Conservation Journal

April 1997 Issue 23

Editorial - The Raphael Cartoons at the Victoria and Albert Museum

The opening of the Raphael Gallery by Her Majesty the Queen in October 1996 marked the completion of the most recent campaign to ensure that the cartoons are shown under conditions that minimise the risk of damage.

These works were commissioned by Leo X for a set of tapestries, illustrating the lives of St Peter and St Paul, to be hung in the Sistine Chapel. They have enjoyed an almost continuous reputation as great works of art and over the years much thought has been given to their preservation. For instance, when owned by Charles I, copies were made for use at the Mortlake tapestry works so that the originals would not be subjected to hard use by the weavers. Later in the same century a special gallery was built for them at Hampton Court by Christopher Wren; this included a fireplace so that the gallery could be heated to keep the damp at bay.

Their arrival at the Museum in 1865 on loan from Queen Victoria gave rise to extensive discussion about their longterm conservation. This is revealing about the state of knowledge at the time and illustrates how seriously conservation was taken in the early days at South Kensington. In view of the Museum's recent work a revisiting of the surviving papers of 1865 seemed an appropriate topic for an Editorial.

On Friday 28 April 1865 Sir Henry Cole, the first Director of the Museum, noted in his diary with characteristic understatement and conciseness that 'the cartoons came safely from Hampton Court'. He makes no reference to the importance of the cartoons to the Museum nor to the elaborate planning that had been necessary for their safe conveyance.

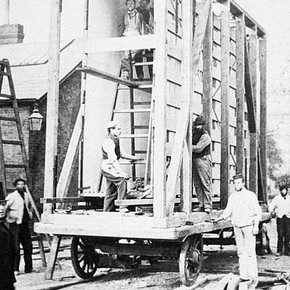

The transport was organised and directed by Captain Fowke of the Royal Engineers and the builder of much of the Museum. So that the cartoons could be removed flat and thereby avoid damage due to folding them, a window was taken out from the gallery. Fowke designed a covered wagon which included a suspension system in order to reduce vibration. It is a measure of the importance attached to the special design of this vehicle that it was photographed at least twice. The whole operation - and a pretty neat one - took 40 men and cost £250.

Opinion within the Museum was not united on the advisability, from a conservation point of view, of moving the cartoons to South Kensington. J C Robinson, the Secretary of the Science and Art Department, had reservations. In his report on the issues he noted that 'the cartoons have for nearly two centuries been preserved under conditions materially different from those they will now be submitted to' and that he felt the conditions at Hampton Court were 'comparatively favourable', in particular the 'minimum of light ... has tended to prevent the fading of the cartoons'. He went on to air his chief worry: 'The cartoons are painted with size or some similar vehicle, which necessarily retains or has a natural affinity for moisture, and would suffer from undue dessication; of all conditions, therefore, that of uniform stagnant, dry, heated, atmosphere would be most inimical, but I fear that the method of artificial heating in South Kensington especially induces these conditions. I believe that the present method of heating by hot water pipes is, generally speaking, bad for nearly all classes of works of art'. Robinson felt open fires or stoves were likely to provide 'equable conditions', though he was keen that the cartoons should be lit by gas light, noting 'the amount of fading from artificial light being infinitesimal'.

Richard Redgrave, the Inspector- General for Art, provided a commentary on Robinson's report and took issue on a number of points. He also wrote his own Report on the State of the Rafaelle Cartoons on their Removal from Hampton Court in April 1865. Redgrave, as Surveyor of the Queen's pictures, had first hand experience of the conditions at Hampton Court. He pointed out that 'The fire was only lighted six days a week, the room being cold and damp and the temperature dangerously low on the seventh'.

Figure 2. Print taken from a glass plate negative with remarks on condition by Richard Redgrave. (click image for larger version)

At Hampton Court, three hazards were highlighted by Redgrave: fire (as the kitchen flues passed under the gallery floor), damp and damage by the visitors (particularly artists making copies). Redgrave had prepared a disaster plan in the event of fire. He had stand cocks installed in the gallery and an 'ingenious but somewhat elaborate machinery' had been devised which allowed the cartoons to be lowered, removed from their frames and folded so that they could be saved. Redgrave recognised however that these careful arrangements were likely to be ineffective in the event of a fire as there was no night watchman to discover one. To mitigate the problems of 'dust and change of temperature' and of the artists, Redgrave had the cartoons glazed which, as he noted, made them into 'mirrors' reflecting the windows of the gallery. He had also had plans to seal the backs with 'painted cloth'. 'It was manifest that he could still less object to the purer air of that Museum, in which, moreover, the light would be carefully regulated, the temperature preserved at an equality, where there are the best provisions against dust, and ample security against any danger from fire, since the buildings are not only constructed as far as possible fireproof, but the police and firemen perambulate the building day and night'.

The final two paragraphs of Redgrave's report discuss the condition report that had been made on the cartoons and the problems of noting 'extensive injuries of a minute nature ... although using photographs as the basis of the registry has been a great aid'. The prints annotated by Redgrave are a remarkable early example of photography being used to document the condition of a work of art.

Redgrave also added some notes for the care of the cartoons when at the Museum. Many strike a note today such as 'The hygrometric state of the atmosphere in the room should be tested from time to time, and its temperature regularly registered night and day'.

The Museum sought the advice of outside experts and Cole noted in his diary the dates of visits by such eminent figures as the art collector, Henry Layard. Charles Eastlake, the formidable Director of the National Gallery, was asked to endorse Redgrave's recommendations, which he did, in particular the proposal that no 'repairs' should be done to the cartoons.

These papers about the forward planning for the transport of the cartoon, the differing views of Robinson and Redgrave, the preparation of condition reports, the consideration of the environmental conditions of the gallery where the cartoons were to hang strike a familiar note. The aspiration of the Museum in 1865 to take the best possible care of these masterpieces of Renaissance Art is one which we have shared in the recent programme of work.

April 1997 Issue 23

- Editorial - The Raphael Cartoons at the Victoria and Albert Museum

- The Prodigal Son: Examination and conservation of a Flemish cabinet on stand

- Traditional practices for the control of insects in India

- Conservation of the 'May Primrose' wedding dress

- Exhibitions: How do they do it?

- The Arundel Society - techniques in the art of copying

- A visit to Liverpool

- RCA/V&A Conservation Course Abstracts

- Printer Friendly Version