Carnival, an annual outdoor festival that includes processions, music, dancing and masquerades, goes as far back as a pagan festival in Ancient Egypt and exists in different variations across the globe. After a two-year hiatus due to Covid-19, Notting Hill Carnival is back this bank holiday weekend from 27 to 29 August and Hackney Carnival returns on 11 September. To celebrate this and to begin our research into carnival with a Caribbean focus for the Why We Make galleries at the V&A East Museum, we have invited staff from across the V&A to share their knowledge and experience of carnivals. What becomes clear is that the spirit of subversion and freedom connects the complex and diverse histories of carnival across time and place.

Avril Horsford, tour guide of the Historical and Hidden Caribbean Tour

Every aspect of this costume amplifies its origins in Caribbean history. Designed for ‘Play Mas’, a political comedy set during a frantic carnival period, the cloak aims to capture the truly theatrical nature of carnival. The costume is also a fine example of a Caribbean cultural development, borne of necessity, namely the importance of recycled or ‘found’ objects to Caribbean creativity. Examples are included here in the form of bottle-tops, mirrors, and buttons. This cultural signature reached its peak in the iconic Steel Pan music, which was originally played on discarded containers that were ‘found’ and remodelled into musical instruments. The Caribbean’s Steel Pan music has come to typify the carnival spirit internationally.

Dan Vo, volunteer LGBTQ Tour Coordinator

This queen costume, by Ali Pretty and Ray Mahabir for ‘Call the Rain’, was inspired by the opening words of a poem by lesbian author Jeanette Winterson in her book ‘Art and Lies’, which includes the poet Sappho as one of the main characters. The costume won first prize for best design at Notting Hill Carnival in 1998.

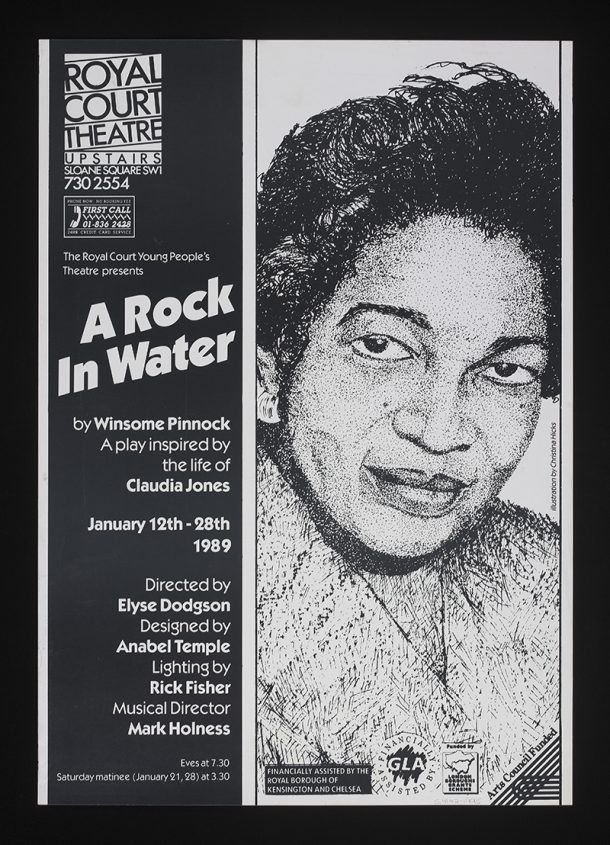

Jacqueline Springer, Curator Africa & Diaspora: Performance

Carnival is an inheritance. From that which exists, in expressed contexts, in different regions and countries throughout the African continent. It is an inheritance adapted by those enslaved in plantations in regions within countries across the waters from that continent. Carnival is also subversion: adaptations to the inheritance – coalescences of cultures of the enslaved, of their enslavers – reflect fortitude and the rejection of racialised violence and supremacism in plain sight. Claudia Jones, Rhaune Laslett and Russ Henderson knew that the foregrounding of cultural practice(s) would speak to the inheritance, the adaptation and the subversion on British soil.

Serenella Sessini, Assistant Curator, V&A East Storehouse

Renaissance Carnival

“How lovely is youth in its allure,

Which ever swiftly flies away!

Let all who want to, now be gay:

About tomorrow no one’s sure.”

