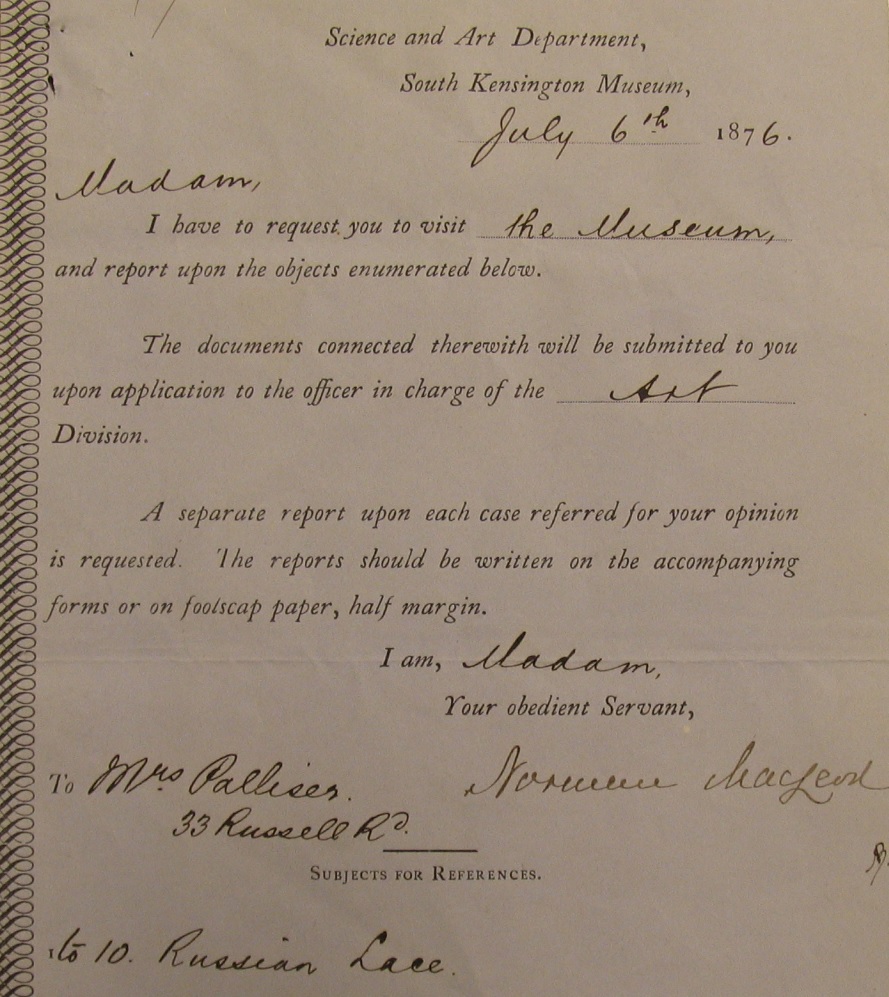

The V&A Archive has just completed a project to catalogue to item-level the contents of 51 boxes of Art Referee Reports. Now we can help museum staff and researchers find provenance information for objects acquired by the South Kensington Museum from 1863-1886. We plan to make the catalogue available online later this year.

What are Art Referee Reports?

In the first decades of The Victoria & Albert Museum’s history art referees were tasked with buying and borrowing objects for display at the museum. A who’s who of the Victorian art world judged artefacts on whether they would contribute to the museum’s collections under qualifying factors: outstanding beauty, rarity of existence, and use as learning tools for students.

The term was first established in February 1857, when Richard Redgrave and Lyon Playfair were appointed ‘Art Referee and Inspector-General of Art Schools’ and ‘Scientific Referee and Inspector-General of Art Schools’. In 1863 John Charles Robinson, then the Keeper of the Art Collection, was appointed the second art referee.

