Conservation Journal

Spring 2012 Issue 60

Preserving intangible integrity

Anne Bancroft

Senior Book & Paper Conservator

Although the V&A is a secular museum of design, it does have in its collection objects that were made for religious purposes. In most cases, even within a museum, these objects still retain their sacred importance to people of the religion. In addition, the V&A has objects that are of cultural importance. They do not necessarily have religious origins, but are objects that people may identify with as being symbolic of their particular culture. The Museum has an Access, Inclusion and Diversity Strategy which links directly to government agendas on ‘equality, diversity and social cohesion’, and this influences the work of the conservation department. The diversity emphasis here is on ensuring that all aspects of the V&A - the staff profile, the collections, audiences, programmes and events - reflect the diversity that exists within society, whether in relation to socio-economic and educational background, disability, age, ethnic background, religious belief, and country of origin, residency or sexual orientation. (1)

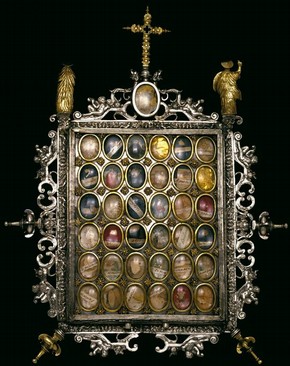

Conservation meets these aims by using the ‘V&A’s Conservation Ethics Check List’. (2) Conservators reflect on why work is being undertaken, its implications now and in the future and the effects of the treatment on the value of the object. This ‘value’ may be of historical, aesthetic and of cultural or faith importance. (3) Conservators, become aware of an object’s cultural or faith importance normally thorough discussions with the curator and their own research, which can include speaking with representatives of the community. Some objects have been identified by communities or a faith group as having significant importance for them. This identification has been added to their museum record, when possible. However, the display and preservation needs of these types of objects were not previously being recorded. Initially, as personal research, case studies of these instances were collected, including Buddhist sculpture, cultural dress, human remains, reliquaries, sacred texts (Korans, Bibles, Torahs) and samurai swords, to name a few (Figure 1).

Respecting objects’ faith or cultural significance can require adapting conservation and display procedures and/or the selection of alternatives to materials and techniques. Sacred relics and paper/textile rolls of written prayers, known as mantra scrolls, are normally placed inside sculptures of authenticated Buddhist deities. In the case of a White Tara sculpture in the V&A’s collection, the scrolls and relics had been removed, possibly in the early 20th century with the mantra scrolls now being stored separately from the sculpture (Figure 2). Through consultation with recognised Buddhist Lamas and Buddhists, there was confirmation that the relics and mantra scrolls are integral to the object and their removal jeopardises the integrity of the sculpture. A recognised Rinpoche strongly advised that they should be replaced. Replacing the mantra scrolls will require substantial resources and further consultation as it is normally done in ceremony by a Lama or Rinpoche. The reintegration of the scrolls has not yet happened but the process has altered our future treatment of similar objects. There is now recognition of the cultural implications of this type of separation.

When working on a Torah scroll, one of our conservators consulted with a curator from a Jewish Heritage institution about appropriate adhesives and consolidants. It was explained that although isinglass, a consolidant and adhesive made from the sturgeon fish, has good conservation properties; it may not be kosher and because of this uncertainty, not appropriate to use on a Torah. In this instance the conservator used methyl cellulose to consolidate pigments. Further discussion highlighted that Torah scrolls are used/displayed upright in a synagogue but when in storage, they can be flat. (4) The Torahs in the Sacred Silver & Stained Glass Gallery subsequently are displayed upright (Figure 3).

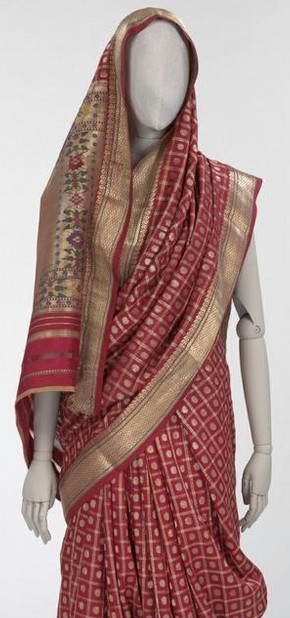

A cultural example was highlighted during preparation for the Maharajahs touring exhibition, when the majority of the saris prepared for the exhibition were displayed in their period and regional style. Consultation with the community was sought for the appropriate wrapping styles (Figure 4). (5) When treating these objects, it can be difficult to identify the most appropriate people to consult in the community. Even in the same community or religion there can be conflicting views. We are in the process of setting up an online resource that will record case studies of objects that have been identified as sacred by communities. We believe this is the first resource of its kind, with the information gained and the contact details with communities recorded, creating accessible contacts and records. It is envisaged that the online resource will initially be used internally but will eventually be shared with, and added to, by other institutions. By sharing and comparing these case studies internationally with other institutions we should be able to share and increase our expertise As government agendas are encouraging diversity and integration in public service institutions, one of the V&A’s objectives is to reflect and engage a wider audience. With one of the most active national and international museum loans and exhibition programmes; lending and borrowing culturally important and sacred objects to and from different cultures will require additional awareness of any sacred or cultural requirements. If the objects are displayed in an appropriate context, the V&A will continue to foster a positive connection with the relevant community.

Conservation has started making visitors aware of how these types of objects are preserved by sharing case studies with intercultural tour guides. Without this, the conservator working on the object would be the only person who knew whether the religious and cultural integrity of the object was considered during conservation. (6) By disseminating and discussing this information we foster collaboration which will benefit both the museums and communities. Museums will gain additional information about its objects, as well as continue to engage different audiences. Communities will engage and form links with institutions that they can refer to for preservation of their own personal and community objects

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sarah Bashir (Conservator V&A) who is currently constructing and designing the database, Sandra Smith Head of Conservation V&A and Crispin Payne, Museums & Heritage Consultant.

References

(1) V&A 2011. ‘Strategy for Access, Inclusion and Diversity’ ./?a=177355

(2) Richmond, A. The Ethics Checklist – ten years on. V&A Conservation Journal Summer Issue 50 (2005) pp . 11-14

(3) Smith, S., Bancroft, A. 2011. ‘Worth a hundred Milibands’; Conservation’s role in Embracing Cultural Identity at the V&A, ICOM-CC 16th Triennial Conference, Lisbon, 19 to 23 September 2011.

(4) Friedlander, E. 2010. Personal communication. Chair of the Czech Memorial Scrolls Trust

(5) Haldane, E-A. 2011. Personal communication. Senior Textile Conservator V&A

(6) Wheeler, M. 2011. Personal communication. Senior Paper Conservator V&A

Spring 2012 Issue 60

- Editorial

- Mahasiddha Virupa: an exploration

- Science Section supports the Public Programme

- REMAI: the European Network of Museums of Islamic Art

- Positive Negative

- Cutting character: research into innovative mannequin costume supports in collaboration with the Royal College of Art Rapid Form Department

- The Alhambra Court fire surround

- Moving Meleager

- Utilising skills and creating opportunities

- Preserving intangible integrity

- Re-housing alabasters: an altarpiece framework mount

- Cinderella table

- Bombay Blackwood

- Punch and Bunny: conservation of a pop-up theatre book

- The technical examination and conservation treatment of Portrait of a Lady by Francesco Morandini

- Conservation of a child’s fairy costume

- Conservation 'on a roll'

- Editorial board & Disclaimer