Furniture Stores and Early Decant Days . . . Written by John Williams, V&A Decant Volunteer

It’s late-January and although the V&A’s move from Blythe House to a purpose-built facility at the Olympic Park has just been publicly announced, we’ve been volunteering on the Stores Decant project for nearly three months. Drawn from a wide variety of backgrounds we were brought together as a team last November to help the Furniture, Textiles and Fashion department prepare for the move, a complex (and fascinating) project by any standards.

Our initial challenge, on which we are now making significant progress, is to audit, barcode and (where required) photograph the Furniture and Woodwork collection of circa 14,000 objects. Actually it’s more like 20,000 items to process since many of these objects have multiple, individually-numbered parts – a cabinet for example will typically have a part-number for each drawer. Once all that’s done there’s the little matter of the Textiles & Fashion collection of some 80,000 objects, but one step at a time.

So in every case we first ensure that the object is in its correct location within Blythe House (that is, according to the museum’s Collection Management System database) then we apply a barcode sticker via the paper “luggage tag” that should already be attached. In cases where there isn’t already an image on the system, then we take a photograph of the object, known as a record shot, and upload it to the database. In many cases these images will then be accessible by the public, and other museums, via Search the Collections on the V&A website.

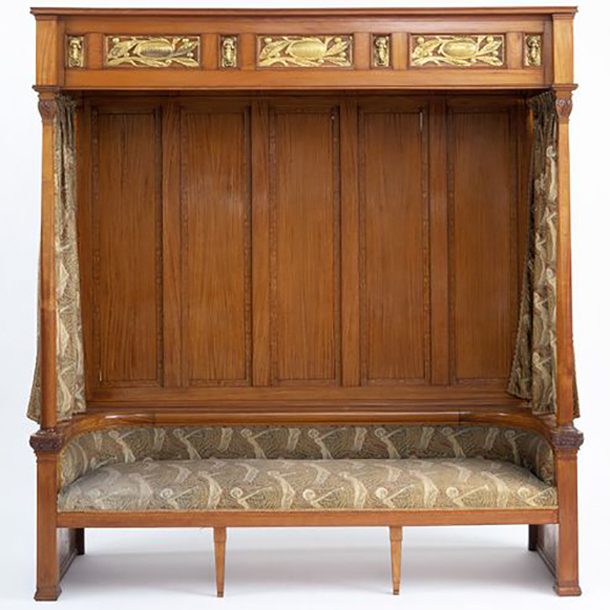

When opening-up any of the large mobile-storage racks for the first time, you never quite know what you will find. Objects (or their constituent parts) can range from small bags of fragments to pieces of such size and complexity that you wonder how they ever got into the shelving in the first place. An example of the latter is this late 19th-century settle, designed by Arthur Mackmurdo for the “beer-baron” Henry Boddington.

Even the term settle was new to me but luckily the Curator of 19th century furniture, Max Donnelly was on-site that day and kind enough to give the team an impromptu overview of this beautiful piece of furniture – not just the fascinating story of its production but also the technical challenges that would be involved in displaying such a large freestanding object, with original upholstery, in the main South Kensington museum.

Although it’s currently in storage there are already high-quality images of the settle available to the public via Search the Collections and, like all the objects at Blythe House, it can be viewed by appointment.

After a few weeks you gain a basic familiarity with the layout and general “filing system” at Blythe House. Of necessity it’s complicated, but on the whole is based on a combination of material, age, function and size. There’s always the chance however that you may be expecting a rack full of, say, 17th century woodwork but come across something completely different, as was the case when I noticed some chrome tubing peeping out from beneath a protective sheet.

This striking chair was purchased by the V&A in 1970, possibly at the Cologne Furniture Fair where it was first shown by its Milanese manufacturer, Busnelli. The letters “CIRC” in the museum number indicate that it was acquired by the museum’s Circulation Department which, from the immediate post-war period until 1976, collected and shared the best of contemporary design with regional museums, galleries and art colleges. Unlike the settle mentioned above, there isn’t currently a publicly-available image of this chair, something that we should be able to correct as part of our work.

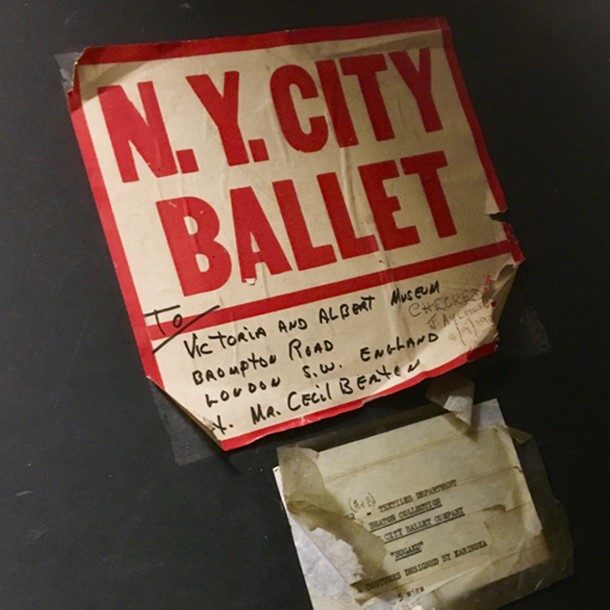

Occasionally some of the items that we find in the racks aren’t registered museum objects at all (and therefore not on the Collection Management System) but still have stories to tell, or at least to imagine. This packing box caught my eye as its external labelling didn’t seem to relate to its present contents (namely parts of a bed).

A quick piece of detective-work revealed that the box had crossed the Atlantic in 1970 containing costumes and wigs designed by Barbara Karinska for the New York City Ballet’s production of George Balanchine’s ballet “Bugaku”. And just to add further glamour, they were owned by the great photographer and costume designer Cecil Beaton, who seems to have taken personal delivery of them at the museum. We can now think about whether the box should be reunited with the costumes, which are stored elsewhere in the building.

All of the above makes for rewarding twice-weekly sessions. As well as the satisfaction of knowing that we are laying the groundwork for a huge, internationally-significant project we are also, in a small way, helping to improve the current accessibility of the museum’s reserve collections. We have even had the chance to pass on some of our early experiences to a delegation from the Houses of Parliament Restoration and Renewal Programme, who have their own challenges ahead.

But for now, back to the barcodes…