Closed Exhibition – Pearls

Pearls: About the Exhibition

21 September 2013 – 19 January 2014

V&A and Qatar Museums Authority exhibition

Introduction

Pearls are a worldwide phenomenon going back millennia. Fascination for these jewels of the sea transcends time and borders. Natural pearls have always been objects of desire due to their rarity and beauty. Myths and legends surrounded them, chiefly to explain the mystery of their formation. Goldsmiths, jewellers and painters exploited their symbolic associations, which ranged from seductiveness to purity, from harbingers of good luck in marriage to messengers of mourning.

Wonders of nature

Shells have been revered as miraculous creations of nature and appreciated for their decorative character. Global exploration led to the enthusiastic collection of shells as rare treasures of exotic lands often displayed in cabinets of curiosities to delight and impress. Later the natural world grew increasingly scientific, and shells were recorded in richly illustrated volumes.

In recent years, the focus of scientific scrutiny has been the pearl itself and its formation. X-ray images have revealed how natural saltwater pearls are formed by the intrusion of a parasite such as a worm or piece of sponge into the shell’s mantle, the organ which produces nacre (mother-of-pearl). The parasite displaces cells to form a cyst, over which the nacre grows.

In principle any mollusc with a shell can create a pearl, from the giant clam to the land snail. The variety of colours and shapes of pearls is unimaginable, ranging from the exotic pink conch pearl, the brown and black pearl, the blue-green abalone pearl and the Melo pearl with its orange hues.

Abalone shell (Haliotis iris) with a mabe pearl in the shape of a worm

Abalone shell (Haliotis iris) with a mabe pearl in the shape of a worm

New Zealand

© Christian Creutz, photographer

Trapezium horse conch shell with pearl (Pleuroploca trapezium)

Trapezium horse conch shell with pearl (Pleuroploca trapezium)

Philippines

© Christian Creutz, photographer

Cymbiola imperialis shell with natural pearl

Cymbiola imperialis shell with natural pearl

Philippines

© Christian Creutz, photographer

A rare selection of natural pearls from the Qatar Museums Authority Collection

A rare selection of natural pearls from the Qatar Museums Authority Collection

© Christian Creutz, photographer

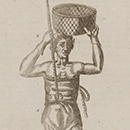

Pearl divers holding onto the rope attached to the collecting baskets, reproduction of original photograph. © Qatar News Agency Archives

Pearl fishing in the Gulf

Natural oyster pearls were fished in the Gulf from as early as the first millennium BC until the decline of the trade by the mid 20th century. The procedure of harvesting oysters has remained unchanged over centuries. The diver’s equipment was basic, a loin cloth, nose clip of tortoiseshell or wood and a leather sheath to hold the oysters.

The diver descended with two ropes: one attached to a net for collecting the oysters (about twelve per dive), the second attached to a stone weighing five to seven kilograms to speed up descent, with a loop for the diver’s foot. When he was ready, the puller attentive to his signals would let the two ropes run free. Within seconds the diver would reach the bottom, sometimes as deep as 22 metres, and let go of the rope carrying the weight.

Little do the magnificent necklaces of natural Gulf pearls, arranged according to scale and lustre, reveal the effort it takes to assemble such masterpieces. 2000 oyster shells need to be opened before finding a single beautiful pearl.

Click here for a map of pearl fishing in the Gulf

Pearl fisher

Pearl fisher

Printed in Museum Museorum by Michael Bernhard Valentini

Published by Johann David Zunners

Frankfurt

1714

© Victoria and Albert Museum, LondonThis is the oldest accurate portrayal of an oyster fisher from the Arabian Gulf.

Pearl fishing in the Caribbean from Les Grands Voyages, published by Theodor de Bry

Pearl fishing in the Caribbean

from Les Grands Voyages, published by Theodor de Bry

Engraving

Germany

1590

© Christian Creutz

Necklace with five graduated strands, Cartier, France, 1930-40, platinum, diamonds and natural Gulf pearls. Qatar Museums Authority. Photo © Sotheby's

Pearl trading in the Gulf

The trade in pearls played an important role for countries along the coast from Saudi Arabia to Dubai, especially Bahrain and Qatar. Seafaring Arab merchants travelled across the Indian Ocean as early as the seventh century, stopping at various ports along the coasts of India and trading with pearls. Merchants from China travelled to India to acquire the highly prized natural pearls from the Gulf, while at the same time Arab merchants expanded their trade network to South East Asia.

By the early 19th century the Gulf was the major global supplier of natural pearls. Demand reached unprecedented heights as high quality ‘oriental’ pearls were much sought after by the great jewellery houses of Europe. The golden age of Gulf pearls was between 1850 and 1930. Today the natural pearl has become a rare gem.

