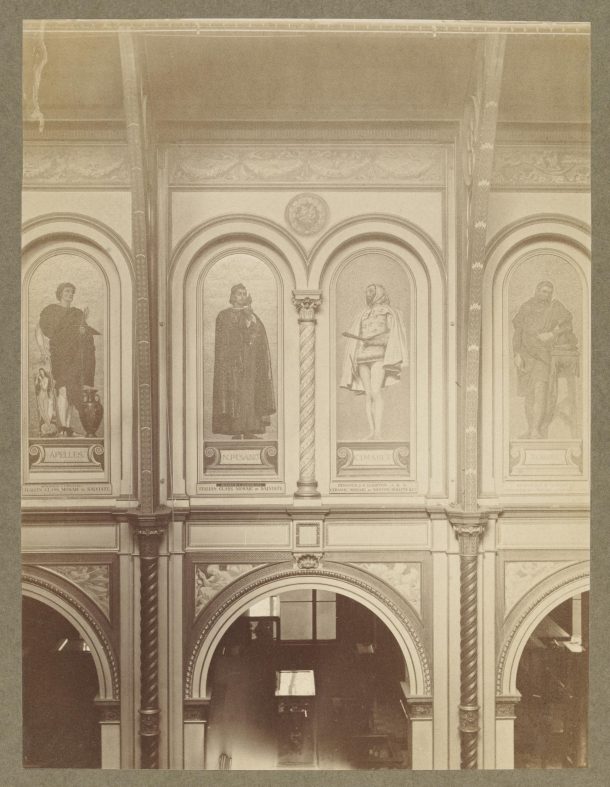

With the Blythe House decant work now in full swing and Conservation and Technical Services carrying out essential remedial treatment and prepacking of the most fragile objects, some are throwing up unexpected and exciting challenges for the team. The ‘Kensington Valhalla’ is a collection of thirty-five mosaics commissioned by Sir Henry Cole, the Museum’s first Director, to adorn the Victoria and Albert Museum walls. They were made to fit into the arcade niches that ran around the upper level of the South Court, which opened in June 1862 (Figure 1). Featuring a series of life-size portraits of famous artists, they were executed in mosaic from either glass, ceramic or painted enamel. Mosaic was used extensively for floors and panels of wall decoration at the Museum. The paintings made as full-scale designs for these mosaics are displayed in various locations in the Museum including The Lydia and Manfred Gorvy Lecture Theatre on Level 4 , the staircase to the west of the Grand Entrance on Cromwell Road, and the National Art Library Landing, Room 85. The mosaics themselves remained in place in the South Court until 1949, when they were taken down and stored. Some are now on display in other galleries of the Museum. This article addresses the approach undertaken to stabilise, move, pack and store these unique objects in a streamlined and non-invasive way.

In early 2019, Technical Services were given the task to develop and implement a new innovative way of handling and packing these unique and somewhat complex objects. There are currently twenty-two mosaics stored at Blythe House that are companions to the others that remain on display in South Kensington. The main challenge was to produce a high-quality storage and transport solution for the un-crated mosaics, enabling the transport company to move them to the new Collection and Research Centre with ease. The project was very much a collective effort with Sculpture Conservation, who ensured that the ceramic and glass mosaics were all stabilised before the team moved any of the objects. The structural integrity of the objects was of the utmost importance throughout every phase of the project.