Reflecting on the period in 1897, Robinson wrote that he embarked on ‘successive yearly expeditions, of several months’ duration, in which innumerable art auctions, dealers’ gatherings, old family collections, convent and church treasuries, yielded up an infinity of treasures, usually, as the label prices attached to the specimens at South Kensington attest, at fractional prices as compared with their present values.’(1)

An official record stated that an art referee’s duties were:

‘1. at home and abroad to recommend purchases or loans;

2. when directed, to negotiate purchases;

3. to report forthcoming sales in due time and indicate desirable purchases;

4. to report in writing, when required, on preservation and arrangement of Art Museum;

5. to furnish written descriptions of objects;

6. to attend Board when summoned;

7. not to give daily attendance or keep diary, except when claiming travel expenses; must have written authority for these; send monthly report of proceedings; all communications with him to be in writing; 8. to receive salary of keeper, but not allowance for house;

9. Will compile catalogues when required, and be paid 1l. 1s per page’

(Board Minutes of the Science and Art Department Vol. l I 1852-1863, V&A Archive ref. ED 84/35)

The system of art referees was finally abolished in 1913, when it was replaced by an Advisory Council.

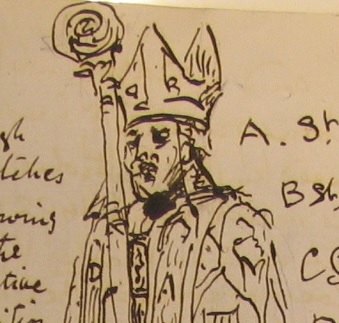

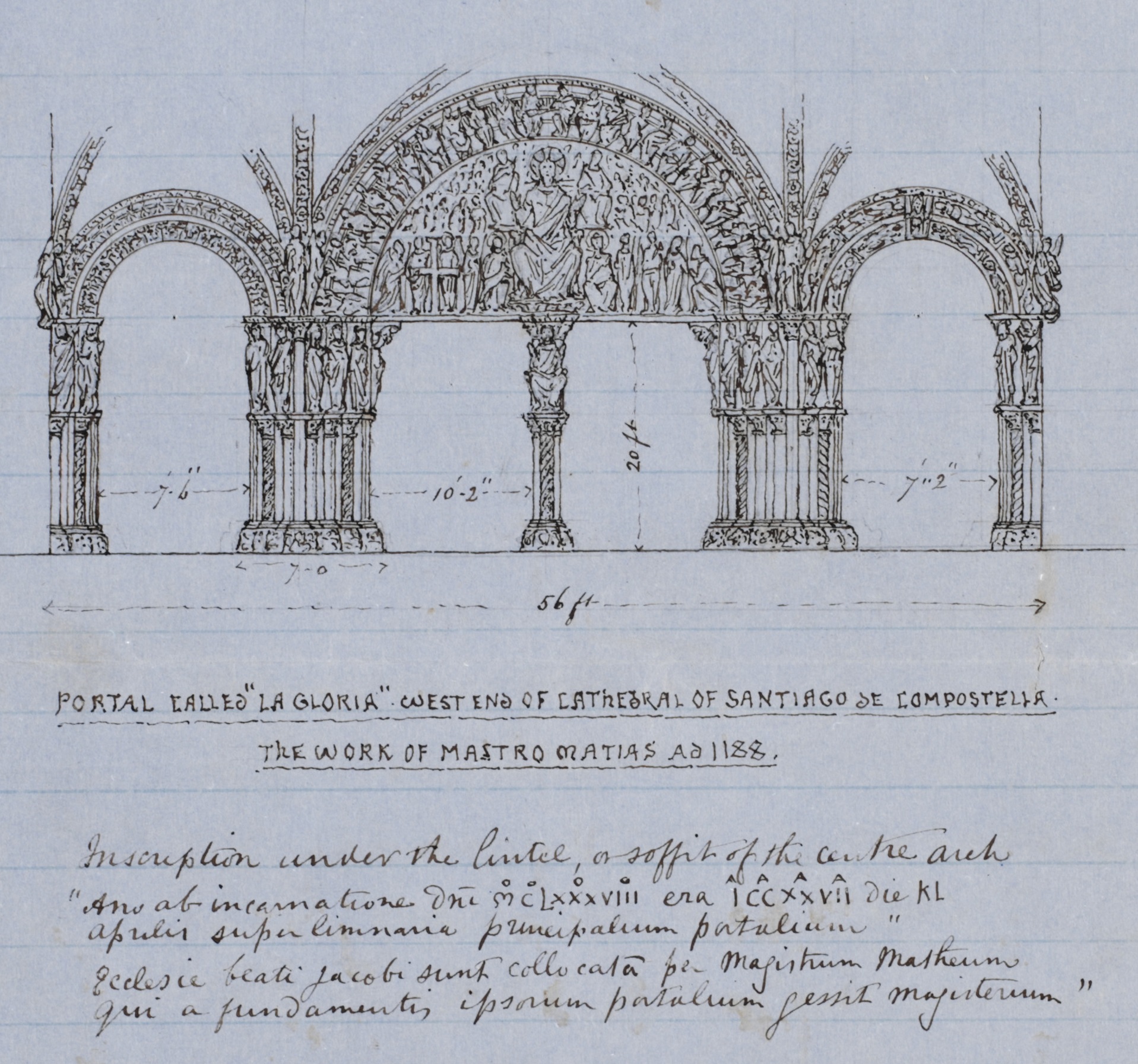

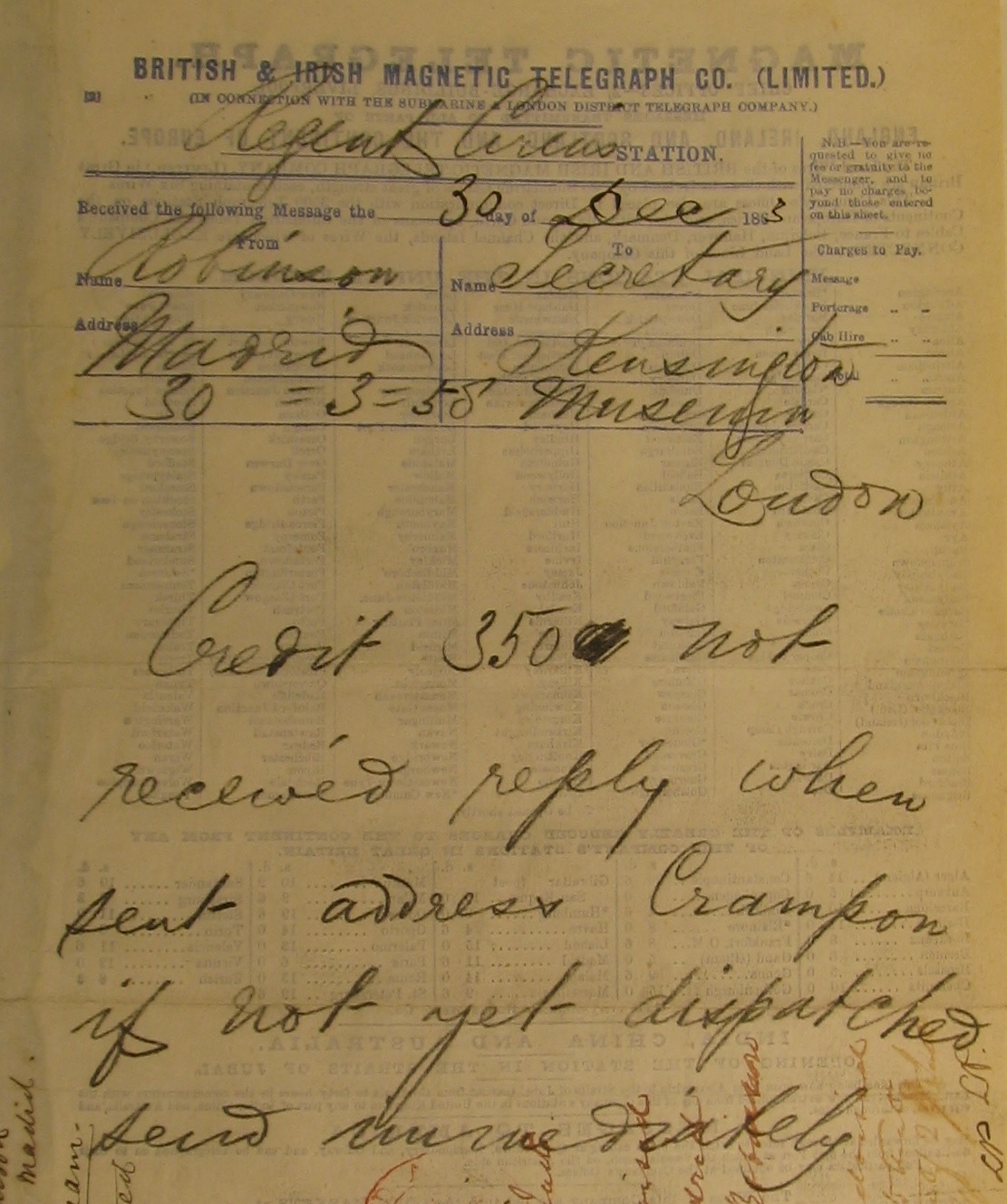

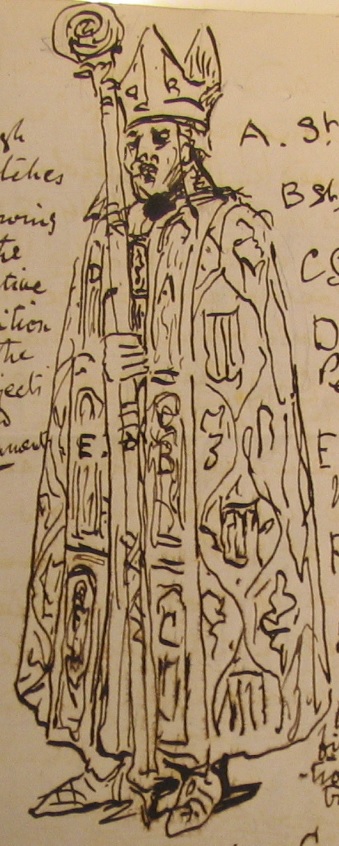

The reports are simple yet crucial testaments of this work, stating the object’s source of acquisition, its asking price, a brief description, and a recommendation of either purchase or return. They were often accompanied by sketches, letters and catalogues to be used as references for the Board.

John Charles Robinson: The enfant terrible art referee

Robinson had been the first Keeper of the Art Collection, an appointment made by Henry Cole in 1854. He was opinionated, clever and forthright, who in his reports disputed with dealers, haggled over prices and challenged authority.

One of the most famous objects in the V&A is the Great Bed of Ware, which was purchased by the Museum in 1931. In 1864, however, it came under Robinson’s consideration. In a characteristically frank report he declared it as ‘obviously not of an earlier date than James 1st, and so could never have been “the wonder of the 15th century”… Judging from the print it appears to be a coarse and mutilated specimen of its kind.’(2) Robinson preferred to collect perfection rather than objects with an anecdotal history or element of novelty.

He was also engaged in a war of words with the Spanish dealer Signor Foresi, who had claimed to print a damaging pamphlet on Robinson’s connoisseurship. Foresi had been insulted when Robinson chose another dealer over him for the purchase of a terracotta model.(3) In defence of his decision Robinson wrote fiercely: ‘Foresi is notorious for his malicious and abusive conduct towards persons who have unwittingly offended them.’(4)