Pearls and pearl necklaces from the Arabian Gulf

Pearls and pearl necklaces from the Arabian Gulf

Reproduction of original photograph

The Arabian Gulf

20th century

© Hussain Alfardan Archives

Cloth bag (dasta) containing merchant paraphernalia

Cloth bag (dasta) containing merchant paraphernalia

Reproduction of original photograph

The Arabian Gulf

20th century

© Hussain Alfardan Archives

Chest belonging to a pearl dealer

Chest belonging to a pearl dealer

About 1920

Wood, brass, agates, paper and textile

Hussain Alfardan Collection, Doha

Lover’s Eye brooch, England, 1800-20, gold, pearls, diamonds and painted miniature. Museum no. P.56-1977, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Pearl jewellery through the ages

Across the Roman Empire jewels with pearls were a desirable and expensive luxury, a symbol of wealth and status. In medieval Europe pearls appear as symbols of authority on regalia, and as attributes of Christ and the Virgin Mary in jewellery, symbolizing purity and chastity. By the Renaissance, portraits show that nobles and affluent merchants were adorned with pearls, the symbolism became increasingly secular.

By the 17th and 18th centuries pearls had become lavish adornments, often worn in a seductive manner. They were also demonstrations of high social rank. By the early 19th century pearls embellished more intimate or ‘sentimental’ jewellery to convey personal messages celebrating love or expressing grief.

The opulence and ceremony enjoyed by the courts of Europe in the 19th century was favourable for pearls, necklaces of all lengths were fashionable, from long ropes to chokers.

In Paris, jewellers working in the Art Nouveau style were fascinated by the extraordinary shaped pearls and transformed them into breathtaking interpretations of nature.

In the ‘Roaring Twenties’ urban life changed fashions, women wore short sleeveless slim-line dresses and pearl sautoirs dangled down to the waist and beyond.

Pair of earrings

Pair of earrings

Roman Empire (Egypt)

AD 100-200

Gold and pearls

Museum no. M.10 & A-1966

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Cross pendant

Cross pendant

Germany

1500-40

Gold, rubies and pearls

Museum no. M.74-1953

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Bodice ornament

Bodice ornament

Spain

About 1670

Gold filigree with freshwater pearls

Collection of Deborah Elvira

Photo © Martin Vellón

'Forget-me-nots' tiara, designed and made by Paul Gabriel Liénard (born 1849)

'Forget-me-nots' tiara

Designed and made by Paul Gabriel Liénard (born 1849)

Paris

About 1905

Horn, gold, diamonds and pearls

Qatar Museums Authority

© Albion Art

The Rosebery Pearl and Diamond Tiara, London, 1878, gold, silver, diamonds, natural bouton pearls and natural drop-shaped pearls. Qatar Museums Authority. Photo © Christie's

Authority and celebrity

In the East and the West tastes in jewellery may vary but the significance of pearls remains the same, with pearls worn as symbols of power and an indicator of rank in society. They were much revered objects of desire due to the rarity of natural pearls.

Rulers wore crowns adorned with pearls to demonstrate dynastic authority and the prosperity of their lands. In Russia, Iran, China and India, ostentatious displays of pearls formed an integral part of the regalia of ruling monarchs.

In Europe, royal and aristocratic women wore rare pearls mounted on splendid tiaras to dazzle and impress. As old social conventions were overturned, pearls adorned the necklines of ladies of fame and fortune. The screen goddesses of Hollywood movies and, more recently, fashionable, media-friendly celebrities have helped to uphold the unfailing glamour of pearls.

Icon with Virgin and Child by Ivan Nikolaev Mnekin

Icon with Virgin and Child

Ivan Nikolaev Mnekin

Moscow, Russia

1886

Gilded silver, painting on metal, enamel and Russian freshwater pearls

Qatar Museums Authority

Photo © Sotheby's

Imperial Court Robe

Imperial Court Robe

China Qing dynasty, about 1870-1911

Embroidered silk, silk and gold threads, corals and pearls

Museum no. T.253-1967

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Drawing of a court necklace worn by the Emperor

Drawing of a Court Necklace worn by the Emperor

China

1750-66

Ink and colour on silk

Museum no. 827-1896

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Sash clip ‘Yaguruma’ (Wheels of Arrows) and box, Mikimoto, Japan, 1937, platinum, 18 carat white gold, cultured Akoya pearls, diamonds, sapphires and emeralds. © Mikimoto Pearl Island, Japan

Origins of the cultured pearl

Attempts to produce pearls through human intervention go back centuries. The ancient Chinese had discovered how to create a blister pearl by inserting an object into the oyster. In the 18th century the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus experimented in a similar way.