These are the opening words of ‘The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne’, a song written by the Florentine ruler Lorenzo the Magnificent for the carnival of 1490, as translated by Jon Thiem in his 1991 edition of Lorenzo’s works. During carnival men dressed up and wore masks, sometimes representing mythological figures like the god of wine Bacchus and his lover Ariadne, and paraded through the streets of Florence on decorated floats in the shape of chariots, called ‘Triumphs’.

Carnival was the only time of the year when official rules and roles could be subverted. For example, images of the ‘Triumph of Love’ from this time include legendary scenes of role inversion as examples of the power of women. In these, women manage to break their conventional social position and finally rule over men, made weaker by love. The object shows the Biblical woman Delilah cutting the warrior Samson’s hair while he is asleep to take away his power and a woman called Phyllis riding on the back of the wise philosopher Aristotle as if he was a horse.

A similar object shows additional scenes or role inversion, such as Queen Omphale holding the hero Hercules’ club while Hercules himself is dressed as a woman and is spinning wool, and the daughter of a Roman emperor ridiculing the poet Virgil by leaving him hanging halfway to her bedroom’s balcony inside a basket, for everyone to see.

Anastasia Misirli, volunteer in Visitor Experience

Going to my favourite theme party ‘Wigs & Glasses’ of the past year, I chose to dress-up with ‘Jester’ glasses. A jester was the person who used to entertain others. The ‘Jester’ glasses let me look at life through the lens of joy, fun, and laughing, and gave me a chance to free myself from daily ‘mask wearing’. The waves symbolise the different ‘waves’ of feelings and moods during carnival season. Carnival equals approval and acceptance of our true self!

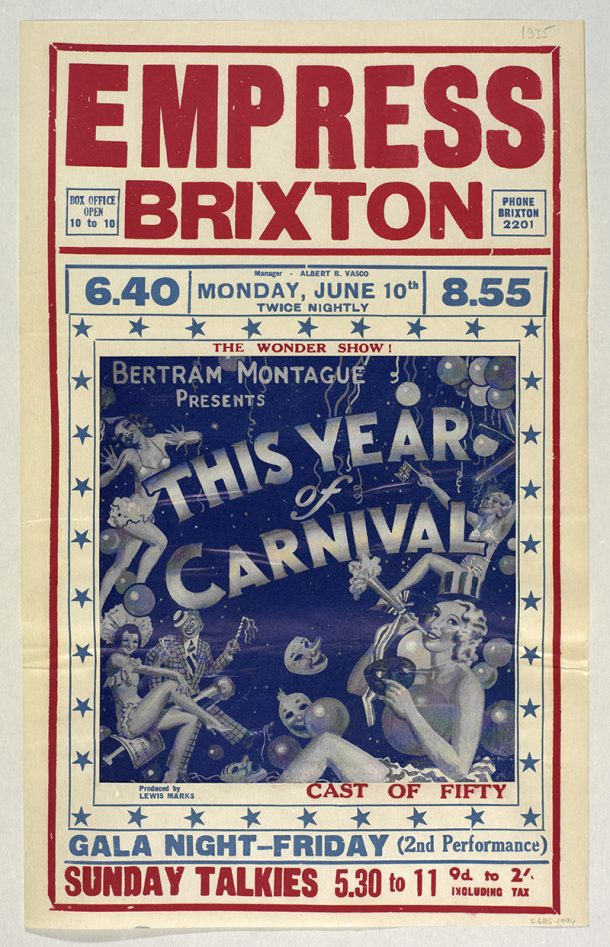

Cathy Haill, Curator of Theatre & Performance

This wonderfully exuberant poster illustration, with its showgirls, check-suited comedian, balloons, party poppers, carnival masks and bottle of champagne, appears to be enticing audiences to the best New Year’s Eve party in June. In fact, it advertised the twice-nightly mammoth revue ‘This Year of Carnival’, starring Lalla Dodd and George Doonan, at the Empress Theatre Brixton, for the week of 10th June 1935. It opened with the all-cast number Gay Carnival, closed with Spanish Fiesta, and featured sketches, songs, music, and dance numbers by The Gordon Ray Girls – just the kind of show in which the Empress Theatre, the impresario Bernard Montague, and its producer Lew Marks specialised.

Originally built in 1898 as The Empress Theatre of Varieties, the theatre was enlarged and rebuilt in Art Deco style in 1931 to seat over 2,000 when it was acquired by Variety Theatres Consolidated. The advertisement on the poster of Sunday Talkies, however, foreshadowed the ultimate fate of the theatre and large variety shows, however glamorous. The Empress was converted into a cinema in the mid-1950s and demolished in 1992.

