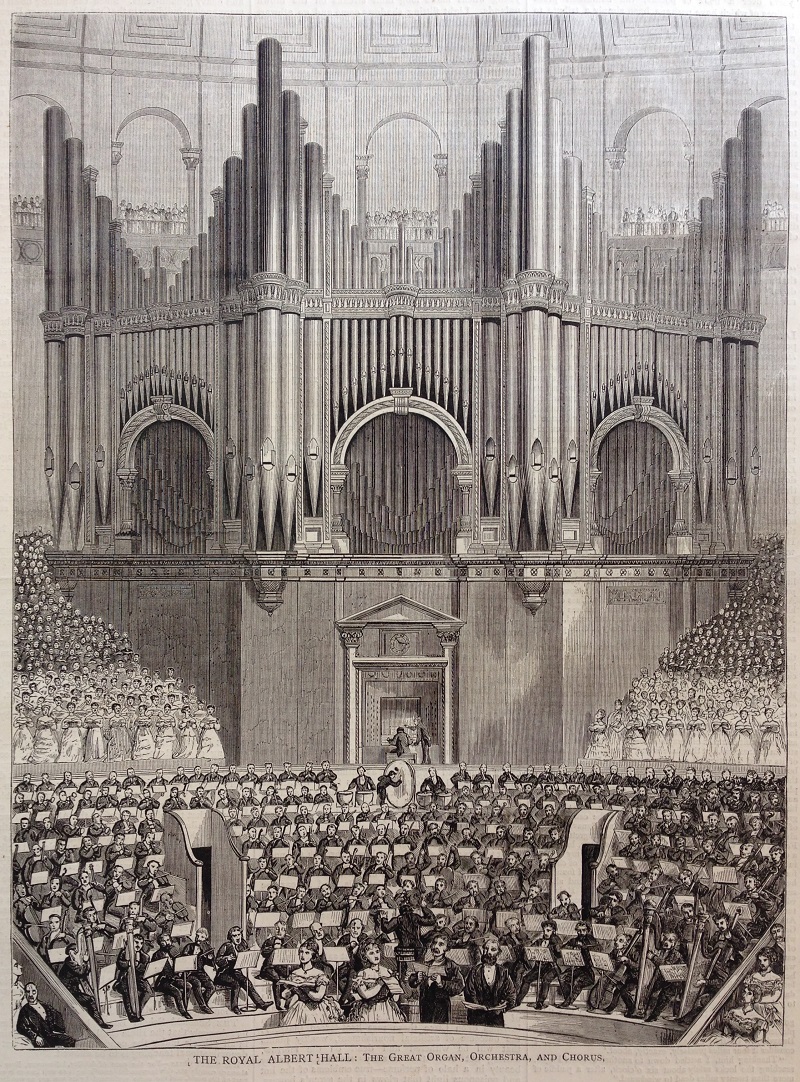

The BBC Proms season is only just underway so it seems somewhat premature to mention the climactic Last Night of the Proms, when the bronze bust of Sir Henry Wood, borrowed for the duration of the concert series from the Royal Academy of Music and set on a plinth immediately before the Royal Albert Hall’s Grand Organ, is ritually adorned with a laurel wreath.