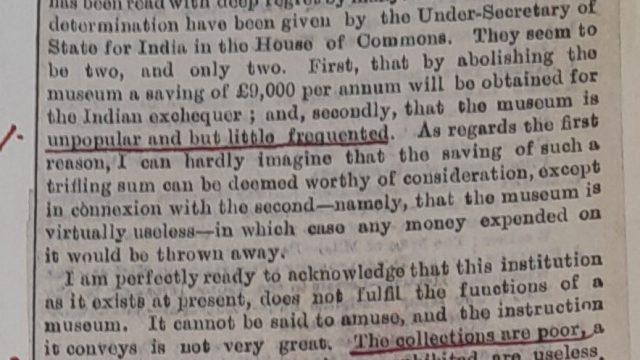

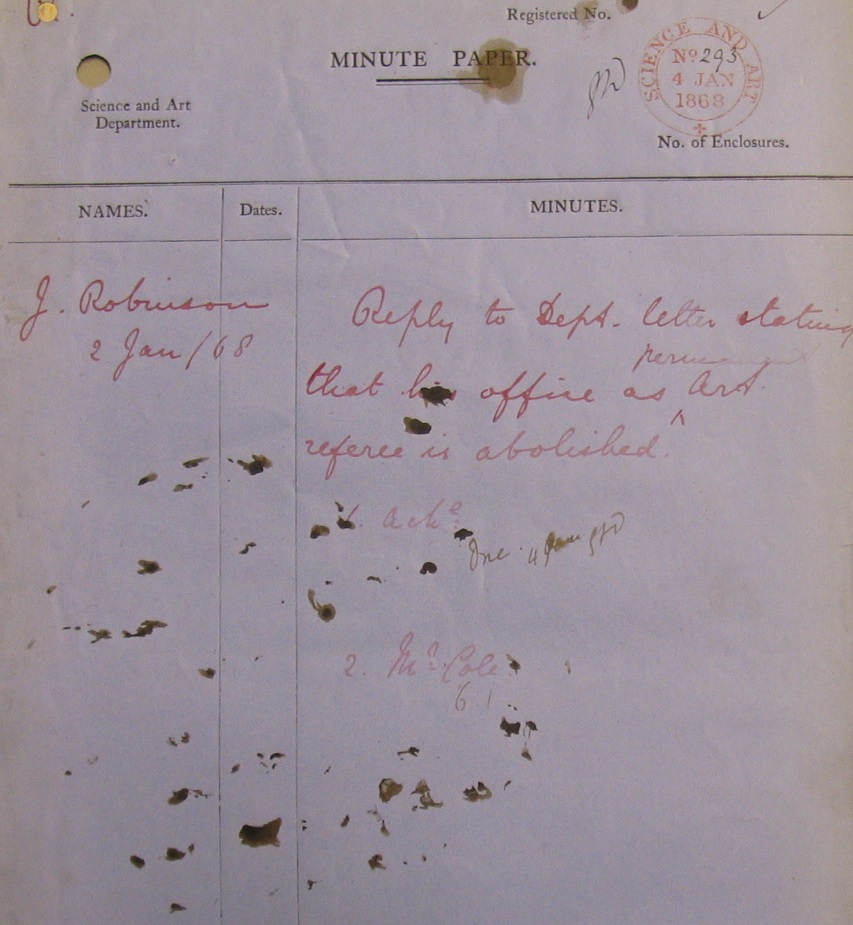

Despite acquiring outstanding pieces for the museum, Robinson did not leave the V&A under happy circumstances. He was removed from the position after the Board suspected he was buying objects to sell on at a profit to the Museum. In a furious letter to the Duke of Marlborough (Lord President of the Council), he wrote with trademark modesty: ‘I have served the country for more than twenty years, of the prime of my life for the great part of that time, in a most difficult unprecedented and responsible position, and with a success, which it is but simple justice to myself to say has attained a recognition not confined to this country alone; and yet without a word of previous warning, I am suddenly deprived of my public position’.(5)

After his employment at the South Kensington Museum was terminated, Robinson went on to become Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures.

Art referees as tastemakers

The Victoria & Albert Museum has always evolved through the tastes of its curators, being a unique institution which did not start with a founding collection (as is the case with princely collections or museums such as the National Gallery or British Museum). The art referees had a privileged chance to shape the direction of the collection. Robinson was a strong proponent of medieval objects, as well as following the museum’s taste for Italian Renaissance art. ‘Modern’ works of art were almost universally unpopular in this period. Architect Matthew Digby Wyatt decreed a 19th century Japanese bronze hibachi as ‘like almost all Japanese art – industry not without merit but in no wise[sic] beautiful, or of exceptional merit.’(6)

A referee would not, however, always have the last say. Despite Wyatt viewing and rejecting a statue of a reclining female, the Board (in an unprecedented act) requested that three other referees also inspect it. These other referees were sculptors Thomas Woolner and Richard Westmacott, and painter John Everett Millais. While the two sculptors agreed on the statue’s aesthetic value and deserved place in the Museum, Wyatt and Millais had starkly different views. Millais wrote to the Board: ‘I have no hesitation in saying that it is a very indifferent piece of work, badly modelled, & wanting all the requisites to make it a desirable acquisition to the museum.’(7) Interestingly, the Board objected to the opinions of the sculptors, and the figure was not purchased.