Martina Maggioni, Visitor Experience Assistant – Sales

Theodore Viero, the artist of this elegant print, was from Venice. For six months each year, including during the carnival season, all Venetians were permitted to disguise themselves by wearing a black silk domino cloak and a white mask, often with a black tricorn hat. Venice for me is fantasy, obsession, beauty, art, comfort, home.

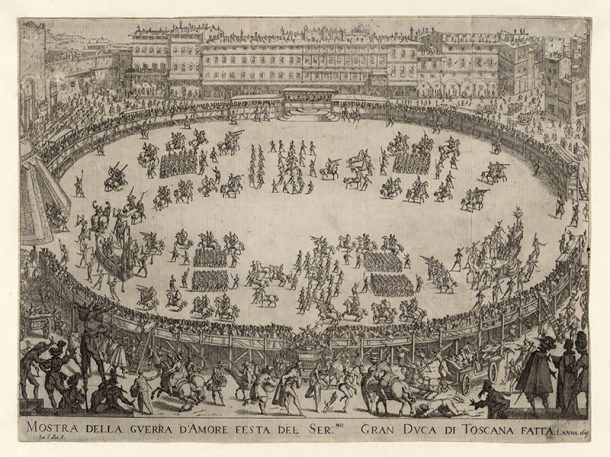

Elaine Tierney, VARI Teaching and Training Co-ordinator

This print shows a festival – or spectacular performance – held in Piazza Santa Croce in Florence in 1615 as part of the city’s carnival celebrations (carnival in this context means the period before fasting for Lent officially begins.) As a historian of festivals, it strikes me as a rather odd image. We tend to think of carnival as a form of celebration ‘from below’ – a popular, uproarious, sometimes unruly repost to rigid societal norms. By contrast, Jacques Callot (the artist) emphasises the court spectacle at the image’s centre, which is encircled by temporary grandstands for the better-sort of spectator. This makes sense if we think about the print’s purpose. Other versions of the same image illustrate printed descriptions of the event, a choreographed tournament starring Cosimo II de’ Medici, ruler of Florence. And yet, if we look more closely, Callot’s scene is imbued with the spirit of carnival. We see people buying snacks from pedlars, scrabbling up ladders to catch a glimpse of the performance and watching from nearby rooftops. Others are simply trying to get on with their lives in the vicinity of a big outdoor celebration – something that will feel only too familiar to 21st-century city-dwellers!

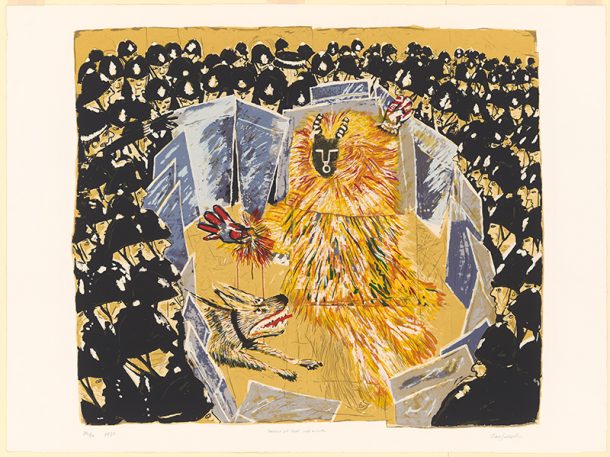

Federica Ionta, Visitor Experience Assistant

This print by Tam Joseph, through its affective visual language, taps into cultural and social aspects related to the carnival, addressing topics of public order and resistance. Depicting this scene, his visual commentary is concise yet eloquent.

Nkechi Noel, African Heritage Tour Guide / Guide

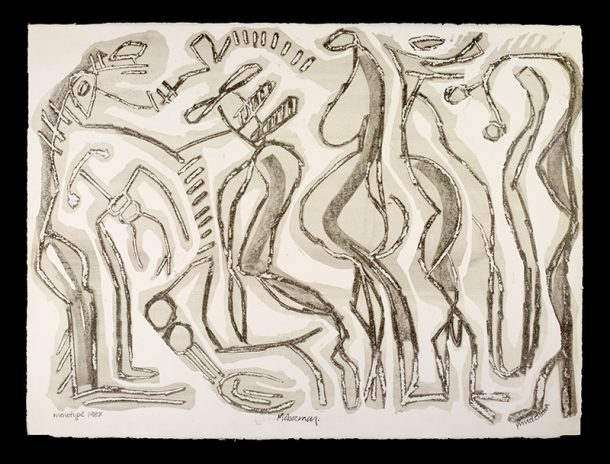

This print on ink with wax crayon by Timo Lehtonen evokes a sense of freedom of expression that myself and my friends felt when going to carnival. The mass gathering at carnival was always a mash up of music, food and catch ups! When dancing to the beat back in the day, there were no restrictions on where you could go. The only restriction was how long your feet could sustain you to dance. So, this work speaks to me because carnival can be a creative space to connect and belong.

