A number of the textiles in the Fabric of India exhibition were made to be used in architectural contexts, whether as furnishings for buildings or as a type of portable architecture in themselves. As we didn’t have space in the exhibition to discuss these relationships, this blog aims to provide some additional context for those pieces.

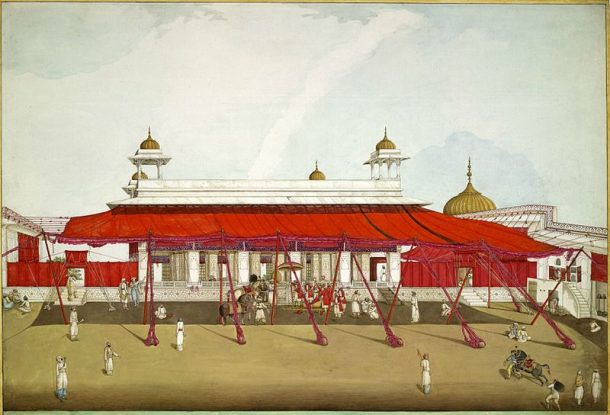

When we visit historic buildings in India today, they are usually empty shells which give no idea of how they could function as liveable spaces. The missing element is textiles, whether in the form of lavish furnishings and patterned clothing, or basic practical additions like awnings on the building’s exterior. Textiles can transform not just the appearance of a building but also its function. The awning added to the front of the building in the Red Fort in Delhi (shown above) provides shade for the building itself and the public space in front of it, and the cloth screens on either side both limit public access to these royal pavilions and also join them together into a usable suite of buildings – unlike the isolated monuments they appear as today.

The attachment of awnings (shamiana) to buildings was essential in India’s climate and the integral rings built into the walls of palaces, like these in Bundi (above), show that they were incorporated into the buildings at the time of their construction. The rings are visible in the photograph above the lower eave.

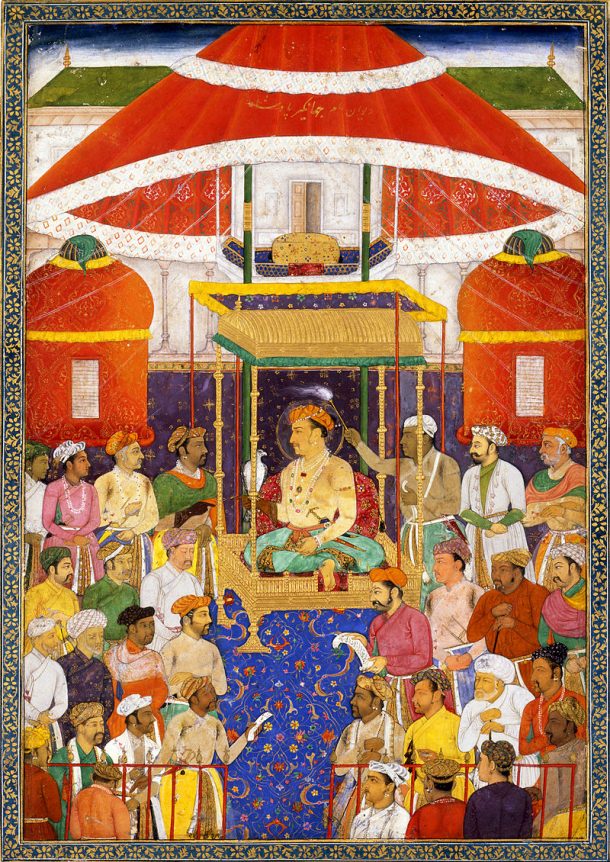

While the provision of shade and comfort were the prime functions of awnings and carpets, cloth screens functioning as moveable walls provided an important element of privacy, as well as shelter from north India’s chilly winds. These are called qanat (a Turkish word originally meaning ‘wing’) or parda, the Persian word for curtain, familiar to us today in the anglicised form of ‘purdah’ meaning female seclusion behind such a screen. Screens or cloth walls are also used to limit access to the ruler: in this painting (above), he sits at the centre of concentric layers of cloth. These are decorated on the inside with floral motifs which are found on both built and cloth architecture.