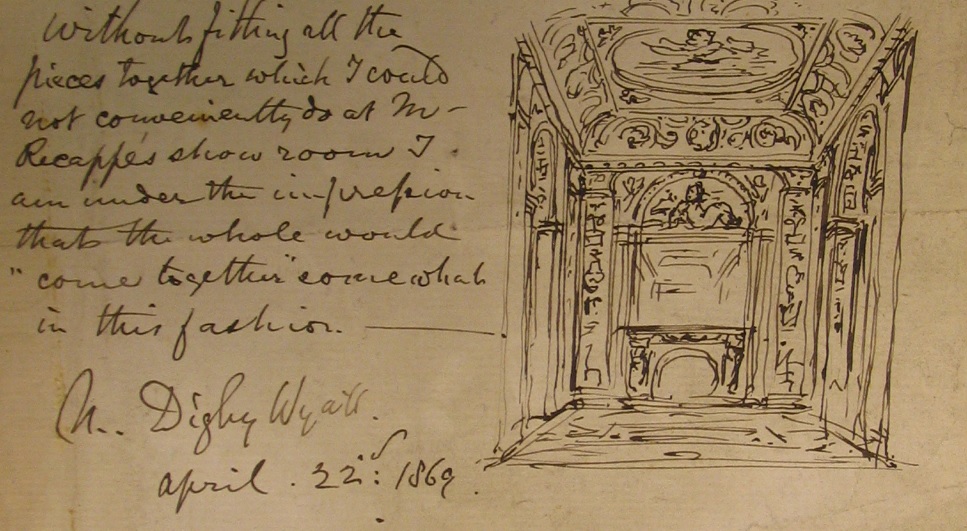

In the 1870s the museum increasingly sought out period rooms which could demonstrate stylistic contexts for museum objects. Several of these purchases failed, including plans to buy an interior of Clarendon Hotel in 1873, and the mural decorations and other interiors of the Chapel of Forio, Naples. The intention was to construct the marble chapel and ante-chapel to demonstrate ‘the luxury of the XVIIIth century’. This purchase, at a cost of £1,000 in 1870, was deemed to be too much for the Board.

A more successful campaign was the acquisition of the ‘Serilly cabinet’, purchased in 1869, which has recently been reinstalled in the new Europe 1600-1815 galleries.

The reports offer a remarkable insight into the foundation of the Museum collections and the referees themselves. While the organizational structure of the Museum has significantly altered in the past 150 or so years, the core principle of its curators has remained the same: to collect the best and the most inspiring examples of design.

Want to find out more about Art Referees at the V&A Archive? You can find a study guide here.

(1) J. C. Robinson, ‘Our Public Art Museums’, Nineteenth Century, December 1897, pp.962-3

(2) Art Referee Report from J. C. Robinson (V&A Archive ref. MA 3/9; RP/1864/14604)

(3) Jeremy Warren, ‘Forgery in Risorgimento Florence: Bastianini’s ‘Giovanni delle Bande Nere’ in the Wallace Collection’, The Burlington Magazine, Vol.147, No. 1232, Italian Art (Nov 2005) pp.729-741

(4) Art Referee Report from J. C. Robinson (V&A Archive ref: MA/3/4; RP/1863/13876)

(5) Art Referee Report from J. C. Robinson (V&A Archive ref: MA/3/25; RP/1868/293)

(6) Art Referee Report from Matthew Digby Wyatt (V&A Archive ref. MA/3/46; RP/1875/3045)

(7) Art Referee Report from John Everett Millais (V&A Archive ref. MA/3/28; RP/1869/23)