Disobedient Objects might lead us to reflect on what the future is for art and activism, or what our responsibilities are. In the essay below, artists and activist John Jordan of the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (whose Bike Bloc project is featured in the exhibition) reflects on these questions. The essay was commissioned as part of an exhibition in Manchester, Politika, which coincides with Disobedient Objects and features activist and socially-engaged art projects of various kinds.

Notes on the work of art (and activism) in the age of the Anthropocene

Part I

Over the last decade it has become scientific consensus that this model of society is leading us to a planet whose atmosphere would resemble something in between mars and venus, a place with temperatures similar to hell. The resulting global collapse would make every historical local collapse of civilisation pale into tragic insignificance. Ultimately we are talking about the possibility of the human species becoming extinct over the next few generations.

We have entered an epoch unlike any in human history – the Anthropocene. An Epoch is a geological time period. Named in 2000 by earth system scientists and an atmospheric chemist, the Anthropocene marks an age where humanity has itself become a collective geophysical force of nature. Of course it is not all of humanity that is responsible for ushering in the age of the Anthropocene, the average Bangladeshi consumes 26 times less energy than a Belgian, some of us are more much more responsible than others.

The Anthropocene is an epoch where there are more trees growing in farms than in the wild, where more rock and soil is moved by bulldozers and mining than all ‘natural’ processes combined and where the climate is tipping out of control due to the burning of oil, gas and coal. Industrial capitalism is irreversibly altering the natural cycles of the biosphere, nature is now a product of culture. It is not longer just asteroid impacts and volcanic eruptions that herald mass extinctions, it is us, the 20% of the world that is consuming 80% of it’s resources.

In the age of the Anthropocene the ancient distinction between natural history and human history, between culture and nature collapses. We are woven together, entwined in each others fates. Historian of science Christophe Bonneil describes it as a moment of “all powerful vulnerability.” It is a crisis with consequences whose scale are unimaginable and what this generation is living through is the final confrontation between capitalism’s need for infinite growth and the finite resources of the planet, no amount of financial speculation or high tech invention will buy the system its way out of the inevitable crash. The future is not what it used to be.

“Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself.” wrote Walter Benjamin in his seminal 1936 essay: The work of art in the Age of Mechanical reproduction. “Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art..” In the wake of the advent of film and photography a major change in the structures of perception would arise, suggested Benjamin. In the age of the Anthropocene, many of us are sensing as Ivan Illich called it, “the shadows our future throws,” these shadows are profoundly shifting our perceptions and yet many of our behaviours seems little changed. These notes are a reflection on the role of art and activism at a time when neither seem like powerful enough tools to transform the world anymore and yet transform it we must. They are an attempt to find the shape of hope in the shadows.

I

The first time I sensed the power of art I was seven. My mother took me to a Rene Magritte retrospective. I remember the strange sweet smell of the museum, the peaceful silence and the clouds, lots of them, painted white, fluffy and dream like. But most of all I remember the sense that the images conveyed: the world could be more than just this world.

13 years later I was sitting in university seminar and I had that gut feeling again. I was an art history student and our eccentric bow tie wearing lecturer was reading out the futurist manifesto, gesticulating wildly. At the time I had no idea of the fascist implications of the futurists ideas, but I remember the radicality of their words, the way they cracked open my imagination, I remember the phrase “we will destroy the museums”, and I sensed that there was so much profoundly wrong with the world as it is and that separating art from everyday life was part and parcel of the problem.

Fast forward to 1994, I’m 29, I’m a 0.5 lecturer in fine art, my son Jack had been conceived, and I threw myself into a campaign of direct action against the building of a motorway that would rip a hole through east London, destroying 350 homes and several ancient woodlands to save 7 minutes on a car journey. As I sat on a bulldozer with others, momentarily stopping it tearing up a 400 year old forest, my perceptions of the world are transfigured once again. I realised that activism could become an art work, a form of performance that was beautifully efficient. In a time of crisis art could not be about representing the world any more, but transforming it. Little did I imagine that such art would two decades later find itself enclosed in museums.