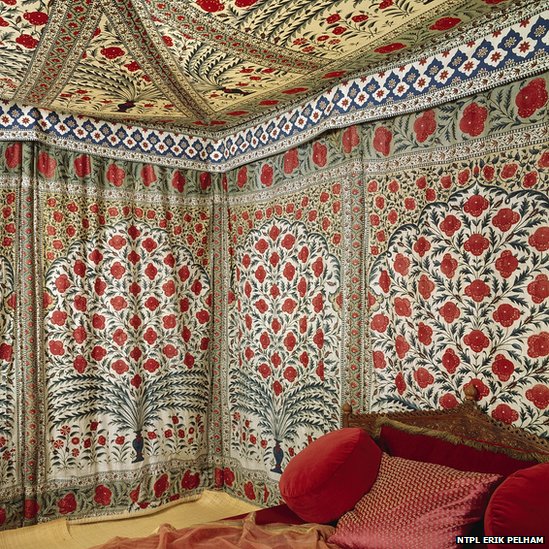

Flowers were used extensively on Mughal and Rajput buildings of the 17th century, and these patterns were echoed in the textiles that furnished them. The use of floral decoration reflected the Mughal emperors’ love of nature, but also embodied the idea of paradise as a garden: to be surrounded by flowers in a palace or mosque was to have a premonition of paradise.

Textile patterns painted on cloth attached to the ceilings of Himalayan monasteries such as Tabo (or sometimes on the ceiling plaster itself) replicate the designs of large canopies that were suspended below the ceiling, like the silk piece with Buddhist lotus design shown below.

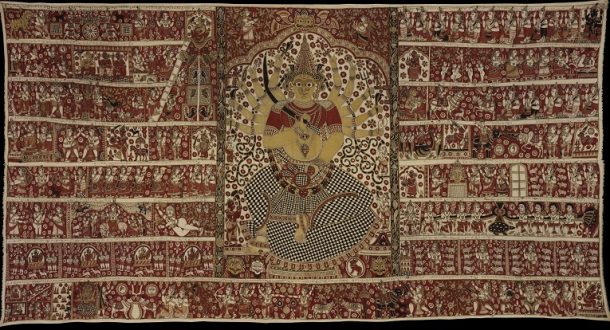

Narrative scenes painted on to temple walls also often echo textile forms. Horizontal registers showing scenes from epics like the Ramayana or stories of local heroes (often themselves deified) occur on both paintings and textiles, like the one below.

Cloth can also function as architecture in its own right, as for example in the case of tents. This 15th-century Chinese painting illustrates the story of a Mongol ruler who had abducted a Chinese princess, and this is his Central Asian encampment. It shows the same ensemble of a private tent, awnings and cloth screens that we see later in Indian images of tented enclosures.

The Mughal painting below shows how the emperor Jahangir combined the double or even triple-layered canopy associated with Mughal kingship with two round tents of completely Central Asian type. It’s not clear whether these two side tents performed any function other than as purely symbolic visual links to the Mughals’ Mongol ancestors.

In India, the tent became conflated with the ancient concept of the royal sunshade (chhatri) or canopy, and very often what we call a tent is more accurately a canopy combined with a cloth wall, as is the case with the splendid royal tent that belonged to Tipu Sultan of Mysore.

Free-standing temples and shrines can also be constructed from cloth. These create a temporary enclosure for worship of a local goddess, hung with textiles depicting the goddess and related deities. In the case of the Vaghri community of Ahmedabad, the reason for the outdoor, temporary shrine is that the devotees are from Dalit communities (once called Untouchables or Harijan) who were formerly prohibited from entering mainstream Hindu temples.

Textiles can provide exclusive spaces for both Dalits and kings, and can perform all the social functions that built architecture can, as well as some of the physical ones. The overlap between built and textile architecture is underlined by shared decorative imagery which blurs the boundaries between them, and practicality and beauty can combine to transform a bare stone building into a shaded floral garden. Architecture cannot function as a living space without textiles, while cloth has the capacity to create buildings on its own.