Conservation Journal

Autumn 2009 Issue 58 special edition

The Bourdichon Nativity: A masterpiece of light and colour

Figure 1. The Nativity (E.949-2003) (Photography by V&A Photographic Studio)

Figure 2. Lucia Burgio and Richard Hark analysing The Nativity (E.949-2003) by Raman microscopy (Photography by Richard Hark)

In 2003, with the assistance of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, The Art Fund and the Friends of the V&A, the Museum acquired a late fifteenth-century illuminated miniature by Jean Bourdichon, an artist who worked at the French Court and served four kings (from Louis XI to Francis I) in his lifetime.1 The V&A miniature (E.949-2003) is of the Nativity (Figure 1) from the Book of Hours of Louis XII, commissioned to celebrate his accession to the throne in 1499 at the age of thirty-six. The manuscript's troubled history saw it being brought into England, probably at some point in the sixteenth century, where it was eventually debound and its miniatures dispersed among various private collections. It was only in recent times that most of the original miniatures were tracked down again, and within the last thirty years that 11 full-page miniatures, four calendar leaves, and 53 text leaves from the manuscript have been identified; these were the subject of an exhibition at the J. Paul Getty Museum and the V&A in 2005/6.2,3

In spring 2008, the Science Section borrowed, for four months, a Renishaw Raman spectrometer from the Chemistry Department, University College London, with the purpose of analysing as many pieces as possible from the extensive collection of V&A manuscript cuttings (around 2000 items) as well as a series of high-profile medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and miniatures, the Bourdichon Nativity being among the latter. The Nativity was subjected to extensive study by Raman microscopy (Figure 2) as well as X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, the latter by use of an ARTAX micro-XRF spectrometer. Selected areas on the miniature were also examined under high magnification (100x to 800x) with a Leica Aristomet optical microscope. A more detailed description of the results was recently published.4

The results of the XRF investigation revealed that a significant amount of bismuth is present in most grey areas as well as in many brown and black areas, such as in the shepherds peering through the window in the background (Figure 3a&b), the donkey's head and some of the architectural details. The existence of bismuth-based pigments, including those found in other pages of the Book of Hours of Louis XII, has only recently been acknowledged and documented. 3, 5, 6, 7

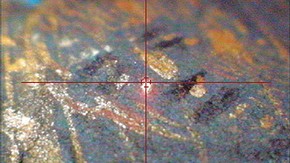

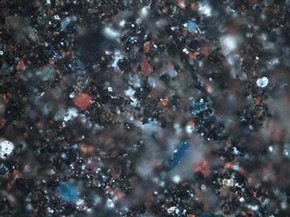

Figure 4. A glittering, iridescent particle in a bismuth-rich area on a shepherd's face. Leica Aristomet microscope, magnification 640x (Photography by Lucia Burgio)

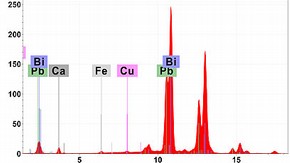

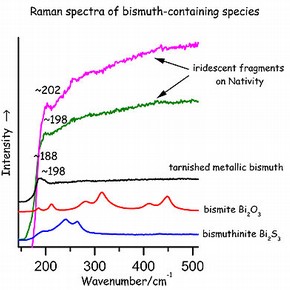

The areas with high bismuth content were examined carefully under high magnification, and a large number of shiny, metallic-looking particles were observed, which were quite flat and very iridescent. The morphology and the appearance of the particles (Figure 4) suggested that they could be either metallic bismuth or bismuth(III) sulphide (bismuthinite, Bi2S3). The yellowish bismuth(III) oxide (bismite, Bi2O3), was excluded as a possibility on the basis of its colour. When the same particles were analysed by Raman microscopy, only a weak spectrum was observed. Reference samples of bismuthinite normally give a very distinctive Raman spectrum, whilst metallic bismuth either yields no Raman spectrum or gives rise to a very weak one, which matched those obtained from the bismuth-rich areas on the Nativity (Figure 5).

