch and Judy shows were certainly considered suitable entertainment for Victorian Christmas celebrations, as can be seen from an illustration in The Graphic in December 1871 showing an audience of immaculately dressed children watching Punch brandishing his stick from the booth, with the drummer or ‘outside man’ in the foreground.

Punch and Judy even crossed the Atlantic in the late 19th century. A 'merry dialogue between Joan and his wife' featured in what was probably a marionette show in Philadelphia in 1742, and in 1850 a Punch and Judy show was performing at Sandy Bar in San Francisco. When William Judd (b.1841) emigrated to the States in 1867 he developed a business selling ‘everything needed for a travelling Punch and Judy show including a: ‘Superior Punch and Judy Theatres’ and carved wooden figures, most costing $1.75, but the crocodile $2, Hector the Horse $1.50, a baby 50 cents and a cudgel 10 cents. Richard Codman II (1865 - 1951) performed in the States twice, and in 1892 performed in, his dog Toby received lavish praise from The Boston Globe’s columnist reviewing the show at Austin & Stone’s museum in Boston.

Il Casotto dei Burattini in Roma

Il Casotto dei Burattini in Roma. Engraving by Pinelli, 1815. Museum no. s.1213-2010. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Monsieur Mazurier in the Character of Polchinelle

Monsieur Mazurier in the Character of Polchinelle, print, 19th century. Museum no. s.3224-2009. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Punch and Judy

The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Punch and Judy, illustrations by George Cruikshank, about 1859. Museum no. S.929-2010. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Preparing for the Fair

Preparing for the Fair, print, Illustrated London News, 1883. Museum no. S.684-2010. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

A Punch and Judy show at Ilfracombe, photograph by Martin Paul, 1894. Museum no. 1886 - 1980. © Victoria and Albert Museum

Punch at the Seaside

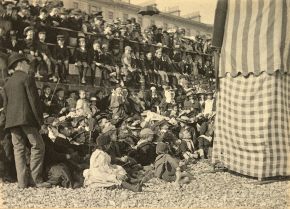

Another place that Punch found audiences as the century progressed was at the seaside, on the beach or the newly fashionable seaside piers. Victorian seaside resorts became the fastest growing towns in Britain in the latter part of the century. The introduction of railways and later of excursion trains catering for crowds meant that more people could visit the seaside and take advantage of the increased leisure time resulting from reduced working hours, and the August Bank Holiday introduced in 1871. Splendid new hotels catered for prosperous visitors to stay, while day-trippers joined the throng and had time to enjoy the Punch and Judy shows that began to be a standard part of the entertainment on offer.By the end of the century a Punch and Judy show could attract huge audiences, as shown by Martin Paul in his photograph of a Punch and Judy show at Ilfracombe in 1894.

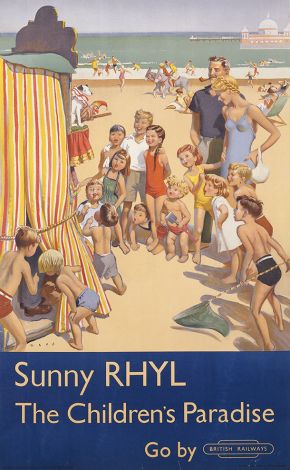

Sunny Rhyl by Douglas Lionel Mays, issued by London Midland Railways, 1952. Museum no. E.274-1952. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Punch in the 20th century

Puppetry in Britain declined generally in the early 20th century with audiences drawn to other forms of entertainment including music hall, variety and cinema, and from the 1950s, television that introduced new puppet characters to children in the popular programmes. Some Punch and Judy showmen continued to work street pitches in towns and cities in the early 20th century, but traffic conditions made it increasingly difficult. At the seaside however Punch and Judy continued to be a popular feature of entertainment, especially for children, except in wartime when many Punchmen were serving in the forces, and British coastal towns were prohibited areas. The Punchman Percy Press gave hundreds of shows with ENSA during the Second World War to the troops however, with Punch in battledress and a gas mask, Judy into a NAAFI cap, and a Hitler doll instead of the hangman Jack Ketch who is always hanged by Punch.

In 1951 there was a Punch and Judy show in Battersea Park for the Festival of Britain, but by 1952 when the poster Sunny Rhyl was published, Punch and Judy shows were most commonly found at the seaside, and almost exclusively regarded as children’s entertainment. This poster shows an audience of children except for the parents as token adults, not a welcome situation for the ‘bottler’ collecting money at the end of the show.