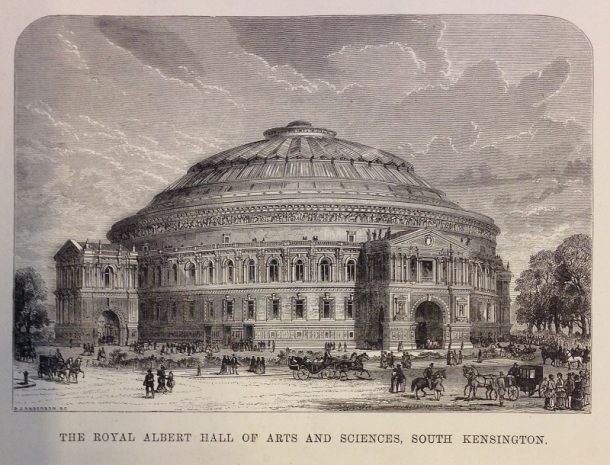

I reckon, however, that another Sir Henry – Sir Henry Cole (1808-82), the V&A’s first Director – has fair claim to a laurel wreath of his own for his Herculean efforts to realise Prince Albert’s vision of ‘a central institution in London for the promotion of scientific and artistic knowledge as applicable to productive industry’ (Illustrated Newspaper (18 May 1867)), of which the erection of the Royal Albert Hall was a key component. In fact, such was the extent of Cole’s involvement (he sat on the project’s Executive Committee) that someone quipped in Vanity Fair that ‘It was first christened the “Central Hall of Arts and Sciences,” but Art and Science having given way to harmony, it is now proposed to call it “The Central Cole Hole” (8 April 1871). Cole’s contribution has been recognised to some extent at the Royal Albert Hall where there is a Henry Cole Room, which fittingly ‘features art that depicts the history and construction of the Hall’.

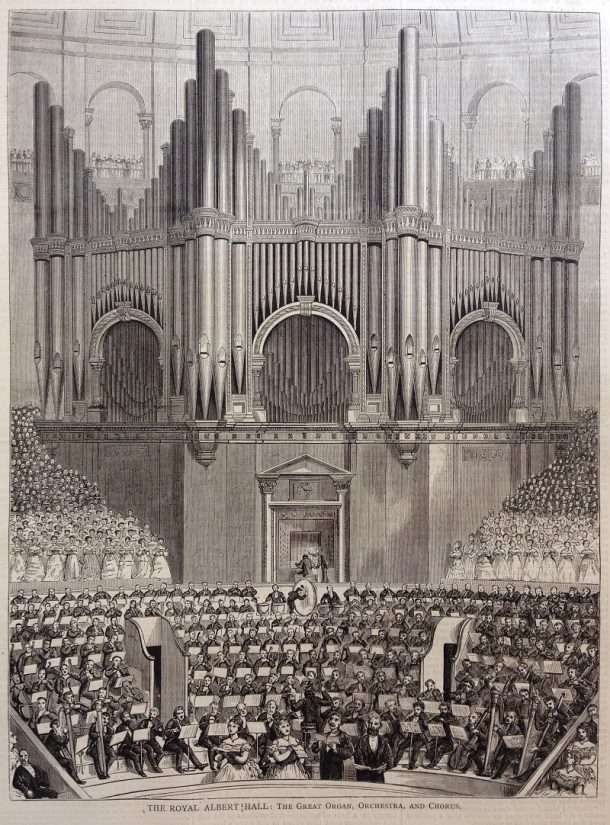

In this blog I thought I’d use Cole’s diary and an album of press cuttings, 1865-76, which relate exclusively to the Royal Albert Hall (V&A Archive, MA/49/1/50), to cast some light on the Grand Organ that dominates the Hall’s magnificent interior.

