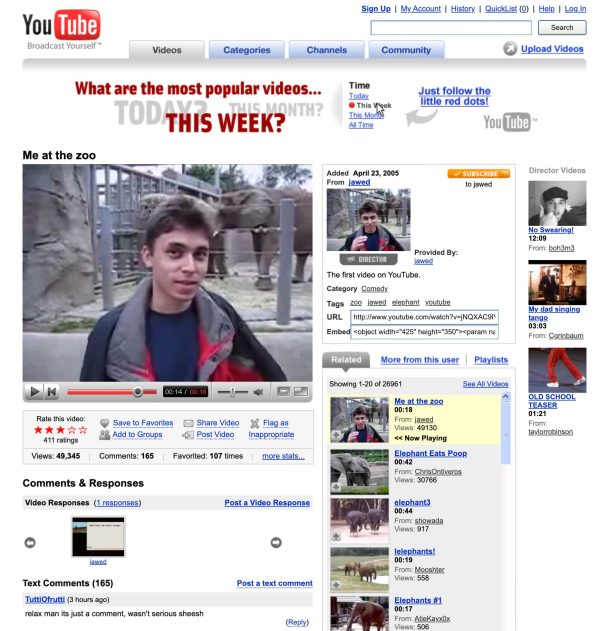

For over a year, a team of curators and digital conservation experts from the V&A, alongside YouTube’s User Experience team, and Interaction Design Studio oio, collaborated on a unique digital design history project. Together, we reconstructed an early watch page for YouTube’s first-ever video, Me at the zoo, using its original source code and the underlying technologies of the mid-2000s.

Imagining YouTube in dialogue with the V&A’s contemporary design collection allowed us to interrogate its evolution and uncover how, despite the tech industry’s characteristic high-speed innovation, the platform’s original ethos still anchors its design today. While its features have vastly expanded since, the foundational design patterns established two decades ago – centered on sharing and watching video while engaging with a global community – remain the core of the platform’s current identity and success. The early interfaces we see in the reconstructed watch page were among the many building blocks that enabled a transformation of the internet around user-generated content.

YouTube is a fundamental example of Web 2.0, the era during which internet users went from consumers to active producers of content. Web 1.0 was characterised by the fact that publishers or content creators were rare, and therefore the web was experienced by most users as a static read-only medium. With the advent of Web 2.0, creation became the new standard. By positioning the upload as a functional counterpart to the download, online platforms redefined the internet’s possibilities as a medium and distribution channel.

This naming convention for the eras of the internet as Web 1.0 and Web 2.0 is a shorthand. The numbering echoes the versioning practices commonly used by software developers. In software, a point release, named for a numbering change after the decimal point, signals a minor or incremental update (e.g., 1.0 to 1.1). A major release, on the other hand, is reserved for a significant update in functionality and is indicated by a shift in digit before the decimal point (e.g., 1.0 to 2.0). Framing the transition from Web 1.0 to 2.0 as a major release might today suggest the existence of an intentional and sudden replacement of the internet’s architecture, rather than a gradual change in how we were invited to use it. In hindsight, this sense of rupture is useful to contrast different web technologies of the time, but in practice, the shift was a continuous and cumulative unfolding of earlier ideas.

In a 1999 article, Darcy DiNucci coined the term Web 2.0 for the first time, arguing that “today’s Web is essentially a prototype – a proof of concept.” The late 90s brought along a sense of optimism and excitement for the internet’s potential to transform all aspects of culture, creativity, and commerce. We owe many of today’s technologies to the early vision of thinkers and developers who were able to look at the early web and see its future promise long before it was technically viable or economically feasible.

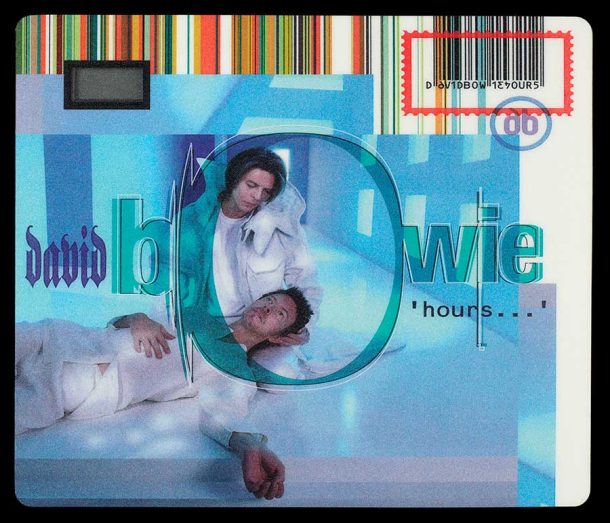

David Bowie’s prescience

Perhaps no one championed this potential more so than David Bowie. In a much-referenced 1999 interview with BBC Newsnight’s Jeremy Paxman, Bowie scoffed at the idea that the internet was merely a tool, remarking:

“I don’t think we’ve even seen the tip of the iceberg. I think the potential of what the internet is going to do to society – both good and bad – is unimaginable.”

