Conservation Journal

July 1998 Issue 28

Out of the Frying Pan...

Figure 1. Overall view of Rowntrees Elect Cocoa in studio. (Museum no. E.1209-1927). Photography by Pauline Webber (click image for larger version)

Although no longer a student in a formal sense I am writing in this 'education and training issue' as a recent graduate of conservation training. It will highlight a few of the changes experienced on beginning work in the conservation field after training. I will also discuss if and how these changes can be prepared for, and the (dis)advantages of completing study and entering the 'real world'. Although based primarily and subjectively on my own experiences, and in particular on working for a major exhibition, it will, I hope, also illustrate other more general experiences. It aims to show that there is light at the end of the studying tunnel, even if at times it seems like a train hurtling towards you.

After graduating from the MA Paper Conservation course at Camberwell College of Arts in November 1996, I began working in the Paper Conservation studio at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Employed on a contract basis, mainly to prepare for the present Power of the Poster exhibition, the past eighteen months have been an illuminating, hectic, but ideal insight into working in the conservation world. After studying for a number of years, albeit combined with work experience, the 'real thing' is in many ways a shock that can only be partially prepared for, although I hope that my lack of experience in some areas has not been a hindrance.

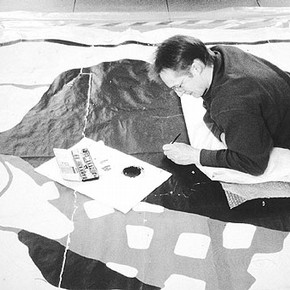

Figure 2. Flattening preparation for lining. Photography by Pauline Webber (click image for larger version)

By the time this article is printed, the Poster exhibition should have been successfully open for a couple of months, yet at the time of writing final preparations are continuing at a frenetic pace. The exhibition explores the strengths that have made posters such a powerful medium, focusing on those produced for performance, entertainment, art, propaganda, social issues and commerce in the last 100 years. Over 350 posters are included all of which have passed through Conservation in the past few months. Full treatment involving surface cleaning, removal of old backings, relining, infilling losses and retouching have been necessary for many, and all have been mounted.

The scale of the exhibition was much larger than anything I had previously been involved with, and due to the size and number of posters, was a major undertaking for the studio. Some are massive paper objects (Rowntrees Elect Cocoa for instance measuring 4x3 metres), which has necessitated a good deal of planning and organisation. The majority of the posters are mounted on fairly substantial supports, the simple handling of which has meant I have had to become a lot fitter and more muscular.

Every aspect of the poster exhibition and its installation have been subject to financial approval. Stressing the importance of gaining a real understanding of costs, both materials and time, would be a valuable element of all conservation training courses. Therefore, although I hate to begin with it, the most obvious issue on beginning work is money. On a self-interested note it is very nice to now get paid, even if it doesn't always feel like enough. My gratitude at being in paid employment however masks an important issue in conservation.

The reliance on volunteers, combined with the expectation that new employees will have x years experience can make graduation a very tough time, especially financially, when you can find yourself undertaking internships or voluntary work with little or no funding. I am increasingly realising that the money issue permeates the whole conservation arena. In an era in which the arts (among other things) have been severely underfunded for many years, the crisis in funding cannot be ignored. Most people are well aware of funding problems, and monetary issues were not irrelevant at college, yet the necessity of budgeting has still come as something of shock when it translates into very real issues in your working life.

Coming from a training course not based in an institution (unlike the V&A / RCA Conservation Course), one of the other immediate issues is how conservation fits into the wider scheme of museology. In contrast to training, conservation is no longer the focus of everyone and learning to work successfully alongside colleagues with different priorities has been interesting, invigorating and at times definitely challenging. Preparing for the exhibition has necessitated liaising with curators, designers and object handlers amongst others. As well as this of course there has been the adjustment needed to settle into a working studio. Training courses make a real effort in parallelling working practices, yet the pressures cannot be simulated. Combined with the 'pressure of perfection' is the 'pressure of time'.

The course at Camberwell included an element on the conservation of 'oversize paper objects' and four posters were researched, documented and conserved by a group of ten students in over two weeks - a luxury now almost unimaginable. Deadlines are tighter and without the elasticity offered to students, the expected output is much higher, and has to be produced in a shorter time. Although the highest standards are maintained, reports are necessarily more succinct - for example producing the fullest detailed documentation of the 300+ posters would have been an unnecessary impossibility. Decision making is one of the most important skills taught during training and should be stressed. Deadlines and workloads mean that a continual reassessment of priorities is necessary as conservation work progresses, and to some degree treatments can be limited by the time available.

Figure 4. Taking it easy...Retouching the poster. Photograpy by Pauline Webber (click image for larger version)

One final point is that as the end of studying grows nearer, you feel that in some way you should 'know it all' and have cracked the secrets of conservation. However, learning doesn't end by any means; if anything you realise how much more there is yet to learn but with less time for research and further study. The Conservation Department aims to provide time and resources for continuing development, yet this is not easy to fit into a full schedule in departments that have high workloads and may be understaffed.

Hopefully this has been a positive comment - the last year and a half has been a largely enjoyable 'first real job' in which I have learnt a great deal from working in a supportive and challenging team environment.

An article detailing the organisation and procedures of the conservation undertaken for the Poster exhibition will be published shortly by Pauline Webber and Alison Norton.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Pauline Webber and the rest of the Paper Conservation studio.

July 1998 Issue 28

- Editorial - Education and Training

- An Exploration of the original appearance of Nicholas Hilliard's portrait miniatures using computer image manipulation

- Outer Limits: The Ups and Downs of Being a Student on a Collaborative MA Couse

- Archaeopteryx - a wing and a prayer

- Internships at the V&A

- Six-month Internship in Decorative Surfaces

- Life as an Intern

- The External Examiner

- Out of the Frying Pan...

- Report of a Research Trip to Tokyo and Kyoto in January 1998 founded by the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation

- Review of 'Care and Preservation of Modern Materials in Costume Collections'- New York 2-3 February 1998

- Printer Friendly Version