Many of the Punch and Judy showmen or ‘professors’ performing during the first half of the 20th century were carrying on an oral tradition, performing shows that their fathers or grandfathers had developed, often with figures they had made. Known as the ‘swatchel omis’ they included the Staddons of Weston super Mare, the Maggs of Redruth and Bournemouth, the Smiths of Poplar including Albert Smith who worked in London in the 1930s and his brother Charlie who gave up his Margate pitch in 1963, and the Codmans – Richard Codman I who started his summer show on Llandudno Promenade in 1864 and a winter show in Liverpool’s Lime Street in 1868, his son Richard Codman II who took over the Liverpool show in 1888 and who always appeared before the public in his grey topper, red scarf, frock coat, checked trousers and spats, and whose younger brother Herbert worked the show at Llandudno until he died in 1961, Richard Codman III whose brother Bert worked in Colwyn Bay and Rhos-on-Sea, and Herbert Codman’s son Jack who took over the Llandudno pitch in 1961. As another Codman, Jack, once said: ‘The Codmans never retire from the show. They transfer from one box to another.’

Punch puppet, Fred Tickner, about 1975. Museum no. S.554-2001. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Another group of Punchmen working in the mid to late 20th century have been called ‘the beach uncles’, performers who have assimilated the traditions of the swatchel omis but who were not part of established Punchmen families, while a third group has been dubbed: ‘the counter culturalists’ - performers who emerged in the 1970s and 1980s and who were drawn to the tradition for its lifestyle and because it offered an alternative to corporate ideology.

Despite academic classifications of the types of Punchmen, every Punch and Judy show had at its heart the same anarchic star Mr Punch with his relentless baton, his annoying baby and wife, and the same knockabout comedy. Many featured the same characters, but within each show there were considerable variations, those of the ‘swatchel omis’ handed down from previous generations, each fiercely proud of its own traditions. Some included ‘turns’ such as the Chinese jugglers who tossed spinning plates from one to the other, the boxing match and a neck-stretching puppet. Some retained a Beadle character, while others had replaced it with a Policeman, but most featured the Crocodile as Punch’s meanest adversary instead of the Devil. Punch and Judy shows are the same but different, their differences reflecting the individualities of their ‘professors’. Nevertheless, all who become adept and strong enough to perform a show that requires the performer to keep both arms up in the air for extended periods of time, alternate voices whilst keeping a swazzle in his mouth, remember a script and which puppet to bring on next, and manipulate objects with the fingers of their puppets above their heads have to be passionate about Punch and his traditions.

Bert Codman’s Punch & Judy booth at Colwyn Bay

Photograph by Dave Williams, 1968. Gerald Morice Collection. Museum no. S.2333-2013. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Professor Richard Codman lll's Punch and Judy booth outside Lime Street Station, Liverpool

Black and white photograph by Waldo S. Lanchester. Gerald Morice Collection. Museum no. S.3481-2013. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Percy Press Senior holding Judy and Baby outside his booth, and Mr Punch in his booth, in front of the crocodile.

Black and white photograph taken in Munich, 1973. Gerald Morice Collection. Museum no. S.3489-2013. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Judy gives Mr Punch the baby to look after. Geoff Felix's Punch and Judy show, May Fayre, Covent Garden, May 2012. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Punch in the 21st century

Mr Punch was in Covent Garden at the restoration of the monarchy in 1662, and he was at the Millennium Dome exhibition in Greenwich in 2000 when Punch and Judy shows played daily. He’s got the hump, and he’s keeping it, despite Punch and Judy shows being identified in a government website as one of the twelve most important British icons including Stonehenge, a cup of tea, Alice in Wonderland and the Routemaster bus. He has a Punch & Judy College of Professors dedicated to his performance, a Punch & Judy Fellowship to bring ‘professors’ together. He’s more about booking than bottling now, and can still be seen around the country delighting audiences at festivals, fetes, shopping centres, holiday parks, schools, parties, corporate events, Christmas Fairs and naturally, the seaside.

Punchinello who Pepys saw in Covent Garden in 1662 can be seen there every May, flouting political correctness and entertaining audiences in the same spirit that he has done for over 350 years. He hasn’t gone far, but he’s come a long way. Now that’s the way to do it!

This expanded content on Punch and Judy, including the accompanying videos, has been supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund via the Big Grin project

Beautiful gifts from the V&A shop

Browse the beautiful V&A Shop for exclusive gifts, jewellery, books, fashion, prints & posters, custom prints, fabrics and much more. All your purchases support the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Shop now