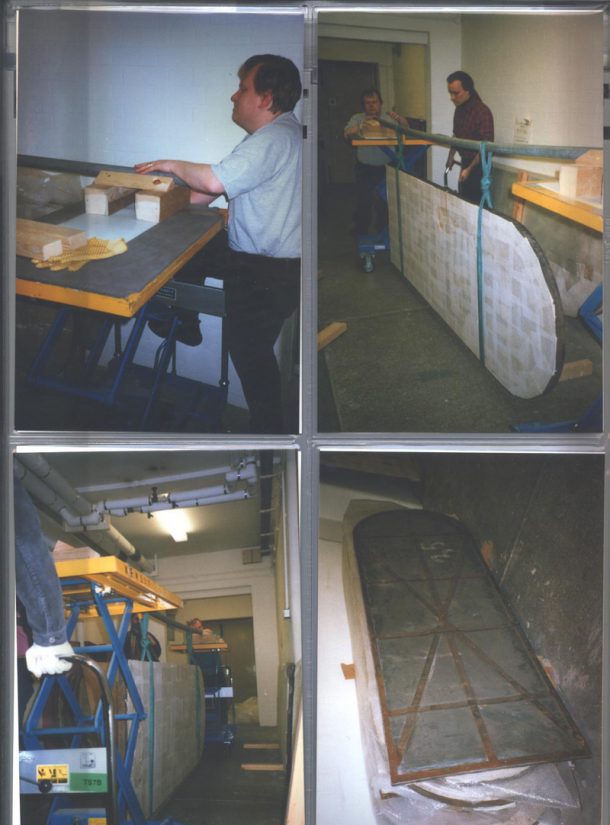

It was decided early on that a new lifting method was essential to move these unique objects that each weigh between 200-400 kilograms. Manual lifting was not a viable option and after much deliberation, Conservation and Technical Services decided on a tried and tested method of two high lift tables, a scaffold pole and slings (Figure 2). This enabled the team to lift these niche objects while reducing the risk of physical injury and avoiding any additional pressure to the object itself. After some research through archived projects, it was revealed that the same method was used over twenty years ago (Figure 3). The team were in a unique position to be able to develop methodologies used in the past and learn from the Technicians who had moved them many years before.

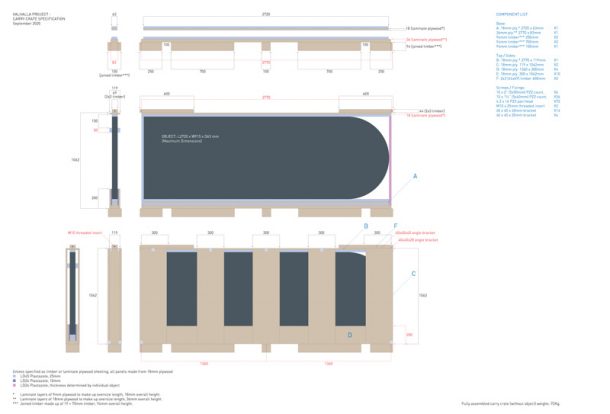

A series of detailed technical drawings were produced incorporating the outline of the Valhalla reproduced to scale (Figure 4). Care was taken to ensure the new crates were able to brace the front of the mosaics without too much additional pressure to the object. Each crate was built around the elevated Valhalla, ensuring that each panel of wood hugged the mosaic without unnecessary pressure but retaining just the right amount to mitigate any potential vibration during the journey to the new Collection and Research Centre in East London. Due to the weight of each object, a layer of plywood sandwiched between two layers of Plastazote foam was required to add buoyancy to the bottom edge of the object, avoiding the chance the mosaic would sink into the foam over time and reducing the further risk of damage during movement and handling.

A pivotal decision about the transportation of the ‘Kensington Valhalla’ needed to be made at the design stage, as this would ultimately affect the way in which they were accessed in the future. The ideal solution was for the objects to be transported within the crate so that the surrounding crate would also act as a means of transport protection, simplifying the storage design. Moreover, individual panels could be removed, alleviating the need for the removal of the mosaics entirely from their crate. This supports any future conservation assessment and treatment processes, allowing them to be as streamlined as possible, while critically minimising any potential risk to the objects in transit.

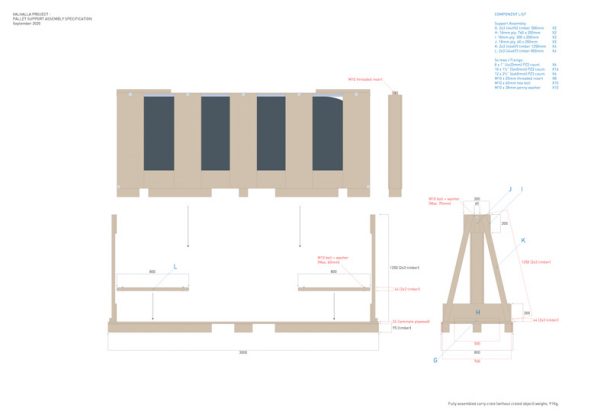

When starting any decant project, the intention is that all the objects go straight into their new storage facility, preferably occupying the same footprint. One problem encountered was the unavoidable storage growth once the Valhalla were individually packed. As they were previously un-crated their storage footprint was minimal. This was overcome by designing a crate that housed the mosaic on its side, closely encased by plywood panels. The new slimline crate design allows for compact storage for such large and heavy objects. Specialised pallets have been constructed for the transport of the packed crates. Designed with a larger footprint, the pallets use timber bracing to stabilize the packed mosaics during transit (Figure 5). Once transported, the crate is removed from the bespoke pallet and stored.

The ‘Kensington Valhalla’ is an integral and infamous part of the V&A’s building history and it is very satisfying to see these incredible examples of Victorian decoration stored in a safe and sustainable way. For the Technical Services team, this project embodies a significant advance in crating objects of this form, merging methodologies used in the past with new innovative packing solutions.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to James McNeff for his immaculate design and contribution to this unique and important project and Adriana Francescutto Miró for her ongoing conservation support.