This little blog post is on the importance of looking at the back of objects, as they can teach us a lot…

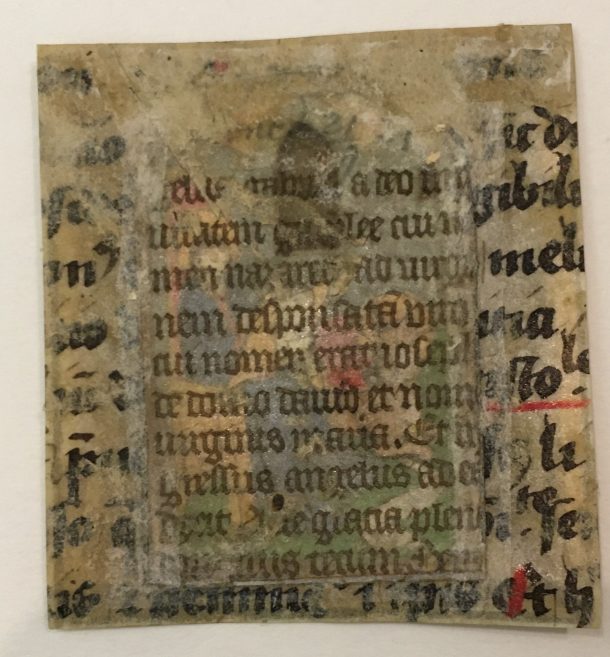

The small miniature above, currently on display in room 90 as part of the Fragmented Illuminations exhibition, shows the evangelist St Luke writing the gospel in a vaulted room. A curling scroll spells out his name in French (‘s. luc’), and the ox, his symbol, rests by his side. The style of the miniature would indicate that it was painted around 1420 – 30 in Paris. Such a scene would typically be found in a book of hours, introducing a passage from the Gospel of St Luke. Books of hours were the most common type of prayer book in Western Europe in the late middle ages. They contained a number of core texts, including excerpts from the four Gospels.

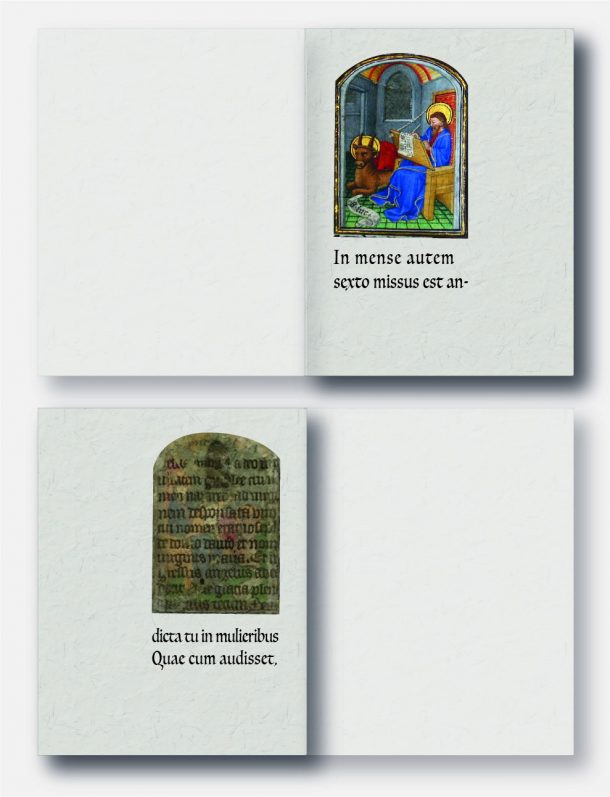

At first sight, this piece appears to consist of one small cutting, measuring 47 by 44 mm. One should however, when possible, always examine the back of things, as it may tell a different story. In the present case, the reverse is full of surprises, as it reveals that what we are looking at is not one cutting, but two.

The minute Gothic script on the back of the arched miniature contrasts with a thicker script written on a clearly different piece of parchment, from a different manuscript. I have not been able to recognise the text from such a small sample, but it dates from later in the 15th century, judging from the script. It would seem that it has been used to somehow expand the St Luke cutting, allowing for a frame to be painted around it. The motivation behind this painstaking operation may have been to make the painting look more substantial, and to make it squarer – possibly to fit into a small locket, or for a frame. It is difficult to establish when this was done. The joint between the two parchment pieces has been consolidated at a later date at the museum, with a semi-transparent paper tape.

The text in the central section contains, as expected, a portion of St Luke’s Gospel, which indicates that the miniature once featured on the recto (or front) of the leaf it belonged to. We can actually read full sentences from the Gospel, which span verses 26 to 28 of chapter 1. The beginning of verse 26 (‘in mense autem sexto missus est an[…]’) are missing: they would have been written under the miniature on the recto. One can catch a glimpse of writing at the very bottom edge of this cutting, below the thin gold frame. This text is an account of the Annunciation, the passage from St Luke’s Gospel that was commonly used in books of hours. This leads us to conclude that the miniature came from a very small book of hours. Below is a tentative reconstruction of the leaf layout. The recto probably had a decorated border painted on the three outer sides of the page.

This piece was acquired by the museum in 1883 as part of a large group of manuscript cuttings bought in batches from William Henry James Weale, a leading scholar of early Netherlandish painting who would later become Keeper of the museum’s library from 1890 to 1897.

No other cuttings from this book of hours are today known to survive, but they may yet emerge on the art market, in a public or private collection…