As the Chelsea Flower Show draws to a conclusion tomorrow, and the masses return to their own gardens inspired, it’s worth looking back to the 18th century, to the golden age of botanical exploration and to an artist who was arguably the finest botanical painter in history – Ferdinand Bauer – and how expertise at the V&A is helping to understand how he worked in the field.

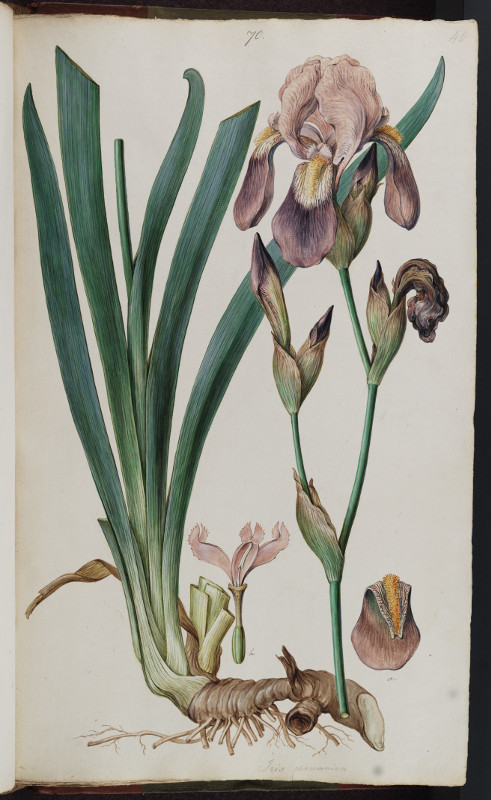

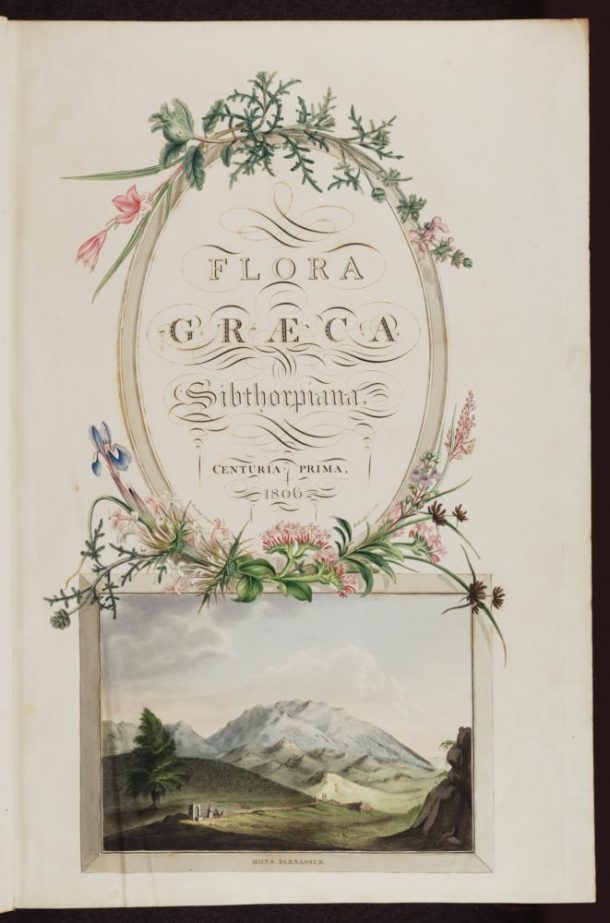

Outside of the natural sciences, Bauer (1760-1826), is little known. Along with his equally talented brother Franz however, he is certainly known to botanists. He has been called ‘the Leonardo of botanical illustration’, and is known in particular for the beauty and accuracy of his illustrations of flowers. Nowhere is this seen more clearly than in the paintings he made for the exquisite Flora Graeca, one of the most expensve publications of the 18th century, and certainly one of the greatest botanical works ever produced. Unprecedented in the quality of its illustrations, its printing and its attention to naturalistic detail, the Flora Graeca described the flowers of Greece and the Levant, and was published in ten lavishly-printed volumes between 1806 and 1840 to an elite group of only 25 subscribers. It was the legacy of the third Professor of Botany at Oxford University, John Sibthorp (1758-1796). Sibthorp met Bauer in Vienna in 1786, and immediately engaged him to join his expedition to collect and record specimens, and ultimately to paint the almost 1500 watercolours of plants and animals he sketched on his return to Oxford in 1787.

What is of interest to us however is that Bauer used a particularly unusual technique to record his specimens in the field…

