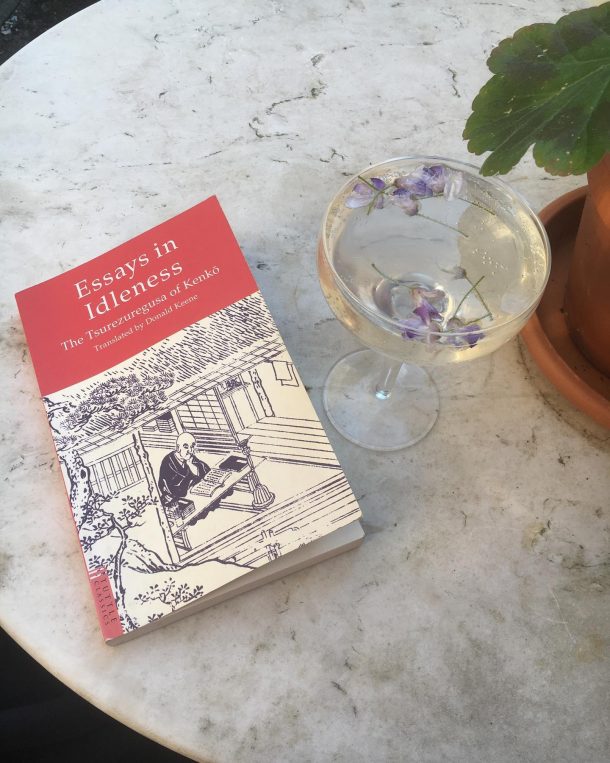

The cocktail glass, and the associated ‘quarantini’, was an aspirational approach to lockdown, an embrace of leisure and online posturing, naïve of what was to come and now already tinged with nostalgia. While cocktail glasses are certainly not the most democratic object, they are the kind of object one has but never uses. I don’t have much superfluous kitchenware, certainly no fine china or silver flatware, but I do have a set of martini glasses that were purchased from a charity shop with the romantic notion that by having them I would transform into a modern-day Dorothy Parker, or at the very least Miranda Hobbes. But like high heels they have spent most of their time with me as unused material reminders that my life simply isn’t that glamorous. Lockdown may have been the death knell for uncomfortable fashion, but we finally had time to make some seriously strong drinks for the gram #quarantini.

While cocktails have been around since the 19th century, it was Prohibition America that popularised the martini, while the history of its associated glass, defined by its conical shape and slender stem, has lore of its own. The martini glass was first exhibited in 1925 at the Paris International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts. Embodying the aesthetics of Art Deco with its angular form, the glass was an update on the champagne coupe. Since being appropriated for the martini, the design is often praised for its functionality, the stem ensuring hands don’t warm the icy contents of the bowl and wide brim thought to complement the concoction. However, it’s also very easy to spill, making it an ideal speakeasy glass in case the contents need to be emptied quickly.

(CIRC.34-1970), Presented by Arthur Byron. ‘Empire’ Cocktail shaker, designed by William Archibald Weldon made by the Revere Brass and Copper Company, Rome/New York, 1938, (M.227-1984)

I first tried a martini while living in Japan, where the art of cocktail making has been mastered to such a high level that in 2008 Bon Appetit magazine proclaimed Tokyo the ‘cocktail capital of the world’. Indeed, the making of these drinks is taken seriously, with specially selected ingredients, careful preparation, beautiful presentation and ensuring the environment is just as pleasurable as the concoction. Although considered quintessentially American, cocktails have a long history in Japan and were first served at the Yokohama International Hotel bar in 1874. Many attribute the quality of Japanese bartending to its preservation of golden age cocktail culture and due to this, I had never realised just how easy it is to make a martini at home: two parts gin, one part vermouth, stirred through ice and served with an olive.

Cocktails conjure up various periods in history, including the Jazz age, 1970s disco or Y2K futurism, cultural moments of such hedonism that they could only foreshadow recession. As Richard Godwin writes in The Guardian, ‘cocktails have an affinity with strange, uncertain times; celebration and consolation in one hit’. The opulence was reinforced by celebrities drinking cocktails on social media, such as Meryl Streep’s Zoom performance or Stanley Tucci’s negroni tutorial, bolstering the comfortable lie that we were all in this together.

But as Covid-19 related deaths rose, class divisions deepened and the brutal murder of George Floyd brought global attention to the horrors of systematic racism, the desire to numb oneself to these awful realities started to seem self-indulgent. Rather, there was a sense that we should remain clear and conscious to what was happening. The Black Lives Matter protests have been marked by sobriety, with organisers asking participants not to drink. In sharp contrast, the racist UK ‘counter-protestors’ were getting plastered, with one drunkenly urinating on the very monuments they professed to be protecting. In light of these events, to sit back and drink a cocktail felt like being a sedated suburban housewife, oblivious to the outside world.

With the easing of lockdown and warm weather, public displays of drinking have inevitably reappeared in Britain, but now in the form of gin tins in the park, tentative trips to the pub, or brazen displays of travel to the continent. Will we ever return to making our own cocktails, or will those glasses be relegated to the back of the cupboard again, waiting for the next life-altering event?

Further reading

‘Happy hour: the great cocktail comeback’ Richard Godwin, The Guardian, 12 July 2020

‘Good libations: Examining the evolution of Japan’s rich cocktail culture’, Matt Alt, Japan Times, 24 March 2018

‘Why the martini glass is a classic, despite its shape: The surprising endurance of a Jazz Age design’ Jason Palmer, The Economist, 10 October 2018

‘The Life and Death of the Martini Glass’ Lizzie Munro, Punch, 17 August 2016