At the core of Gayle Chong Kwan’s practice is an expanded and embodied notion of photography. The work that she is developing as Artist in Residence in Photography at the V&A, on the theme of ‘Capturing Motion’, is focused on a critical engagement with objects in the V&A’s collection through experimentation, participation, and movement.

Photographs, as all objects, are not static. They move around us, and in us, as we move through them; as material that is lived in different moments, through their provenance, and as things that are alive in meaning. A more contingent, embodied, and relational articulation of things in relation to people, place, culture ,and beliefs, can only improve and acknowledge the reality of our relationship with objects. I am interested in exploring movement, not as a representation or something that can be ‘captured’, but as a shared process.

My focus is on the activities of transportation, protecting, cleaning, conserving, object acquisition and disposal, and actions that manage the insects and moths that threaten them. I have been taking photographs and collecting objects related to these processes, which I am using to develop a series of three-dimensional photographic collages that will be worn by people on walks through the museum. These three-dimensional photographs will both alter the view and movement of the wearer – as well as change and interrupt the spaces in which they move.

My research, and the work I am developing at the V&A, connects with my wider art practice, which has often focused on sensory rituals, participation and events, and also with my PhD research in Fine Art Practice at the Royal College of Art around the notion of ‘Imaginal Travel’, which I define as an active mode that is both internal and shared; an attitude of curiosity; an intensity of experience; and defined in terms of shifts in scale and attention to detail.

I have been researching in the collections and archives, and spent time with people in different departments at the V&A in the first few months of my nine-month long residency here. This has included going on walks, looking at objects together, observing the start of the movement of objects from Blythe House to the new buildings in East London, and participating in the laying and checking of insect and moth blunder traps in the museum’s different locations.

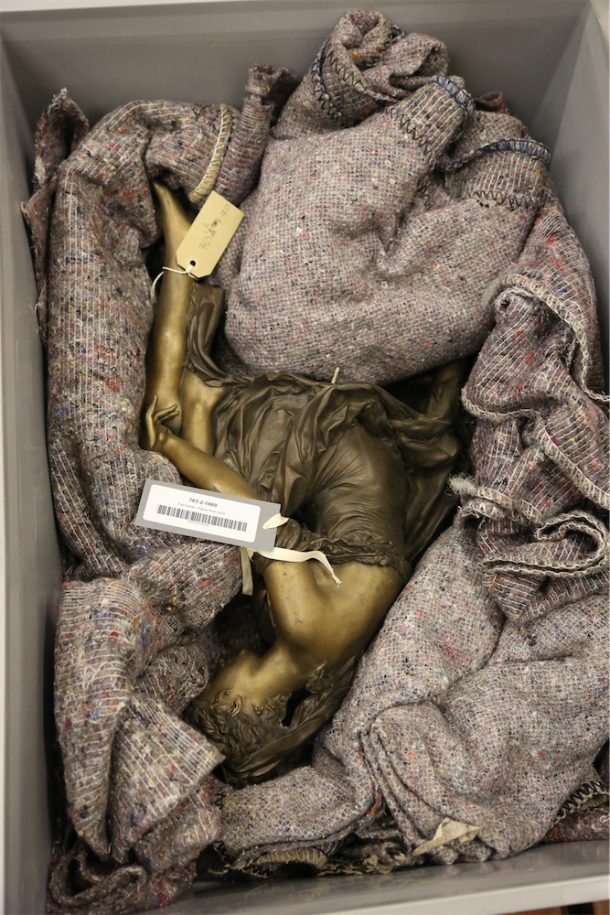

I have been up on the roof at South Kensington, been involved in developing a Pop-up Performance, and run workshops that explore the senses, public space, and movement. I have taken my camera with me on all my activities, and have a series of photographs that inform and form the basis my three-dimensional pieces. The photographs I have taken, including this one while walking and talking objects in the collection with Glenn Benson at Blythe House, speak to me about how the materials and objects that surround, pack, protect, or are considered secondary to the collection objects, are as present themselves.

I was particularly struck by how tender the folds of the protective blanket are in relation to the bronze figurine, which seems curled up in it, like a sleeping cat that has found its nook of comfort and security.

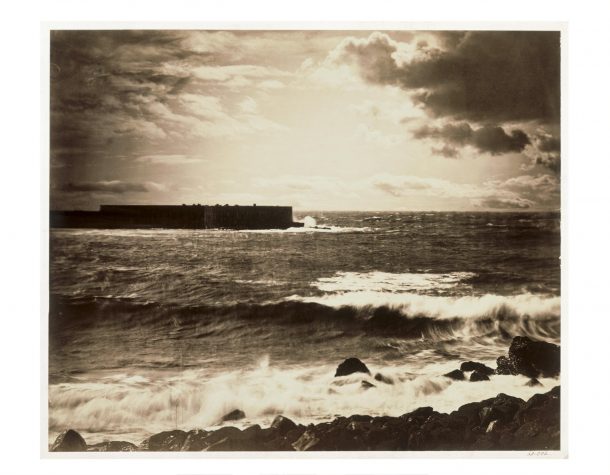

I have long been obsessed by a photograph in the V&A’s collection that has followed me throughout my artistic practice, or perhaps I have followed it, coming at it from different angles at different times and in relation to artworks I have been making. ‘The Great Wave’, made in 1857 by Gustave Le Gray, is a pivotal photograph for the work, which I am developing during my residency. It looks like an innocuous landscape of sea and sky, yet in its time it was radical in its construction and, for me, it articulates an essence of montage/collage, in that it brings together two different moments in one photograph.