Pennie Mendes, Volunteer Tour Guide for the African Heritage and the Historical and Hidden Caribbean Tours

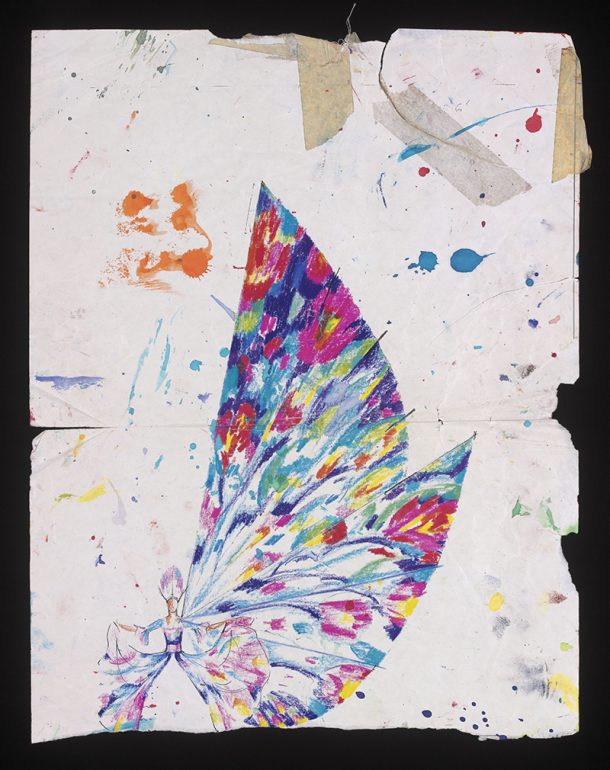

Trinidadians will claim the annual carnival in their country is the best in the world. Although I am not a Trini myself, I wholeheartedly agree, as I had the privilege of working with Peter Minshall (colloquially known as ‘Mas man’) in the ‘80s and ‘90s. His extraordinary spectacles of living art tell stories to an appreciative crowd along the streets of Port of Spain on the two days before Ash Wednesday. The carnival bands’ masquerades are led by a king and queen in spectacular kinetic sculptures, who had already taken part in the ‘Dimanche Gras’ competitions the previous Sunday. The procession of thousands gradually climbs the Savannah stage to give a full-blown theatrical performance as a breath-taking grand finale. By then, the euphoric roar from the audience is tangible and Minshall’s Mas becomes high art. The V&A holds the design for his queen ‘Joy to the World’ for the band ‘Hallelujah’ from 1995 – Minshall’s magnificent celebration of Caribbean identity.

Living in such an ethnically-mixed country as Trinidad, with the majority of people proudly collaborating to realise the carnival, taught me so much about the strength and determination of people in the Caribbean, the country’s precarious history and its struggles to create its own culture. It also taught me the meaning of equality, freedom, brotherhood and sisterhood while involved in such productions. The bands I assisted in producing for Peter Minshall were ‘Papillion’ in 1982 (on the ephemeral nature of life); the first two parts of his infamous ‘River’ trilogy from 1983 (on the power of capitalist technology to destroy livelihoods and homelands); ‘Callaloo’ in 1985 (on the clash between good and evil); and ‘Rat Race’ in 1987 (on the endless and futile pursuit of power). As part of a small entourage of performers and technicians in 1985, I visited Washington, D.C. with Minshall’s grotesque kinetic sculpture ‘The Adoration of Hiroshima’. The costume portrayed the ludicrousness of nuclear weapons and took part in a peace march on the 40th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima.

For many decades carnival (or Canbouley as it was originally called) was very much a local event. Unfortunately, in the 21st century it is becoming more and more catered to tourists whose all-inclusive itineraries separate them from the locals. Many band leaders now have their costumes made in Asia. We have to preserve the historical context of the world’s greatest carnival and what better place than in a museum?