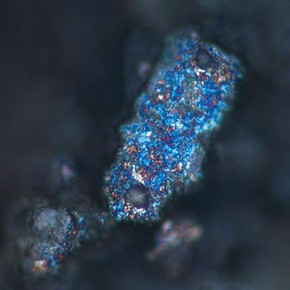

Figure 6. Pigment mixture on the black wooden beam along the PL border of the miniature. Leica Aristomet microscope, magnification 800x (Photography by Lucia Burgio)

The Raman analysis of the various areas on the miniature revealed that Bourdichon used a palette which was rather typical of his time, as traditional pigments such as vermilion, red lead, azurite, indigo, lapis lazuli, lead-tin yellow type I, carbon black, lead white, gypsum, calcite, haematite and goethite were detected. However, these pigments were almost always applied in complex mixtures and it was not unusual to find four or five different compounds used together (see for example Figure 6, showing the colourful mixture used for the black wooden beam along the proper left border of the miniature). These mixtures also included unusual compounds, such as mosaic gold and pyrite, as well as finely divided, more traditional, shell gold. All the evidence collected so far highlights Bourdichon's special ability to utilize conventional and innovative pigments with consummate skill to achieve impressive light and colouration effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark Evans, Merryl Huxtable, Bryony Bartlett-Rawlings and Claire Hart de Ruyter, Victoria and Albert Museum, for their continuous help and support; Mike Rumsey, Natural History Museum, for his advice in matters regarding the mineralogy of bismuth compounds; the EPSRC for a grant for the purchase of the Renishaw spectrometer/laser system; and Renishaw plc for assistance.

References

1. Evans, M., Un Maestro per Quattro Re, Alumina 21, 2008, p. 32

2. Evans, M., Un Capolavoro Ricomposto, Alumina 13, 2006, p. 20

3. T. Kren, T. and Evans, M. eds. A Masterpiece Reconstructed: The Hours of Louis XII, J. Paul Getty and Victoria and Albert Museum (Los Angeles-London, 2005)

4. Burgio, L., Clark, R.J.H., Hark, R.R., Rumsey, M.S., Zannini, C., Spectroscopic Investigations of Bourdichon Miniatures: Masterpieces of Light and Colour. Applied Spectroscopy 2009, 63, pp. 611-620

5. Spring, Marika, 'Black Earths': A Study of Unusual Black and Dark Grey Pigments used by Artists in the Sixteenth Century, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 24, (2003) p. 96.

6. Trentelman, K., Turner, N. Investigation of the Painting Materials and Techniques of the Late-15th Century Illuminator Jean Bourdichon. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy (2009), 40, pp. 577-584.

7. Trentelman, K. A Note on the Characterization of Bismuth Black by Raman Microspectroscopy. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy (2009), 40, pp. 585-589.

Autumn 2009 Issue 58 special edition

- Director's acknowledgement

- Editorial comment - Conservation Journal 58

- Designs on the future: Developing the new Medieval & Renaissance Galleries

- Aspects of the role of Lead Conservator

- Behind the scenes: Conservation and audience engagement

- Medieval & Renaissance Galleries: A passive approach to humidity control

- What's the difference? Climate comparisons for the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries

- A method statement for the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries

- Medieval & Renaissance Galleries conservation progress logs

- New mounts for the headless stone boy and his brother

- Sir Paul Pindar's house on the move again

- Loss compensation at the first floor interior panelling: Sir Paul Pindar's house front

- Training through collaboration - conservation of the Camaldolese Gradual

- A stucco relief by Francesco di Giorgio Martini: Conservation and technical considerations

- The Bourdichon Nativity: A masterpiece of light and colour

- Deteriorated enamelled objects: Past and present treatments

- Stained and painted glass from the Chapel of the Holy Blood, Bruges

- 'This burden of light is the work of virtue': Research on the Gloucester Candlestick

- Digital in-fills for a carpet

- Master Bertram's Apocalypse Triptych: To clean or not to clean

- Professional development in a project culture

- Work in progress: Holbein's drawing processes

- Conservation: Principles, Dilemmas, and Uncomfortable Truths - a summary

- Acknowledgements and Conservation Department staff photograph

- Conservation Department staff chart

- Editorial Board & Disclaimer

- Printer Friendly Version

- Work in progress: the development of the Medieval & Renaissance Galleries