However, it was Kokichi Mikimoto (1858–1954) in Japan, who at the beginning of the 20th century was granted a patent for developing round cultured pearls from Akoya oysters that their industrial production began. By the 1950s cultured pearls had conquered the market and Mikimoto’s dream ‘to adorn the necks of all the women of the world with pearls’ became a reality.

Today Mikimoto is renowned for its quality control, following the founder’s philosophy of using only the very best quality pearls for jewellery. Its flagship store is still in the Ginza district of Tokyo.

Sash clip, 'Cherry Blossom' by Mikimoto

Sash clip

'Cherry Blossom'

Mikimoto

Japan

About 1910

15 carat gold coated with platinum, cultured half pearl, small natural pearls and diamonds

© Mikimoto Pearl Island, Japan

'Gothic' choker by Mikimoto

'Gothic' choker

Mikimoto

Japan

2011

18 carat white gold, diamonds and Akoya pearls

© Mikimoto Pearl Island, Japan

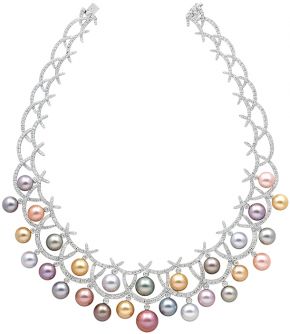

Necklace from the Carnevale Collection, made by Yoko, London, 2013, 18 carat white gold, diamonds, natural colour pink and orange freshwater pearls, golden Indonesian South Sea and white Australian South Sea pearls, grey and blue Tahitian pearls. © Yoko London

South Sea pearls

Cultured pearls from the South Seas are found in countless colours. Their iridescence and hue are dependent on the type of molluscs they are grown in and where they are farmed.

The queen of all oysters, the Pinctada maxima, produces the finest South Sea pearls. These come from established farms in Burma, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and along the northern coast of Australia. The common Pinctada maxima produces white pearls, the silver-lipped variety results in pale metallic-grey tints and the gold-lipped specimen creates gems with an intense golden hue.

The Pinctada margaritifera, the black-lipped oyster from the Pacific atolls, produces the famous Tahitian pearls. These are not all black. Some are white, and the black ones take on spectacular green, blue, even aubergine, tones reminiscent of the colours of peacock feathers.

Melo and brown diamond earrings, made and designed by Hemmerle, Munich, Germany, 2001, rose gold, red gold, pave-set fancy brown diamonds, melo pearl bouton and melo pearl drop. Private Collection. Courtesy Hemmerle

Contemporary design

Jewellery design experienced great changes during the second half of the twentieth century. During the 1960s and 1970s avant-garde jewellers in Europe broke away from traditional gem-set jewellery to create abstract sculptural designs with unconventional settings for pearls. In contrast, the high-end jewellers sought a path between tradition and Modernism. From the 1980s, the emphasis for artist jewellers has been less about the value of the pearl and more about novelty of design. Searching for new ways of wearing pearls, they set them in a variety of metals, often with textured surfaces and successfully combined them with non-precious materials.

Today the range of aesthetics in pearl jewellery is boundless and the variety of pearls quite remarkable. Whether natural, cultured or imitation, pearls continue to be fashionable and are being worn by increasing numbers of women. Pearls are a symbol of femininity and timeless jewels befitting at any event or occasion.

'Grand Jeté' brooch, made and designed by Geoffrey Rowlandson (born 1931)

'Grand Jeté' brooch

Made and designed by Geoffrey Rowlandson (born 1931)

London

1999

18 carat gold, brilliant-cut diamonds and cultured baroque pearls

Private Collection

© Geoffrey Rowlandson

Snow White Wrist Piece 'A Fusion of Winter Snow and Spring Flowers', made and designed by Nora Fok (born 1952)

Snow White Wrist Piece 'A Fusion of Winter Snow and Spring Flowers'

Made and designed by Nora Fok (born 1952)

London

2012

3-D printed white plastic, cultured white pearls

Private Collection

© Frank Hills, photographer

Brooch, made and designed by Friedrich Becker (1922-1997)

Brooch

Made and designed by Friedrich Becker (1922-1997)

Düsseldorf, Germany

1962

18 carat white gold, 96 natural pearls in varying shades

RSV Collection

© Frau Hilde Becker

Interactive Map

Discover the many treasures in the beautiful V&A galleries, find out where events are happening in the Museum or just check the location of the café, shops, lifts or toilets. Simple to use, the V&A interactive map works on all screen sizes, from your tablet or smartphone to your desktop at home.

Launch the Interactive Map