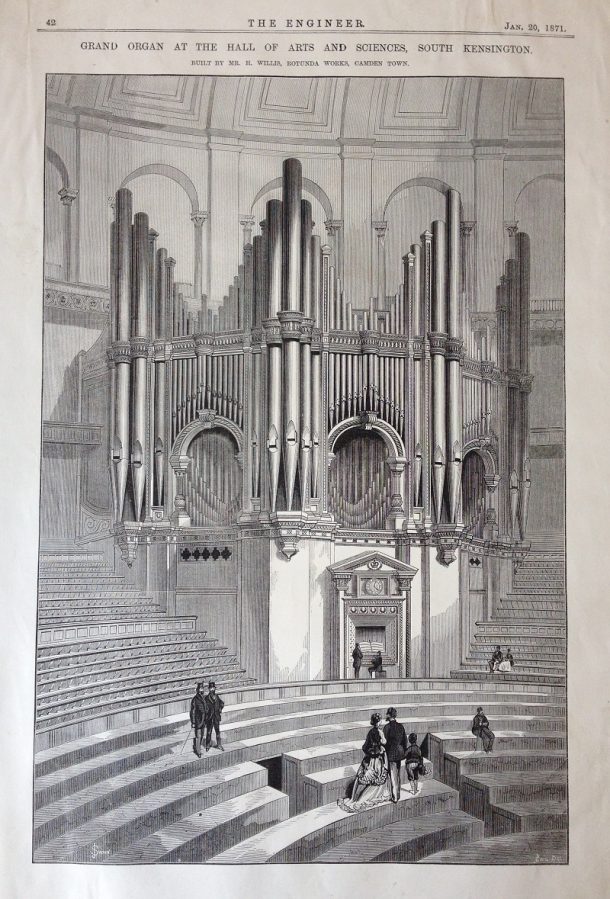

In 1870, Henry Willis (1821-1901) of the Rotunda Works, Camden Town, the foremost organ builder of the nineteenth century, was commissioned to design, build and install the Royal Albert Hall’s organ. Its construction was subject to the approval of an advisory committee, which comprised professional and amateur musicians: the Earl of Wilton, Lord Gerald Fitzgerald, the Hon. Seymour Egerton, Professor Tyndall, Sir Michael Costa, Mr. Bowley, and Mr. Stephenson.

Specialist publications took a keen interest in the organ’s specifications and mechanism. The English Mechanic (8 April 1871) in particular sought to dazzle its readers with an inventory of the organ’s impressive vital statistics: it was 65 ft. wide, 70 ft. high and 40ft. deep; weighed over 150 tonnes; comprised nearly 10,000 pipes, the largest of which were 2 ft. 6in in diameter, the smallest ‘not much thicker than a barley straw’; if placed end to end the pipes would stretch 9 miles; there were no less than 138 stops, 20 couplings, and 60 combination pedals and pistons; the keys, made of ivory, were so finely balanced that ‘the least touch is sufficient to sound them … any lady could play upon it with the same ease and with the same rapidity as she could on a cottage piano’.

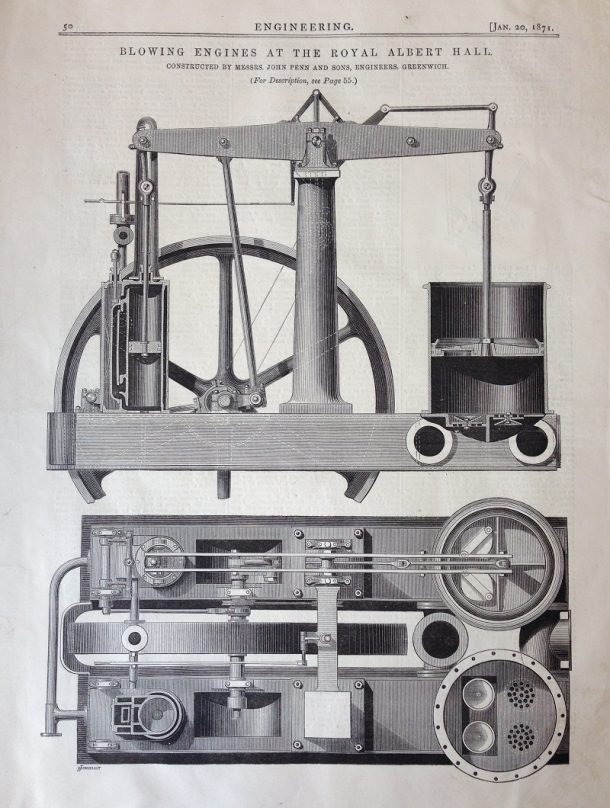

In addition to its gargantuan size – when completed it was the largest organ in the world – a key innovation was the construction by Messrs. John Penn and Son, Greenwich, of a pair of blowing engines to feed air into the six pairs of bellows or ‘feeders’ at a higher pressure: the English Mechanic observed approvingly that the engines would ‘be able to work up to 50-horse power with ease and give the very decided pressure of air required for playing with full power when all the stops are opened’.