II

As I was blocking the bulldozers in London, in Paris, the Grand Palais was holding a gigantic exhibition: Impressionisme, les Origines: 1859-1869. The dates are significant. The first Impressionist show is normally dated April 1874 in Nadar’s studio. What happened between 1870-73? Why did this show’s chronology end in 1869? What history needed to be erased even as recently as 1994?

What happened, was the Paris Commune, an insurrectionary blast that lasted 72 days over the spring of 1871. The rebellion was fueled by the sense that the great revolution of 1789 had been left incomplete. The commune cracked a fault line between the competing forces of the century, it was a fissure between capital and the people, the rulers and the ruled, between those who desired autonomy and those who profited from slavery. What began as a kind of 19th century Woodstock – a resistant festival where bodies reinvented themselves and new forms of life were acted out; ended with the stench of rotting corpses filling the streets of Paris. In the last bloody week of that brief utopian spring, 30,000 protesters were shot dead by a republican government desperate to wipe radicalism from the city of light.

If the commune was one of the first insurrections of the modern era, what objects and artworks did it bequeath to us? There are the hundreds of thousands of posters that plastered the walls. Many were text only communiqué’s that were often transferred to print format within hours of telegraph messages arriving to the printers from across the city and the front lines. The printers were self managing their print works and had the right to read discuss and edit the messages coming in before they went to print and then out onto the streets – it was like an early wiki.

Other art works are the satirical cartoons in newspapers, four thousand lithographs and a handful of black and white photographs where the slow shutter speed blurs any human bodies that are not already dead or posed in complete stillness in glory on a barricade. Their moving bodies become ghostly forms gradually fading into forgetting.

But what were the contemporary artists doing at the time? Most of them, including Manet, Morrisot, Cezanne and Monet, escaped Paris, they took refuge in sea side cottages and rural retreats, most continued painting – portraits, seascapes, silent couples sitting at tables, bunches of flowers…

One artist famously did the opposite, he remained in the insurrectionary city, and put down his paintbrushes, for him; Art was not enough. Convinced that the commune was a prefigurative embodiment of the ideas of his friend and founder of modern anarchist theory Pierre Joseph Proudhon, Gustave Courbet immersed himself in organising. The movement became his material, a kind of prefiguration of 20th century German artists Joseph Beuy’s notions of social sculpture. On April the 30th, Courbet wrote a letter from the liberated city, “I am up to my neck in Politics.. Paris is a true paradise, no police, no nonsense, no exaction of any kind, no arguments! Everything in Paris rolls along like clock-work. If only it could stay like this forever. In short it is a beautiful dream. All government bodies are organized federally and run themselves.”

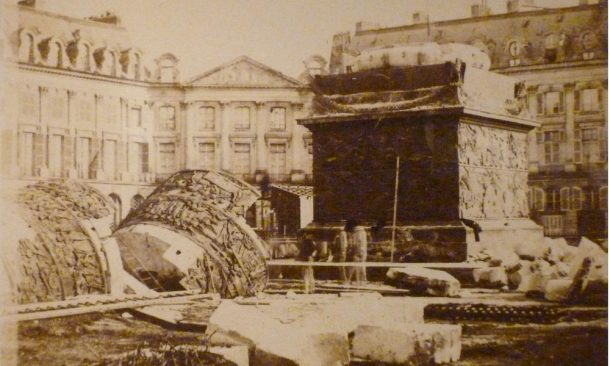

A few weeks later as Marx described, “to broadly mark the new era of history it was conscious of initiating… the commune pulled down that colossal system of martial glory, the Vendome column.” Made from granite and thousands of melted Prussian cannons, with a golden statue of Napoleon in the guise of roman emperor at its summit, this monument to hierarchy and war was incompatible with the solidarity and horizontality of the commune. Originally Courbet wanted to “débouloner” (dismantle) the monument and in a pre-situationist anti-war act of “détournement” re-site it outside the Invalides, the hospital French wounded soldiers retire and recover: “There at least the invalids could see where they got their wooden legs” he wrote.

