by Simon Fleury, Senior Preservation Conservator

‘Delicate things become objects late on: That is what they have in common with numerous seemingly self-evident things that only mature to the point of conspicuity once they are lost.’1

Richard Redgrave, the first curator of the South Kensington Museum (SKM) as the Victoria & Albert Museum was then known, produced groundbreaking work via his ‘condition reports’. These reports exposed strange, intimate secrets behind the creation of some of the greatest artworks within the Museum but did so by interpreting these material analyses via a utilitarian approach to conservation and institutional commerce. It is testament to Redgrave’s groundbreaking work that the conventions he employed in his painstaking cartographies are easily recognisable; many are still used today by museum conservators throughout the world. They also represent one of the earliest and most ambitious uses of the photograph, in a museum, to document the condition of works of art –a nascent experimental manifestation of the symbiotic relationship between technology and cultural practice at the V&A.

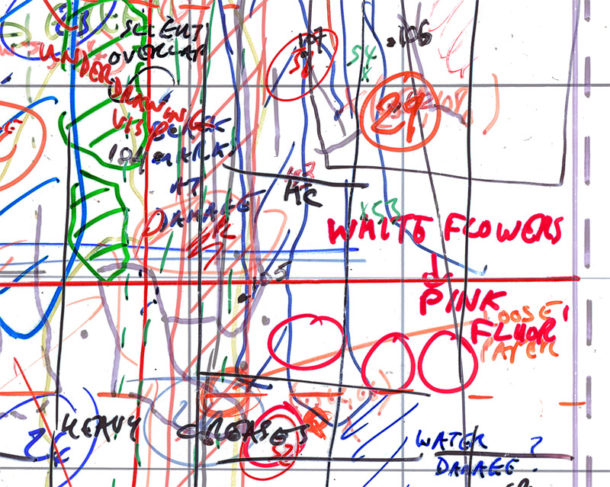

Redgrave was tasked with assessing the condition of the Raphael cartoons at the time of their move from their home at Hampton Court Palace to the South Kensington Museum. Their arrival at the SKM in 1864, on loan from HM Queen Victoria, set in motion a complicated relationship between the artwork and its corresponding documentation in the Museum. In response to these concerns for the material condition of the cartoons, Redgrave took up a pen to annotate a photograph. By inscribing directly on the photographic surface, he created a new form of material history of the object, the first photo-based condition report. In his official report on the cartoons, as the Inspector General for Art, Redgrave wrote, ‘It was necessary to take careful notes of the state of the whole on their arrival, in order that what injuries they have heretofore suffered maybe carefully noted, as well as the natural decay of age.’2

One of Redgrave’s condition reports of the cartoons (there are seven in the series) was first discovered by the author while working on the preparation of objects for a re-display of the V&A’s Photography Gallery. The albumen photograph (Museum Ref. 76.601), mounted on a secondary paper support, was in need of minor repairs – not surprising given what we know of its past utilitarian use. Over time the conventions Redgrave laid down in his reports have morphed into a sophisticated means of encoding the material condition of objects (see Battisson and Egan article in Journal 64).

Evidence of the cartoons’ past life is visible in the fine detail of the albumen print and Redgrave’s painstaking annotations. Although long past its original instrumental function, it is still possible to make out the object’s complex structure. Redgrave’s concerns for the stability of the cartoons were not only directed at the frailties of their original construction, his report also gives a sense of their past life. It is easy to forget that these rare examples of Renaissance history painting were themselves once designs, instrumental to the making of tapestries.

A research question in the making: aside from the concerns with its condition it was intriguing that this object, once essential to institutional commerce, was soon to be exhibited in a gallery dedicated to the canon of photography. As museum conservators, we are attentively attuned to the vagaries of the objects in our care. One develops a pragmatic intimate knowledge of their shifting materiality. However, this object seemed to suggest that it is not only materials that are in a state of flux at the Museum. Why was the condition and treating of an object made as a condition report of another object now being assessed? Redgrave’s once instrumental photographs had returned, reconfigured as museum objects in their own right. The images documenting recent minor repairs and interventions, which included the high resolution object image downloaded from the V&A’s digital database, had also become entangled, caught-up with Raphael’s ‘original’ design for a tapestry (cartoon).

To make sense of this contingent mechanism, the author’s practice-led PhD (AHRC/M3C, Birmingham School of Art and Design) follows the genesis of the condition report at the V&A. By concentrating on the informational material that has crystallised around the Raphael cartoons while at the Museum, it traces a lineage of practice that runs from Redgrave’s early work through to the latest, and no less innovative, digital iterations (Figure 1). By fabricating new hybrid museum objects this experimental research aims to counter the normative ‘neutral’ understanding of conservation and techno-cultural production, and by so doing, make a significant contribution to the fields of contemporary art and museum research.

References

- Sloterdijk, Peter. Foams: Spheres volume III: Foams Plural Spherology. South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext, 2016, p.61.

- Richard Redgrave, Inspector General for Art, 1857-88. Report on the State of the Raffaelle Cartoons, Report of the Commission on the Heating, Lighting and Ventilation of the South Kensington Museum. London: HMSO. Appendix C (3), p.7.