Anna Kallen Talley, design historian and researcher. Currently working on a PhD at the University of Edinburgh, funded by the Scottish Graduate School of Arts and Humanities.

I’ve just spent the last three months as a placement in the V&A’s Design and Digital section working on a research project that looks at the history of collecting digital objects at the V&A and thinking about news ways the museum can go about collecting digital objects to ensure their preservation for the future (Go here learn more about what I mean by digital objects) .

I’ve long been interested in the way things are collected by museums. Some of the first work I ever did in museums was in 2018 when I worked on acquisitions paperwork for design objects at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This got me interested in how a museum decides something is worthy to save indefinitely and the process by which an object actually comes into the museum. Of course, this was all for physical objects.

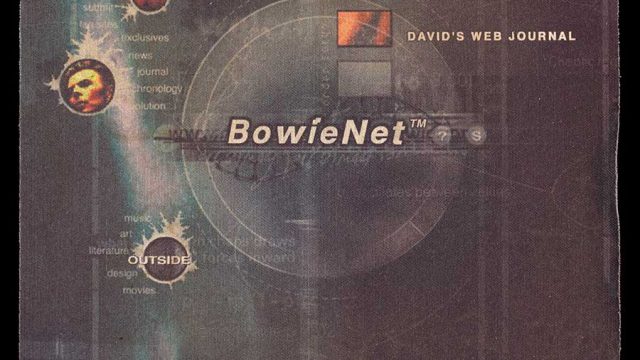

In 2020, the pandemic forced a massive shift from physical to digital life, and I began to take an interest in digital material culture. So much of our online life, just as the physical world, is shaped by design. My interest in digital objects inspired my PhD project, which looks at the history of news design from physical newspapers in the 19th century to online news websites. While conducting my PhD research, I have also thought a lot about the problem of digital being so ephemeral. I began to wonder, how could institutions like museums and libraries collect and save digital objects?

As it turns out, museums like the V&A shared this concern and were already asking the same questions. Working with the museum’s Design and Digital section, we were able to put together a research project that explored this issue of ephemerality and how the museum could improve its acquisitions process for the collection of digital objects. (Head here for more information about how a museum usually acquires objects).

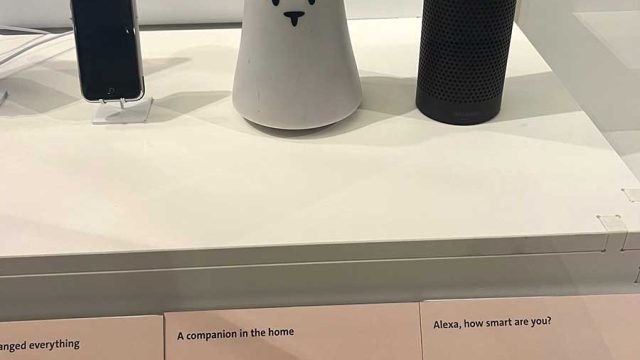

The first thing I did when I arrived at the V&A was research its history of collecting digital objects. This research was essential to help me understand how past collecting practices inform current and future ones. I began to understand what makes the collection of digital objects so complicated, for example, the fact that digital acquisitions often have multiple parts. An acquisition like Euki, a reproductive health app, might include the source code for the app, video documentation of how the app is used, the purchase of a phone specifically for Euki and other documentation from the creators. And that’s just for one object! After speaking with curators, conservators, staff in collections management and archives, it became clear that everyone had similar concerns about the complexity of digital objects. They all have the same goal, to care for objects, but I kept hearing over and over how hard that was when, with digital, ‘every object is different’.

The approach was to create a collecting digital “how-to guide” and questionnaire that could serve as a baseline for everyone in the museum working with digital objects. The how-to guide includes useful resources and contacts within the museum and helps to define how different parts of digital objects can be catalogued. It also contains suggestions for the kinds of documentation, such as images and video demonstrations, a curator might need to collect from an artist or designer to ensure the object can be understood in the future, even if the digital object can no longer function. The questionnaire is organised by four main questions that are essential to consider when collecting digital objects:

- What is it?

- How do we understand it?

- How do we keep it?

- How do we display it?

Through answering these questions, curators, conservators, audio/visual staff, collections management and makers should be on the same page about what the museum is collecting, how it’s going to be preserved and how it can be shown to the public. Now, the guide and questionnaire need to be put into practice to see how well they work. Although both will likely need to be altered once they start being used, this makes sense, especially given the ever-shifting nature of digital objects!

Throughout my time at the V&A, I’ve learnt a lot about how to work across teams in the museum and the collaborative process by which objects are collected. I’ve had the chance to hear from staff who have a vested interest in collecting and caring for digital objects, which in turn has helped me think more dynamically and deeply about how digital objects can be preserved in the future. Although now I have to go back and finish up my PhD, this short project was immensely refreshing, as it was a very different research process from working on my thesis. Usually, I’m tucked away at a desk by myself in the corner of the British Library. At the V&A, I got to work collaboratively in a team and talk to lots of different people across the museum who were essential in informing the final output. I realised that, although I’ve spent much of my academic career figuring out how to work with inanimate objects, I need to be just as adept at working with people! As a PhD student, I also have the tendency to get caught up in theory and history. At the museum, I had to translate my research into a practical output, the questionnaire, that could actually be used by the museum. In my work I’ve always foregrounded the importance of research having a real-life impact, but doing this is more difficult than it sounds!

I look forward to keeping up with the V&A team about how they’re using the guide and questionnaire and taking what I’ve learnt about the care and keeping of digital objects forward into future projects.

This placement was made possible by the Scottish Graduate School of Arts and Humanities/Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Anna Kallen Talley is a design historian and researcher. Her research focuses on modern and contemporary material culture, particularly product, digital and communication design. She is currently undertaking her doctoral research at the University of Edinburgh. Anna holds an MA from the V&A/Royal College of Art in Design History and Material Culture and has experience working with cultural heritage institutions in the US and UK.