In the mid nineteenth century photographers found it almost impossible to achieve tonal balance in the exposure for both sea and sky in a single picture, as the sky was usually over-exposed. What Le Gray did to overcome this was to make one print from two separate negatives; one exposed for the sea, the other for the sky. This horizon-in-transit, sitting between different technical aspects and between moments in time, as well as environmental designations of sea and sky, is a way in to thinking about movement being part of objects themselves.

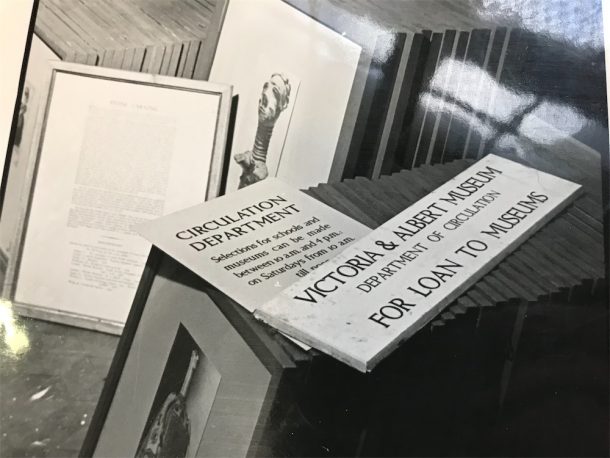

Much of my initial research has been on the Circulation Department, which existed from the 1850s until its closure in 1977. The history and ethos of the Circulation Department provides has given me a way to explore how objects move in relation to the V&A itself. The archives of the Circulation Department, currently housed at Blythe House, have been fascinating.

The origins of the Circulation Department can be traced to 1850, when travelling collections of works of art established by Central School of Design, Somerset House, were lent on rotation to provincial schools. In 1852 a ‘Circulating Museum’ was created when 600 objects were sent in specially created railway truck around the country. Over 4 years it was seen by 307,000 people. The second Circulating Museum, in 1860, involved 900 objects and was seen by 429,000 people. It was the first ever ‘travelling gallery’ in the UK; it loaned both original works and copies to provincial and national museums, libraries, and galleries, art schools and schools; it placed an emphasis on collecting contemporary work, and amassed around 32,000 objects. I have been particularly interested in photographs that recorded the activities and people who worked in the department; it had a higher than usual intake of women and art school educated staff. Some were also members of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

Because my practice straddles multiple disciplines, and the work I make does not neatly fit into categories nor mediums, I have been excited to encounter works in the V&A collection that bridge photography, the body, and movement. The Naked Dress, 1972, by Floris Neusüss and Renate Heyne, is a photogram printed on linen, which although credited just to Neusüss, was created by Floris and Renate. The shape of Heyne’s body is printed on both front and back, and she wore it on a number of occasions. It is a wonderful example of a work that comes alive with movement when worn.

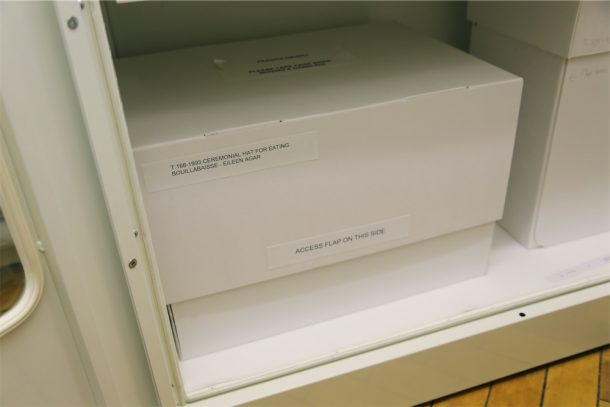

I came across another work that also straddles art and performance (as well as the body, and Surrealism). Eileen Agar’s Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse, 1937, is made of cork, coral, sea shells, fishbone and sea urchins. A British Pathé news item exists in which Eileen Agar walks the streets of London wearing the hat. I adore the way in which landscape and the senses are ‘worn’ on the body, and how the work changes the feeling of the wearer – and the way in which the wearer is viewed. Due to the fragile nature of the materials used in its construction, it wasn’t possible to view the work ‘in the flesh’, but I was excited to encounter it in the box in which it is housed in Blythe House.

For me, the box becomes a frame through which the work can be imagined, its shape and scale perceptible from the white cardboard box encasing it. The work, worn so proudly and playfully by the artist, becomes a box that – for the foreseeable future – is framed and fixed behind its protective cipher.

Gayle Chong Kwan continues her residency until July 2020. For more information visit our residencies page.

See more on Gayle Chong Kwan’s website.