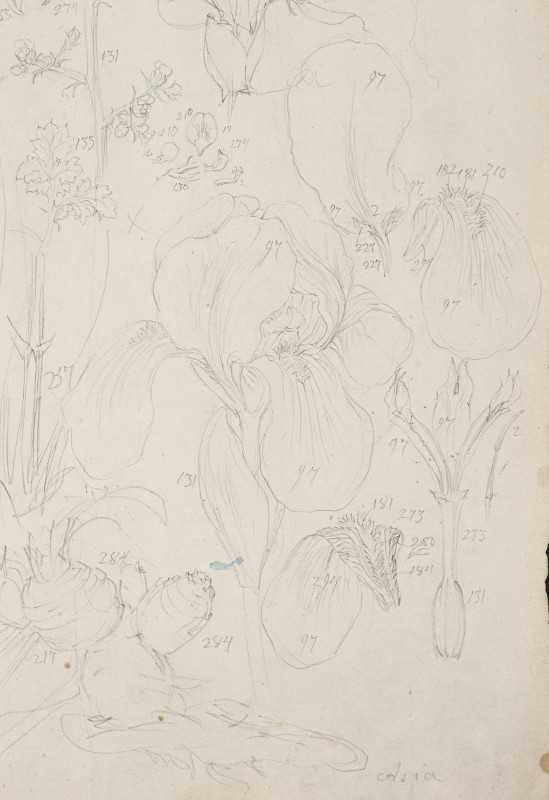

Bauer is exceptional among travelling botanical artists for the unusual techniques he employed for recording colour. He certainly observed and sketched live specimens, but he did not annotate these sketches with colour in the field as other artists did. Rather, subject to the limitations of working in the field – moving from place to place quickly in often difficult territory, and unable to carry large amounts of painting materials with him, he collected and dried specimens, making only very basic pencil sketches on paper. He recorded the vital colour information, lost almost immediately after a specimen was picked by annotating these drawings with a series of numerical colour codes (below) which likely referred directly to a painted colour chart, now lost. That Bauer’s 1500 paintings were created within a period of 6 years using only this colour reference system, and sometimes up to five years after seeing the original plants, and that they are highly regarded even today for their botanical accuracy, speaks to his expertise as an artist and his astonishing memory for colour.

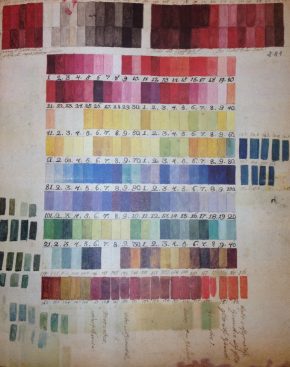

Ferdinand Bauer (and to a lesser extent his brother Franz) appear to be the only significant natural history artists to have used this kind of colour code in a practical way. Numerical codes of up to 140 different colour tones are found on early drawings by both Bauers from the 1770s. However, where Ferdinand seems to have continued to develop this initial system of some 140 colours into one of at least 273 colours for the Flora Graeca (and from then into a considerably more complex system of 1000 colours for a later expedition to Australia in 1801-5 – though how he could have used this practically is anybody’s guess), Franz Bauer, who was by then official botanical painter to Joseph Banks at the Botanical gardens at Kew, did not did not appear to use the system after he came to London in the late 1780s. Ferdinand of course, spent a significant amount of his time working in the field, and therefore much more in need of a system of shorthand than his brother. However, it’s interesting to note that no other travelling botanical artist used such a system to the extent that Bauer did.

An early colour chart (below) that appears likely to have been used by the brothers was found in 1999 at the Madrid Botanical Gardens, but Ferdinand Bauer’s 273 colour chart related to the Sibthorp expedition and the 999 colour chart he may have used for the Matthew Flinders expedition to Australia, if they ever existed, have never been discovered.

This fact, however, presents a unique opportunity for us to carry out technical research into Bauer’s materials. The Conservation Science section at the V&A are collaborating with Oxford University, Durham University and the University of Northumbria on a large research project at the Bodleian Library, Oxford University that will help to understand what the Flora Graeca colour chart may have looked like, and how Bauer might have used it. Funded by the Leverhulme Trust, the Bodleian project aims to identify the pigments used by Bauer in his magnificent Flora Graeca watercolours, cross reference these results with the numerical codes in his field sketches, and ultimately create a historically-accurate reconstruction of the lost colour chart.

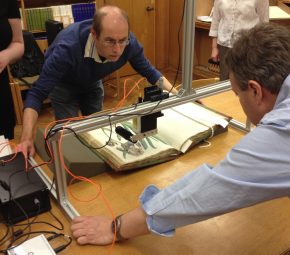

How will we do this? Often it is permitted to remove a minute sample of paint from a work of art in order to identify the material components. However this is rarely possible with watercolours, and is most certainly not possible for one of the treasures of the Bodleian’s collection. The work therefore is carried out in situ, bringing portable instruments to the object itself, rather than the other way around. For this we currently use three analytical techniques at Oxford: Raman spectroscopy, X-ray Fluoresce spectroscopy (XRF) and Hyperspectral imaging (Imaging spectroscopy).

The V&A Conservation department has a long history of collaborating with universities on technical research, and since the Conservation Science section has a great deal of expertise in Raman spectroscopy and its use in identifying pigments on artists’ watercolours, it is ideal that the V&A can lend this expertise to Oxford and collaborate with our academic partners.

I think that this project showcases the value of technical art history, a field that has long been associated with the V&A. It will go some way toward an understanding of Bauer’s extraordinary feel for colour and pigment, how he utilised his colour code, and ultimately how he was able to achieve such an impressive degree of colour fidelity in his work.

As we progress with the project, and as we learn more about Bauer’s materials and techniques, I’ll post again with more results and revelations. But should you find yourself in Oxford before September, several of Bauer’s paintings are on display in the Marks of Genius exhibition at Bodleian’s Weston Library – the old “New” Bodleian – which has opened to the public for the first time in 400 years (!) after an £80 million refurbishment.

More importantly however, you’ll also find a number of other V&A connections there, from the Bodleian Reader’s chairs, designed by competition, and displayed in the V&A’s Furniture galleries in 2013 and, more impressively, the huge and fully restored 16th century Sheldon tapestry map of Worcestershire, part of the Bodleian collection and held by the V&A for many years, a companion to the museum’s own Sheldon tapestry collection . I highly recommend it.