Conservation Journal

July 1993 Issue 08

Hankyu - the final analysis? A new approach to condition reporting for loans

The main challenge facing a Systems Analyst, especially those working in the field of Museum Documentation, is that to those who are not fellow practitioners, documentation is a subject almost totally devoid of interest. However necessary it may be to produce good quality documentation the fact remains that 'doing the documentation' is a museum task that has to be done, and gets done by being shoe-horned into a heavy schedule of other commitments. Sooner or later all Systems practitioners experience the struggle to corral often unwilling and highly diverse personalities into an informed consensus. The battle to introduce logical methods of working against a backdrop of individual perceptions as to why change is necessary at all is an arduous and often protracted struggle. Attempts to standardise documentation, make it relevant to the issue in hand and yet not burden people with overly complicated or extensive recording formats is a Sysiphian task. No sooner is analysis of the relevant systems completed and a format proposed than, typically, the demands for more data fields, rather than fewer usually ensue. Users commonly attempt to circumvent data restrictions by squeezing in any information not apparently solicited in any other available space on whatever form is provided. Alternatively, they submit a home-made form which may bear no resemblance to the 'official' version. A personal conviction that has sustained the effort of standardisation is that documentation is an ambassador for the institution. Presentation and organisation, as well as content, are of especial importance when the document is destined for a foreign country.

In order to lead the User along the path by which experience may inform and enlightens, their wishes are, within reason, granted. Inevitably, the pendulum swings back the other way - and cries of 'too much/long/heavy/detailed!' follow. It is at this point that most analysts would conclude that, despite assertions to the contrary, museum personnel actually feel comfortable with the familiar look and feel of wodges of paper. For, despite an understandable aversion towards bureaucracy and paperwork, there is a deep-seated need to cling to archives of paper and an essential insecurity about letting it go. Why have one copy when you can duplicate it several times (often illegibly) and clutter precious filing space with these totemic offerings to posterity? The answer is 'because we have always done it this way'.

These attitudes are beginning to change in the Conservation Department. The essential truth that less is often more has struck home due to the impact and demands of a multi-venued loan to Japan, referred to as Hankyu, the eponymous department store and first venue.

The process of moving objects outside the Museum carries with it the quasi-legal problems of redress in the event of damage to the item whilst it is away from its parent institution. This requires a means of identifying known and subsequent changes to condition by a method that is sufficiently accurate to identify changes to condition unambiguously and yet not so tediously burdensome as to alienate the personnel responsible for such documentation from performing these tasks adequately.

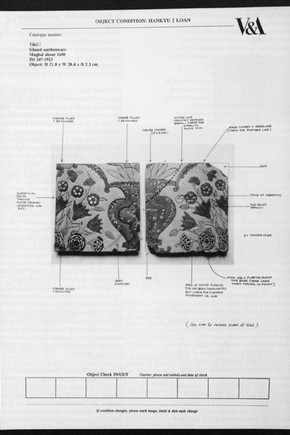

Fig 1. Example of the form used to identify and annotate condition of objects going on loan (click image for larger version)

An initial attempt to produce a satisfactory format, in which the guiding principle of the part of the analyst was that it should be intelligible both in content and process to any courier, from a curatorial or conservation background. Furthermore, it should have only the minimum information relevant to the matter in hand. The form so devised was to be called Final Condition Statement for Outgoing Loans. Interestingly, this proposed minimalist approach resulted in a request from Conservators for a number of data fields that covered object detail, including details of the date of the object and details of manufacturing origin. This immediately indicated that there was a shortfall in the understanding of the suppliers of the information as to its target audience, the object of the exercise and the role of the documentation. A further analysis of the situation revealed that the root cause of this phenomenon lay in an imperfect understanding of the roles and responsibilities of all the agencies involved in the system by which loans are co-ordinated and documented - namely the Loans Unit, the Registrar and the key curatorial staff involved. The conservators assumed that they were creating documentation for themselves, rather than for others to use. Once this had been recognised the foundations existed for a better evaluation of the way in which intentions and needs were signalled between the agents involved. As a spin-off, a new Loans procedure was initiated. But this experience also posed interesting questions about the 'ownership' of information and the willingness, or otherwise, of people to share information in a way that empowered others in the use and understanding of specialised terms and the basis upon which judgements are made. There must be recognition that there are points where responsibilities shift across system boundaries, and that 'rights' also carry responsibilities to be discharged. Systems involving information-sharing place an even higher premium on co-operation.

Eventually, the then version of a Final Condition Statement, one per object, was dispatched to Japan. Accompanying each report was an illustration of the object using everything from hand-drawn sketches (ranging from the good to the more challenging) to photographs - again, either of an acceptable quality or a number of polaroid snaps distinguished largely by murk and bulk. The intention was that the courier checked the item against the condition statement at each unpacking and repacking episode, as well as during the period of display in the case of particularly sensitive items. Any change in condition was to be signalled in an amendment of the text and illustration as and when necessary. It quickly became apparent that the system was unwieldy, requiring an unrealistic degree of manual dexterity to locate and manage records comprising several pages, each containing a significant number of data fields. In short, the whole procedure was burdensome and time-consuming. By contrast, the Japanese approach to the challenge of speedy and satisfactory documentation of changes to condition was elementally simple- a large scale (A3) format diagram or illustration upon and around which comments could be recorded.

It helped that conservators themselves had an opportunity to assess the value of this approach by first-hand experience of the real circumstances under which changes had to be noted. It is often essential in designing systems that users have or acquire some ability to project forward into a theoretical understanding of how things might work in practice. It is this inability to leap that divide in the imagination that so often leads to a disastrous mismatch between perceived needs and practical solutions.

So where has this left us? We have arrived at a compromise between the almost entirely visual record and the heavy-weight documentation side. The result is an A3-sized card upon which a single, or several smaller shots, of the object are mounted. A successful medium for colour reproduction of the items appears to be the colour photo-copying of images originally recorded on 35mm colour-transparencies. This offers the advantage of allowing a good-quality, compact and lightweight original to be stored for reference, and avoids the necessity to produce heavy, bulky, expensive and often slow to materialise photographic plates. An important additional aspect of using the photocopy is that the paper is more receptive to annotation, whereas the surface of a photographic plate tends to repel most marking media.

For me, as Head of Documentation in the Conservation Department, it represents the best yet example of an adaptive response to needs. User involvement and experience is vital in the production of systems; without the practical testing of the original proposal by users, this more appropriate method of addressing the issues of loans documentation would never have come about.

July 1993 Issue 08

- Editorial

- Polychrome & petrographical analysis of the De Lucy effigy

- Protecting Tutankhamun

- Conservation department group photograph, 1993

- Hankyu - the final analysis? A new approach to condition reporting for loans

- Camille Silvy, 'River Scene, France'

- A conservation treatment to remove residual iron from platinum prints

- Film '93: a visit to BFI/NFTVA J Paul Getty Jr conservation centre, Berkhamsted

- The class of '93