Conservation Journal

Spring 2012 Issue 60

Moving Meleager

Roger Murray

Museum Technician

Sophy Wills

Senior Metals Conservator

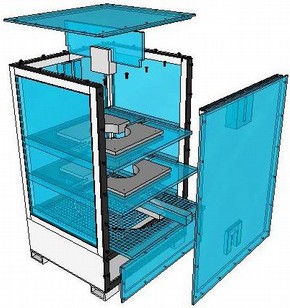

Between October 2011 and July 2012, three of the V&A’s Renaissance bronzes by Pier Jacopo Alari-Bonacolsi (known as Antico) were lent to Antico: The Golden Age of Renaissance Bronzes held at the National Gallery of Art, Washington (20/11/2011 – 08/04/2012) followed by the Frick Collection, New York (1 May – 29 July 2012). One of the bronzes, a partially gilt statuette of the Meleager (A.27-1960) dated around 1484-95, has suffered from a corrosion problem characterised by raised spots on the patinated bronze areas since its acquisition (Figures 1 and 2). The problem is managed by controlling the environment in which the object is housed; by maintaining the relative humidity (RH) below 30%. In order to achieve such environmental conditions during transit and enable monitoring of the object between the first and second venues of the Antico exhibition, it was necessary to construct a conditioned travelling case. Ideally, the object and a monitor would be visible to allow for visual checks of both the environmental conditions and of the object during transit. Discussions between the conservator, curators, scientists and technicians established a design concept which fulfilled these requirements. It was then that the difficult task of translating these proposals into a usable form could begin (Figure 3).

The design process was informed by the techniques devised by Phil Sofer (V&A Museum Technician) to pack the object for a previous loan to Mantua in 2007. The Mantua packing method consisted of a foam core box with a removable front and top. The object was held in place by a series of profiled sliding elements that ran on horizontal runners, similar to a drawer in a cabinet. The sliders were constructed in two parts so that the rear element stayed in the box, whilst the front slid out to allow insertion and removal of the sculpture. Modifications were required for the revised method to allow viewing of the object when packed and to make the crate itself airtight (making the polythene wrapping used previously to seal the foam core box unnecessary).

Figure 2 - Meleager. Detail showing corrosion products underlying patina. Photography by Louise Egan

The obvious choice of material was clear Perspex® for its transparent, inert and strong qualities. It was felt that an un-reinforced Perspex case would be vulnerable to joint cracking or corner damage, so a frame and panel system was designed. An outer framework of 18x18mm aluminium was made with grooves to receive the Perspex panels. The framework was bolted to a lower aluminium compartment that would house the monitor and sufficient molecular sieve to condition the object space (as specified by V&A Conservation Scientist Bhavesh Shah). As with the foam core model, the lid and front of the case were removable but fastened with screws threaded into the aluminium, which was increased in thickness in these areas to avoid the risk that repeated insertion and removal of the screws might strip the limited number of threads. Plastazote® gasketing was attached to the framework to provide an airtight seal.

The construction of the framework was designed to allow the case to be disassembled should any damage occur to a Perspex panel. The 8mm panel edges were rebated, creating a tongue that fitted into the grooves of the aluminium posts and rails. The grooves were situated so that the face of the Perspex came flush with the outside of the framework. An extra 2mm was removed from the panel rebate to create a second groove for silicone sealant application between the frame and panel. The sealant rebate was designed to sit on the outside of the case to avoid any danger of the sealant off-gassing inside the case.

To create the lower compartment, the aluminium L section was mitred and TIG (Tungsten Inert Gas) welded together to form a lipped box which was open at one end. A 3mm aluminium bottom was then welded to this. The compartment was bolted to the upper aluminium framework and an opening cut into the front to create an access panel for the molecular sieve and monitor. A Perspex base, which fitted into the bottom of the framework and rested on the lip of the lower compartment, was cut to support the object. Perforations were drilled to allow air flow between the two areas of the travel case. A hole was drilled into the back corner of the base to accept a brass collar to hold the monitor’s probe. Once installed, the probe could remain in the case as the monitor body can be easily removed from the probe lead to allow for removal during calibration and downloading of information. Finally, a bracket was made to hold the monitor in the lower compartment.

At this point, the case was ready to be tested. It was loaded with two bags of molecular sieve and an environmental monitor and the front and top panel screwed down. The relative humidity inside the case dropped within 3 hours from an ambient level of 60% to 22 %. Data showed that this humidity level remained constant for 10 days, indicating that a sufficient air-tight seal had been achieved.

The final stage was to create fittings within the case to hold the object in place. It was essential that the fittings did not come into contact with the patinated bronze areas because of the fragility of the corrosion spots; therefore only gilded areas could be used to brace the object. Small pieces of spider tissue were used to protect the object from contact with the Plastazote padding. These will be renewed each time the object is placed inside to minimise the risk of folds or crumples abrading the surface.

With the case complete, conditioned and the monitor installed, it was taken to the gallery and the object removed from display and fitted inside the case (Figure 4). The object could then remain in an ideal environment throughout packing and transport.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of the National Gallery of Art, Washington and the Frick Collection, and also colleagues at the V&A who helped with this project, especially Phil Sofer and Bhavesh Shah.

Spring 2012 Issue 60

- Editorial

- Mahasiddha Virupa: an exploration

- Science Section supports the Public Programme

- REMAI: the European Network of Museums of Islamic Art

- Positive Negative

- Cutting character: research into innovative mannequin costume supports in collaboration with the Royal College of Art Rapid Form Department

- The Alhambra Court fire surround

- Moving Meleager

- Utilising skills and creating opportunities

- Preserving intangible integrity

- Re-housing alabasters: an altarpiece framework mount

- Cinderella table

- Bombay Blackwood

- Punch and Bunny: conservation of a pop-up theatre book

- The technical examination and conservation treatment of Portrait of a Lady by Francesco Morandini

- Conservation of a child’s fairy costume

- Conservation 'on a roll'

- Editorial board & Disclaimer