This post is part of a strand of research on the project Content/Data/Object. The project explores how museum practices can broaden access to digital works, so that their digital design processes can be enjoyed well into the future.

In my role as communities research fellow here at the V&A, I have been researching digital objects on the research project Content/Data/Object. Over the next year I will be writing an on-going journal for my work here on the blog. I plan to work work in an interdisciplinary way with others – including activists, makers and members of the public. An important element of this collaborative approach is inviting you into my research process too, to share some of the interesting and challenging discussions along the way.

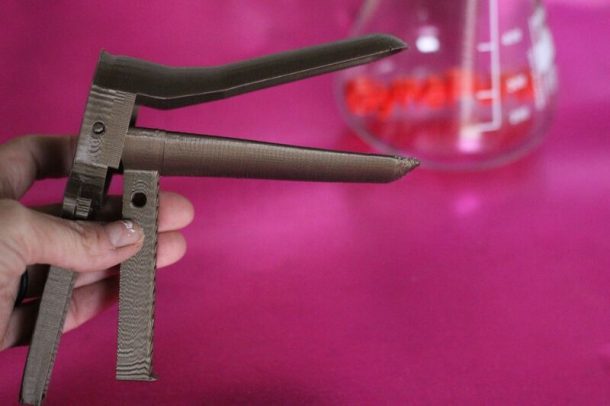

Above are two images of two different 3D-printed objects. One is a firearm, a potentially deadly weapon – the other a speculum, a gynaecological instrument. Both objects are contemporary, made of plastic and opensource. This means that their designs are distributed online, freely available to anyone with internet access; so that they can be readily made by others. Both objects share a radical ambition – they have been designed as disruptive, political acts.

Depending on an individual’s beliefs and political convictions, both the opensource gun and the opensource speculum embody an idea of freedom through design. This process of online circulation provides access to objects or practices that are restricted to certain systems and people in societies. It’s through these opensource versions that restrictions are pulled apart and questioned. Therefore the gun and the speculum might be deemed as dangerous and unsafe – unregulated. Or, by contrast, they could be viewed as freeing and empowering.

We’re often led to believe that the gun is used to harm, and the speculum used to help. Although the gun by its very definition is a weapon, the latter, in its different iterations, has a violent history. A speculum is a gynaecological tool used commonly by medical practitioners to open the walls of the vagina, to check for any problems with the cervix and other reproductive organs. While this may not sound particularly threatening, specula continue to be weaponised as a form of state violence, asserting control over bodies (the link has graphic content).

The opensource speculum is a response to this. It signals the right to make decisions over an individual’s own body – bodily autonomy – while the opensource gun illustrates the US Constitution’s Second Amendment – the right to bear arms. Even placing these opposing designs together in the same paragraph feels jarring and odd. Even a bit distasteful. For me, this is because of the different political ideologies that lie behind the real felt need and desires of the people behind these political tools. Libertarian politics and contemporary feminism don’t fit so easily together.

I began my research by looking into the collection of the curatorial department of ‘Design, Architecture and Digital’ – where I am mainly based at the V&A. This led me to the gun, also known as The Liberator, which was collected by the museum in 2014. While the world’s first 3D-printed handgun has been written about countless times, it was essential to start with the V&A collection itself before exploring other models and objects.

Although sinister, The Liberator was collected as a significant piece of digitally produced design. It sparked fear and concern around the impact of opensource design. Discussions with my project leads and V&A curators, Corinna Gardner and Natalie Kane, led me to think about The Liberator as a certain kind of making. A making that is informed by a need for something.

This need is part of a wider political desire, a desire where new political possibilities can be brought about, or at least, imagined through design – as opposed to purely artistic or expressive forms of making. The gun was regarded as a need, even a constitutional right, in America. The V&A object illustrates a desire for a new way of living, where access to guns is bound only by access to 3D-printers, basic skills and the internet.

However, in November 2019 the United States Supreme Court passed a new law prohibiting the sharing of a printable gun file, introducing legislation at state level, and in my own opinion, thankfully stalling the attempt of a mass, mainstream, Libertarian political future at this time.

The 3D-printed speculum, also known as the GynePunk 3D-printed speculum, represents an opposing form of freedom through design. As the name alludes, the GynePunk 3D-printed speculum is associated with the work of the feminist activist group, GynePunk. At the time of the speculum’s release, Klau Kinky (also known as Klau Chinche) and Paula Pin were the main activists and makers of GynePunk, living and working between Spain, Germany and Mexico. The GynePunk version of the speculum symbolises the subversive practices used by the feminist activists. The power dynamic played out when the modern speculum is used in common medical environments is subverted by GynePunk, through how it is used for self-examinations, and by whom.

GynePunk interrogates forms of discrimination that women, trans and non-binary people face when accessing gynaecological medical care. One way in which they do this is by creating safe spaces to practice and share the skills and knowledge of basic gynaecological healthcare, both online and in physical spaces. Much of their work focuses on the early diagnosis of cervical cancer. A speculum is commonly used to perform smear tests to help diagnose abnormal changes to cells, and prevent the development of cancer.

The rest of my time at the V&A will mostly be spent investigating the design of the GynePunk 3D-printed speculum alongside activists and other makers. It will act as my main object case study over the next year, but in future posts, I’ll expand on both The Liberator and the GynePunk speculum, continuing to pose questions around their creation as a form of need and desire.

With the speculum, I aim to examine how historic ideologies, uses and materials are embedded in the design of the object, and how through GynePunk’s use of digital materials and spaces (code and online sharing platforms), they subvert and disrupt our common understanding of the medical instrument.

Although digital tools are radically expanding access to knowledge, ideas and design, we need to continue to actively scrutinise the possible interpretations of these technologies and the intentions of those using them, before jumping to judgements about the tools themselves. Objects alone cannot bring about transformational change. Nor can ‘open’ systems of sharing, which are embedded in other systems of privilege, ideology and governance. It is people that create change.

Exploring design through human aspiration, through need and through desire, I aim to investigate how this informs finished objects, but also how the museum can appropriately collect the design processes around the creation of objects as political acts. I may only begin to scratch the surface of such huge and complex concerns. But in working with others, I’ll be in a stronger position to explore the speculum’s violent past, through probing its current radical digital existence, and its possible radical future.