As part of my research into religious objects for V&A East Storehouse, which will open in 2025 in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, I have been investigating religious objects in the collection from around the world.

For this post, I teamed up with Ekta Sunil Raheja, Assistant Curator in the South and South-East Asia section, to research two bronze figures of the Hindu deity, Hanuman, exploring his history in literature and how the sculptures made their way into the V&A collections.

History and worship

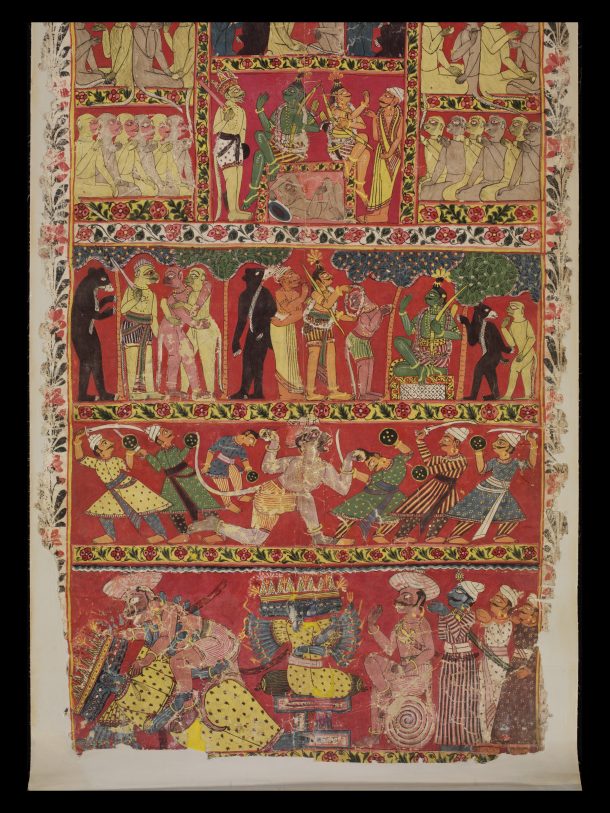

Hinduism has numerous gods and goddesses; its adherents have complex beliefs and forms of worship. Amongst the innumerable deities, Hanuman is most often referred to as the secondary central character in the epic Ramayana, renowned for his strength, military prowess and selfless devotion to the god Rama, prince of Ayodhya, India. Rama, the seventh incarnation of deity Vishnu, is the central character in the Ramayana. According to the Puranas, the ancient religious texts written between about the third and 10th centuries CE, Hanuman was the incarnation of Lord Shiva in his eleventh form of Rudra, the deity of wrath, to assist Rama with his struggle against Ravana, the ten-headed demonic king of Lanka. A scholar, a proficient musician, a dancer, and a valiant warrior, Hanuman is revered beyond the barriers of geography in South and South-East Asia. He is idolised for his bhakti (relationship between the devotee and the divine) to Rama.

In Hinduism, it is not uncommon for gods to appear as incarnations or composite beings. Hanuman’s monkey-like characteristics can be attributed to his mother, Anjana, a celestial nymph in monkey form under the spell of a curse. In Tantric form, Hanuman assumes the Panchmukhi form, the divine being with five heads – the heads of Hayagriva, Narasimha, Garuda and Varaha conjoined to his own .

The South and South-East Asian collection at the V&A holds over 500 bronze sculptures – several of which depict Hindu deities. In South India, the production of small-scale bronze figures of gods in large numbers is directly linked to the emergence of new devotional and ritual practices in India the early first millennium CE. The artistic production of cast-metal icons of deities thrived under the rule of the Pallavas (about 600-850/900) and the Cholas (about 880–1279). While some cast-metal icons were intended for use in religious institutions like the temple, most were intended for domestic worship. Some were made as Utsavmurtis – figures empowered through special rites to act on behalf of immovable images installed in temples.

Hanuman in the V&A collection

When investigating the history of objects from South Asia collected in Britain during the period in which large parts of India were controlled directly by the British Empire (between 1858 and 1947), we are faced with the inevitable challenge of confronting the attitudes of Victorian collectors.

At the time, British collectors frequently did not understand Hindu art, which was so different from what they were familiar with. Even prominent figures, including the art critic John Ruskin, and the Keeper of the Indian Museum at South Kensington (now part of the V&A), Sir George Christopher Molesworth Birdwood, held the opinion that Indian religious art was unable to represent living beings in their natural form, but instead they would be given a distorted or even monstrous appearance. For example, in the official handbook to the Indian collections at the South Kensington Museum in 1880, Birdwood states that “The monstrous shapes for the Puranic [Hindu] deities are unsuitable for the higher forms of artistic representation: that is possibly why sculpture and painting are unknown, as fine arts, in India”. Misconceptions such as these were not uncommon.

One of the earliest acquisitions of a figure of Hanuman into the V&A collection was recorded in 1869. This fine bronze figure from Sri Lanka was donated to the museum by a W. Morris Esq in 1869. The donor has often been believed to be the popular artist and designer William Morris, who was involved with the work of the South Kensington Museum (now V&A) at the time. However, it seems more likely that he was a government agent based in Sri Lanka with the same name. As documents for this period are scarce, this remains an open question for now. This figure of Hanuman was one of the earliest acquisitions for what would on to become the South Kensington Museum’s Indian sculpture collection. The worship of Hanuman spread to Sri Lanka from Southern India and this object was probably produced between the 12th and the 13th century for use in a temple dedicated to Vishnu. In this figure, Hanuman stands with his hand outstretched in the gesture of holding an object that is now missing. He possibly had a tray in his hands bearing the sandals of Rama or perhaps an oil tray that would be used in a lamp. His long tapering legs and slightly flexed knees emphasize his humility. His animal-like characteristics are portrayed in the muzzle with fierce canine teeth.

Some British people in the colonial government collected Hindu religious figures and other objects from India and other countries in South Asia. Lord Curzon of Kedleston assembled such a collection during his term as Viceroy of India between 1898 and 1905. A standing bronze figure of Hanuman from the 12th century, which used to be part of his collection, was loaned to the Bethnal Green Museum (where Young V&A is now located) from 1906, and later bequeathed with more than 200 other items to the V&A in 1927. The Curzon collection of Asian art was displayed in South Kensington in 1930 for 3 years. This sculpture was part of a group excavated at Coimbatore, in Tamil Nadu, South India, and would likely have been used as an Utsavmurti in processions and for worship in a temple. Except for his long tail, this bronze Hanuman is more human than simian, bending forward slightly with his hand in front of his mouth in his typical gesture of devotion. His rich adornments and short, patterned waist cloth make him more life-like.

Produced around the same time in two different areas of South Asia, both bronze figures show Hanuman in his role as a humble servant of Rama. Either flexing his knees or gesturing obeisance, Hanuman is represented here as a model for human devotion.

These two figures of Hanuman demonstrate how complex the history of an object and its acquisition for the museum collections can be. This will be a key topic that will be explored at V&A East Storehouse, opening in 2025.

In the next ‘Daily Devotions’ post, we will investigate some of the objects in the collection linked to Islam. You can read the previous post about daily devotions in Christianity.