Despite reservations, Courbet eventually signed the decree for the columns destruction and helped plan the rebellious festival that brought this hated symbol crashing down. The destruction of the Vendome column was a piece of total theatre: Invitations were printed, bands played and twenty thousand people watched as the winches pulled and the column fell engulfing the square in a huge cloud of dust. It was the closing act of the brief utopian experiment and perhaps the commune’s greatest work of art, or rather a work of art after art, the first great performance of artivisme, or neo luddite street art, the world where the spirit of art and activism fuse into one.

The Commune had reduced representation in both its artistic and political form to a minimum, people briefly took back control of their daily life, resistance merged with creativity, alternatives with refusal. The commune heralded what Alan Kaprow one hundred years later imagined the meaning of art might be in the future, “changing profoundly from being an end to being a means, from holding out a promise of perfection in some other realm to demonstrating a way of living meaningfully in this one.”

Six days later the Republican troupes broke through the barricades and began their massacre. The three month long experimentation with new forms of life ended in a week of ruthless killing. Tens of thousands of communards were rounded up, summarily executed or arrested. Marshall law was declared (It lasted till 1876) and the impressionists began to return to town.

Manet, shocked by the repression and critical of what he considers to be the communes ‘excesses’, wrote: “We have all been complicit…This war has ruined me for several years to come.” British travel agency Thomas Cook organised trips to the post commune ruins claiming they rivaled Pompey. Advertising replaced the political posters on the city walls and the communes posters immediately became collectors items.

24 months later in 1874, the impressionists first exhibition opened and it revolutionised painting, but their shock aesthetics simply masked the horrors. It was what today we might call “artwashing”. The slight of hand that transforms ‘radical’ art into a tool for upholding the status quo. On new years eve 1877, Courbet dies in exile, wrecked by debt having been forced to pay 1 million euros for the rebuilding of the column and exhausted from a six month prison sentence.

The Impressionists, ‘painters of modern life’ were radical within the terms of art, they broke the rules of the academy, painted outside and reinvented representation, but in fact their marks were to make us forget.The free and liberated crowd of the commune was erased with portraits of isolated individuals. Streets stained with death were washed away with still-lives bursting with colour. Modern life returned, and with it the myth of the artists as disengaged, ‘neutral’ aesthetic rebel. In Zola’s words an artist who has “achieved perfection” and “arrived at the ideal state”, who “consequently has little care for the world.”

The possibilities of the world were reduced again, a bifurcation closed in on itself. The new forms of social life that arose during the Commune, such as the heated direct democratic debates in the new grassroots clubs, the requisitioned empty buildings transformed into public housing, the expropriated workshops turned into worker owned cooperatives, the demand for female suffrage; withered away like plants brought indoors. Many of these forms would take decades to re emerge, others are still waiting.

From then on progress would be to aspire to an ordered comfortable Bourgeois life. Good furnishings, the smell of freshly cut flowers, the sacred family unit, obedience everywhere. Impressionism had restored the ‘normality’ of modern life. According to art Historian Albert Boeme, modernism was built on the desire to hide the “guilty secret” of the commune. Fearful of taking sides and of getting too close to that which they could not control, the Impressionists had put art in the service of business as usual. The revolting past was given a makeover and moved to the silence of the museum. It’s a lesson for all of us in this moment of transition when we need to give up representation and put art back in the service of life and rebellion.

Commissioned by Upper Space as part of the Politika – Art & the Affairs of the City expo, running 19th September – 1st October. Ancoats, Manchester. Full essay is available online at: www.upper-space.org