We asked members of V&A East Youth Collective to find an object in the V&A collection that connects to their identity. For east-Londoner Haleema Ahmed, discovering a 19th century Pakistani spinning wheel led her on a journey to uncover her family’s relationship to textiles. She writes about how her identity has been shaped by the skills and knowledge passed down through generations.

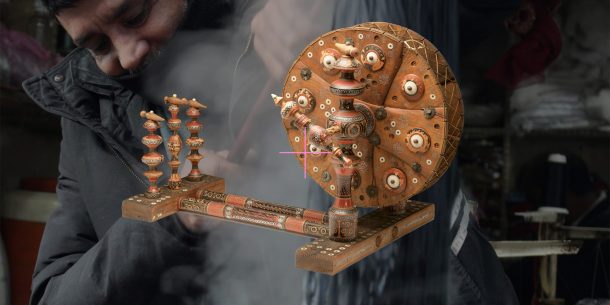

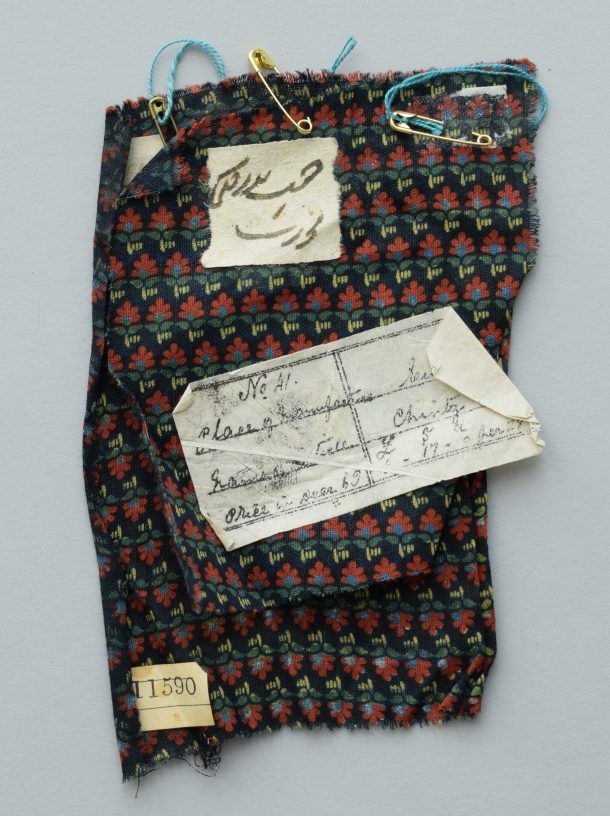

The objects held by museums are precious because they contain memories and experiences that weave people together. During my time on the V&A East Youth Collective, I was searching through the V&A’s vast digital database, Explore the Collections, and found a wooden wheel used to spin cotton yarn, from northern Pakistan, dating to around 1890. I enjoy sewing and learnt it from my mum and grandmothers. I thought this would be a great way to look further into my family’s relationship with textiles and our shared experiences of making across generations. I started by recalling childhood trips to Karachi…

Memories of Karachi

These practitioners seemed like magicians; able to fix or transform any item of clothing.

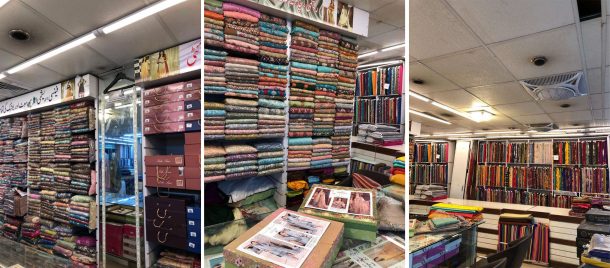

Textiles are a huge part of my Pakistani identity and one of my core memories from my visits to Pakistan. In the industrial city Karachi, there is a whole underground world, hidden from the scorching sun. A cave of treasures the size of a mini city, packed with fabric stalls as far as the eye can see. Here, you barter and haggle, fighting for the price you want. Rows upon rows of cloth, an overflowing abundance of textiles heighten the sense of possibility, the feeling of potential.

