Conservation Journal

Autumn 2001 Issue 39

Conservation of a crewelwork bed curtain

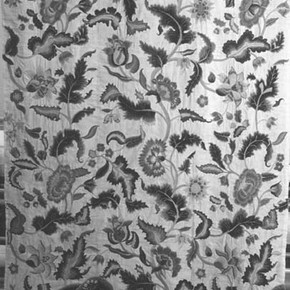

The curtain shown in Figure 1 is part of a set of bed hangings comprising four curtains and three valances. Originally there may have been more pieces in the complete bed set. One of the curtains bears the embroidered date 1755. The design reflects the influences of a flourishing trade with India and is worked in the traditional English embroidery technique of crewelwork, which was popular at that time for domestic furnishings.

The design depicts rolling hillocks with animals, insects and a repeating motif of a hound chasing stag. From the hillocks, branches rise upwards supporting floral motifs. The polychrome wool embroidery is worked on three widths of an off-white linen and cotton 3.1 twill fabric (the ground). The top of the curtain has a band comprising three panels of a linen and cotton fabric in a broken twill weave. Button-hole stitched holes are visible along the very top edge, perhaps for hanging. The curtain has a plain weave linen lining.

Condition before conservation

Before conservation the curtain was in a very poor condition and could not be handled safely. Both the curtain and lining were heavily soiled, yellowed and stained. The crewelwork technique had created disparities of tension and weight between the embroidered areas and unworked ground resulting in puckering and distortion of the ground fabric around the embroidered motifs. This had been exacerbated during hanging, causing the warp threads to split along the embroidery/ground interface in many areas, but most notably the lower half (figure 2). Darned repairs to some of the tears, worked through both the ground and lining in a thick thread, were also producing distortions. Some of the larger holes had been patched unsympathetically and crudely, as had a large rectangular 'window' in the lining. The cut and unturned edges of the curtain had frayed.

The crewelwork embroidery, however, was in very good condition, almost completely intact and unfaded. The only visible repairs were in brown wool in the hillock pattern where probably dark brown or black wool threads had been lost through the deteriorating effects of an acidic tannin used in the dyeing process.1

Treatment

A pivotal decision was whether or not the lining should be removed to facilitate conservation treatments. Removing the lining would make it easier to reduce the puckering and distortion caused by the embroidery, so that any stitched support would be more effective; it would also facilitate the removal of soiling during wet-cleaning. After testing in a range of cleaning solvents2 it was decided to remove the lining in order to wet-clean and re-align the curtain. This could not have been achieved with the lining attached although it meant losing those repairs worked through both layers. The lining did not have enough fullness to provide adequate support and where repairs pulled on the weak ground, the weight of the lining when wet would add even more strain.

Separation exposed large amounts of dust and debris trapped under the lining. Both layers were surface cleaned using low-powered vacuum suction. The lining was treated first. It was wet-cleaned in a solution containing the anionic surfactant Hostapon™ in deionised water at room temperature. Hostapon™ can be used at a low concentration and is very good at soil suspension. A chelating agent, tri-sodium sulphate was added later to encourage soil removal. After rinsing the lining was laid out flat and excess water blotted. The weave was eased into alignment and the lining left to dry naturally. A weak edge and the rectangular hole were given patch supports of a fine linen fabric dyed using Ciba Geigy Solophenyl™ dyes.Further easing out and alignment was done by using an ultra-sonic humidifier to produce cold vapour. The humidified areas were then re-pinned. This was particularly effective and the curtain was noticeably flatter. A fine linen fabric had been dyed and prepared for a full support by marking a grid with tacking stitches. The grid included a one centimetre allowance per thirty centimetres, in both length and width, for ease. Linen was chosen for its ability to creep and mould into the undulations of the curtain.

The support and a few dyed cotton infill patches were correctly positioned and tacked to the curtain in the grid to avoid movement and misalignment during treatment. Herringbone stitches were then worked along the two seam lines for overall support. Some stitches were also worked through the embroidered floral motifs to support their weight. Areas of loss and splits were secured with lines of laid and couched polyester thread. Fraying side edges were overlaid with dyed nylon net before the lining was stitched back on to the curtain. Velcro™ was attached to the reverse top edge for display over a padded mount

Conclusion

The curtain was chosen for the British Galleries as a fine and charming example of English embroidery of the late seventeenth century. Although bright and intact it was visually and structurally marred by soiling, tears and holes. The aim of the conservation treatment was to ensure that the curtain was 'stable, in optimum visual condition and technically understood'3. Separating the layers meant that the treatment could meet those objectives. The bed curtain is now on display in Gallery 56 as an example of 'exotic styles' influencing British design in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

References

1. Tímár-Balázsy, Á & Eastop, D, 'Chemical Principles of Textile Conservation', Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998, p95.

2. Samples of each colour were wet-tested for fastness in deionised water pH5.5; a 0.2% solution of 3.7g/l of the non-ionic surfactant Synperonic N™ and 0.5g/l sodium carboxymethylcellulose in deionised water pH6.5; a 0.25% solution of the chelating agent tri-sodium sulphate in deionised water pH7.0; industrial methylated spirits; Stoddard solvent

3. Umney, N & Oakley, V: 'The British Galleries 1500-1900: An Overview', V&A Conservation Journal 33, October 1999, p5

Autumn 2001 Issue 39

- Editorial

- A concise approach: Managing information for the British Galleries Conservation Programme

- Reverse painting on glass in the British Galleries

- Book display in the British Galleries

- Too big for his boots - Relocation of the Wellington Monument model

- Overview of the gilded objects treated for the British Galleries

- East meets West: The Althorp Triad

- A gun-shield from the armoury of Henry VIII: Decorative oddity or important discovery?

- Conservation or restoration? Treatment of an 18th century clock

- The British Galleries project from a paintings conservation perspective

- Chinese wallpapers in the British Galleries

- Censer: Making Sense of an Object

- Ephemeral or permanent? Illuminating the Bullerswood carpet

- Conservation of a crewelwork bed curtain

- Printer friendly version