Although not a member of the organ advisory committee, Cole’s diary reveals that he took a close interest in the organ building project, which would cost a cool £10,000. The following extracts relate to the process of building and fitting the instrument. While Cole’s entries are more concise than we might wish, his observations nonetheless give us tantalising glimpses into the instrument’s construction timetable, the contractual negotiations with the Hall’s resident organist, flaring artistic temperaments and the frantic preparations to get the interior of the building finished in time for the official opening by Queen Victoria. The individuals to whom Cole refers are: Sir Michael Costa (1808-84), conductor and composer: in 1865, Cole had heard his oratorio ‘Naaman’ and judged it ‘very rich & full in Harmony & Instrumentation. Perhaps wanting contrast’ (12 May 1865); Henry Willis, organ builder; Robert Bowley (1813-70), musician and general manager of the Crystal Palace; William Thomas Best (1826-97), organist and composer; Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900), composer and one half of Gilbert and Sullivan; and Seymour Egerton (1839-98), musician and associate of Arthur Sullivan, whose Guarneri violin was later owed by Yehudi Menuhin.

11 January 1870: ‘with Costa to see progress of Great Organ by Willis. examined movements & pipe casting’

15 March 1870: ‘Costa Bowley & Willis called to settle where organ pipes cd be put’

23 March 1870: ‘To Willis’ Works to hear the first seven stops first tried. tone brilliant’

6 December 1870: ‘Mr Best of Liverpool called, wd come to London for £500 a year for 2 performances a week’

7 December 1870: Mr Best went to Hall. wanted a 5 year guarantee’

13 December 1870: ‘Costa & Sullivan approved of Bests Terms for organ of Hall’

5 January 1871: ‘Organ shed removing. Willis objecting, having said it was in his way’

27 March 1871: ‘Willis behind with his pipes’

28 March 1871: ‘To Hall. Candles burning every where. Carpenters at work on benches. Organ front unfinished’

29 March 1871: Hall before 8 … Organ in litter: Chandeliers in paper. Bare boarded. left so. R. A. Hall opening with Success’

26 April 1871: ‘Mr Best came to see Organ & decided not to use it till it was complete’

5 July 1871: ‘Costa said he wd not examine instrument till Willis wrote to say it was ready’

14 July 1871: In the Evg … to Bests examination of Organ before Costa and Seymour Egerton’

23 July 1871: ‘The first Sunday Organ performance in the Hall’

24 July 1871: ‘Costa with Scott about the organs incompleteness’

After all his exertions, it seems ironic that Cole did not attend the inaugural performance given by William Best on 18 July 1871, attending instead a performance of Domenico Cimarosa’s comic opera Le astuzie femminili (1794; London premiere 1804) at Covent Garden. A review in the Musical Times (1 August 1871) gave an account of the repertoire that Best performed and the reaction of the audience (1073 concert tickets to the event were sold):

“It is unnecessary to say that Mr. Best’s rendering of the pieces selected was in the highest degree satisfactory; and, although in the Prelude and Fugue of Bach in E flat, (St. Ann’s) we scarcely agreed with the occasional alteration of tempo, our opinion appeared in no degree shared by the audience; Handel’s Organ Concerto (No. 1) and Mendelssohn’s Sonata (No. 1) were finely played, the Adagio in the latter narrowly escaping an encore. A Choral Song and Fugue, on a theme by Travers, by Dr. S. S. Wesley, an Andante Grazioso, by Mr. Hopkins, and an air with variations by Mr. H. Smart (the two last named being performed for the first time) were excellent specimens of recent works especially for the instrument and all of them were received with marked favour.”

Best also performed two compositions of his own: a March in A minor and ‘Andante pastorale’ and fugue in E major. The audience was on its best behaviour: ‘Mr. Best’s performance was listened to with earnest attention, and the applause at the conclusion of each piece was spontaneous and enthusiastic’.

Although the organ has been rebuilt twice since Willis installed it, Prommers will have an opportunity to hear it put through its paces when Thierry Escaich gives an all Bach recital on 23 August 2015.