I remember being fascinated by a man embroidering. He had a vast expanse of cloth held taut and was crouched over it, in intense concentration, delicately adding stitches. The tulle fabric was being transformed into a bridal piece. Despite my love of these intricate embroideries, I had never thought about how much work went into it. It changed the way I looked at embellished pieces. Something that I thought was ‘pretty’ at a passing glance had now become a treasure, a piece to carefully examine and learn from.

Other vendors at the fabric market were selling lace, beads, patches, and dyes. The trimmings shop was a different source of delight. Full of laces, shiny ends, and jewels galore, it was my mother’s favourite stop. You could always transform an old suit into something new by adding a few ornaments here and there.

As we moved further into the market, a strong smell emerged, and I knew we had reached the dyers. Vast pots of mysterious substances surrounded them, with brightly coloured fabric hanging everywhere. Any stains could be removed, any colour that was desired could be achieved. These practitioners seemed like magicians; able to fix or transform any item of clothing.

A Conversation with my Grandmothers

Their stories showed me how strongly we are connected, even through parts of me that I thought were just mine.

I remember learning to first hand sew from my mother; we started with basic shapes using thick colourful embroidery thread. She would draw squares and rectangles and have my sister and I stitch over the pen marks with our needles. What my mum taught me, she learned from her mother. Both of my grandmothers have a history with sewing, so I sat with them to discuss their memories of it and how textiles and sewing formed a part of their identity.

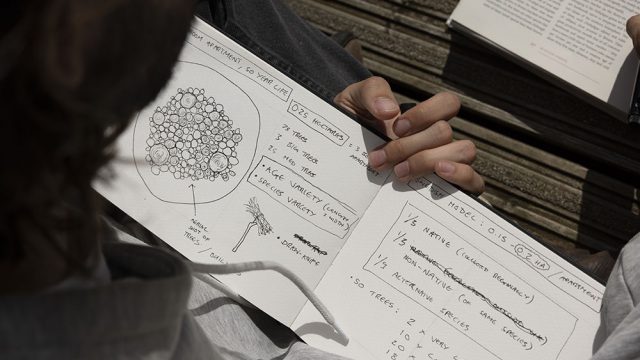

Seeing the fabric samples, my nano (maternal grandmother) remembers learning to pattern cut from her own grandmother. Back then, everyone used to make their own clothes and not many people bought ready-made outfits – or even went to the tailor! She recalls going to the fabric market with her parents and picking up whatever they needed at the time. She naturally learnt about material properties through those experiences, handling the textiles and noticing what was used in particular seasons. The first time I tried making a kurta (traditional Pakistani shirt) at home without help from my schoolteachers was with my nano. She guided me whilst cutting the pattern and helped piece it together, even inputting towards some of the design. It was a weird piece at the end, but I still treasure it because of its connection to my nano.

My dadi (paternal grandmother), on the other hand, was reminded of how she learned to sew. She observed the local seamstress and guessed how to cut fabric patterns, practising on her own and making mini mock-up clothes for her nieces and nephews, honing her skills. She did sewing jobs from time to time after migrating to the UK. She laughs whilst telling me that some of her relatives didn’t even know how to thread a needle, let alone sew! She was the go-to for learning some of the basics of sewing back then. When she got an industrial machine, she practised and taught herself the ins and outs of it. I still have her industrial machine in my shed but am slightly terrified to use it. The machine eats up the fabric with just a light touch; you must be careful not to lose your fingers!

I learnt many new stories about my family by tracing their memories through certain objects. Their stories showed me how strongly we are connected, even through parts of me that I thought were just mine. I hope to continue with this cycle of teaching and pass down my acquired skills and knowledge to the next generation so they too can be connected with their heritage.