Bowie wasn’t just theorizing. He was an early investor in internet technologies and platforms. At the time of that interview, he was already running his own internet service provider (ISP), BowieNet, which gave subscribers groundbreaking opportunities to engage directly with him and other fans, along with exclusive or early access to his content.

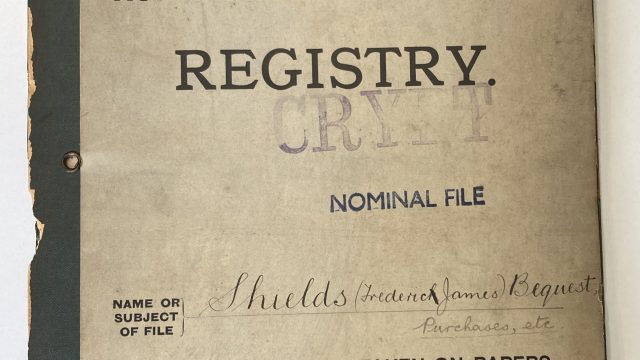

The David Bowie Archive at V&A contains an illuminating array of artifacts, notes, and drawings that capture Bowie’s hands-on approach to the online projects that carried his name. In 1999, he released the album Hours as a digital download before its physical release, which at the time was a radical move for a major artist on a major label.

A year later, he received the BAFTA Berners-Lee Award for the best personal contribution to the interactive industry and the Online Pioneer award at the Yahoo! Internet Life Online Music Awards. Bowie’s role as a digital trailblazer and his legacy of digital projects show his early grasp of the cultural transformations the internet would herald.

Technology as lifestyle

The techno-optimism of the era is most palpable in the marketing campaigns that both shaped and mirrored society’s new attitudes towards technology. The specs inside the hardware ceded ground to the industrial design of these objects and the lifestyle they embodied. IBM, occupying a prominent position in the market since the launch of its first personal computer in 1980, would use the slogan “THINK” to promote its products. As seen in the poster from the V&A’s collection, its brand identity reflected the era’s shift when the ThinkPad – IBM’s business-oriented laptop – was equated to ready-to-wear fashion, pivoting the focus from corporate utility to stylish, portable design.

Coinciding with Steve Job’s return to Apple in 1997, its celebrated “Think Different” campaign can be read as a direct response to IBM’s slogan. Its manifesto and the use of iconic figures of the 20th century, including Amelia Earhart, Muhammad Ali, and Frank Lloyd Wright, was described by Jobs as “[making] it clear to the world (and to ourselves) what Apple stands for.” The campaign cemented the position of Apple as a countercultural, idealistic, and creative company.

The association of lifestyle with technology was not limited to marketing. It physically manifested in peripheral hardware that began to extend the reach of digital technologies into entirely new social and domestic domains. Despite their low-resolution sensors and extremely limited storage capacity, early digital cameras like Apple’s QuickTake 150 hinted at a future of ubiquitous digital media creation. Similarly, disruptions in media access and distribution, fueled by peer-to-peer networks like Napster and the booming availability of MP3 players, showed us how the online world would soon permeate all aspects of our lives. While today we take for granted that the internet can fit in our pockets, these early consumer gadgets are a direct precursor to the always-on connectivity made real by our 21st century smartphones.

Child’s play

Toys often offer, in miniature, distilled versions of the adult world and the values that define a specific era. Think of the model train that captures the kinetic ambition of the steam age, or the dollhouse that serves as a theatrical stage for contemporary domestic life. Understandably, the toys of the late 20th century also captured and mimicked the technological transformations of their time. The Lexibook Junior Powernet 2000 playfully mirrors the interface affordances of internet browsers. Its industrial design echoes the colorful and translucent plastics that at that time signaled to its users that the technologies they encased were fun, creative and approachable.

Tips of the iceberg

It was against this backdrop of technological promise and optimism that Web 2.0 was born. In the V&A’s reconstruction of the 2006 YouTube watch page, we see more than an archival snapshot; we see the culmination of a vision signaled by the digital leaders of the turn of the millennium.

That first YouTube video is perhaps what Bowie predicted: a small, flickering tip of an unimaginable iceberg. As we continue to preserve these digital milestones at the V&A, we invite you to look around at your current digital life and wonder what new developments and technologies will eventually find their place within the museum’s collections as the designed objects of your own era.

Find out more about the acquisition of the YouTube watch page and its first-ever video