Hoda Afshar is an artist and lecturer born in Iran and now based in Melbourne, Australia. Working across photography and moving image, her work explores the nature and possibilities of documentary image making. Focusing on issues of representation, marginality and displacement, Afshar employs processes that disrupt and play with traditional image-making approaches, merging aspects of conceptual, staged and documentary practice.

A transcript of a talk held between Iranian artist Hoda Afshar and Shoair Mavlain, director of The Photographers’ Gallery, this post marks the acquisition of nine works by Afshar, from her series ‘Speak the Wind’, which will be on display in the new Photography Centre in May 2023.

Shoair Mavlian

Before we start talking about your work, I wanted to ask about the context in which you grew up. How did that impact the way that you think about photography, the way that you think about images and influence your practice?

Hoda Afshar

My upbringing and the context that I grew up in played a huge role in how I became interested in photography and how I go about making images today. I was part of the first generation born in Iran after the 1979 Revolution, which radically transformed the country and its social and political structures. Basically, my generation grew up with two identities, and the necessity of having to ‘perform’ these identities. We knew that certain things could not be shown or talked about outside the house – how we appeared in public was in marked contrast to the reality behind closed doors – and in terms of art-making and so on, only specific modes of representation were allowed. We also came to understand that how we appeared to the outside world – outside Iran that is – was increasingly determined by this image. So when I discovered photography at school I was excited about the possibility of capturing some of those aspects of our social lives that were hidden, as well as the possibility of using photography to challenge dominant representations.

The idea of performance runs through all of your work, and I think it’s a really interesting way to challenge that experience of bringing the camera into a space where it’s unwelcome. I wanted you to speak about your interest in performance in general outside the photographic space, and how you think that’s influenced the way that you’ve made work.

I initially wanted to become an actor. In Iran, before you go to university, you have to sit an exam and nominate five course preferences in order, and you have no choice but to study whatever course you get into. My first preference was theatre, and my second was photography. I got into photography. For the first few years of my course, though, I was constantly photographing my theatre friends’ performances. I was obsessed with theatre, and somehow I think that this really influenced the way that I think about photography.

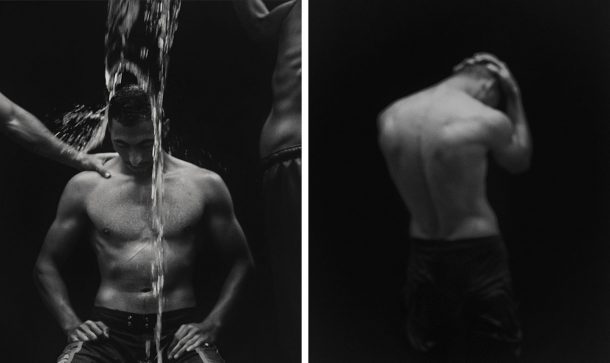

At the same time, I think there is something inherently theatrical about photography – especially photography that aims at telling a story – in that you have to choose what to include in the frame and what to leave out. Like the theatre director, the photographer makes decisions and must intervene in a scene in order to interpret what she sees in front of her; and quite early in my career I became interested in the idea that a documentary approach that involves stagingcertain elements may in fact be a way at getting to the heart of a story. For example, I like to work with photographic subjects as though they are actors telling their own story, involving them in the process in a way that gives them greater agency, and reveals more and more layers.

Your new work Speak The Wind (2022) is quite a shift from the bodies of work you’ve previously made, both visually and conceptually. This is a really incredible new project; your first published photo book and I’m really excited to hear you speak about it.

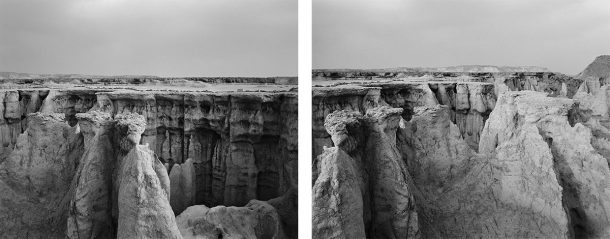

The work was made over five years in the islands of south of Iran, in the Persian Gulf region, in the Strait of Hormuz. That whole region has been an important site of trade, exchange and political tensions for centuries, and it continues to be. But it was not this first project that drew me there.

I first travelled to the islands in 2015. At the time I was going through some difficult life experiences, and a friend of mine told me I should go there, explaining that the place has magical healing powers. I didn’t know what she meant, but I got on a train and travelled 18 hours from Tehran.

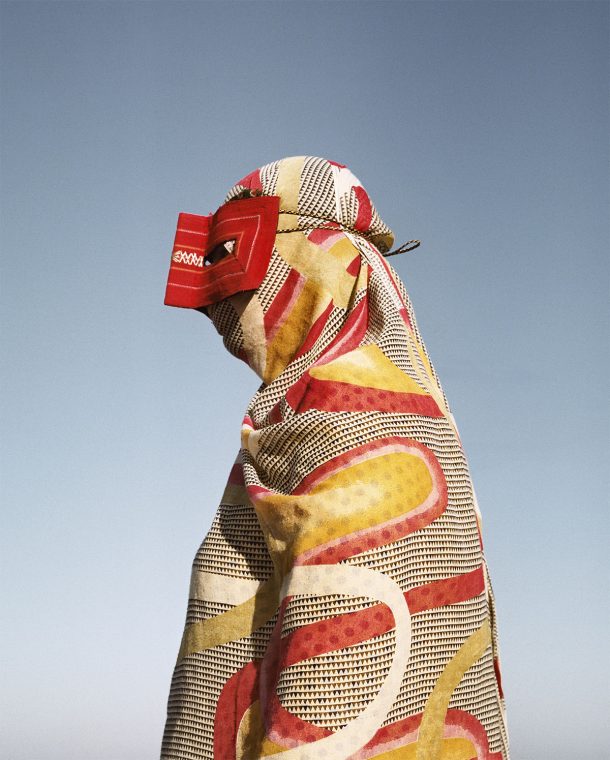

I immediately fell in love with the beauty of the landscape, and I was struck by the stories that people shared with me. They explained, for example, that the region is inhabited by living winds that come from East Africa. I was told that those winds can possess a person, and that they possess women more than men; so women wear a distinctive mask that has a thick moustache and eyebrows to trick the winds and protect themselves. They explained how the winds have shaped the landscape and where particular winds live, and I was introduced to the rituals related to the experience of spirit possession.

From that first trip I knew I would have to return, which I did, again and again, becoming more and more immersed in the culture, while of course taking pictures. The idea of the work gradually took shape over time, and all of the themes I have mentioned already are woven in there.

I remember I came to visit you when you were editing the book and you explained to me how you wanted it–- all those stereotypes and ideas that you were trying to challenge. Can you tell us more about the conception and structure of the book?

At first, before the book idea was conceived, I just took pictures, as you do as a photographer, intuitively, recording what I was seeing. I didn’t intend to make anything out of it. But then I started looking at the history of the region, and the more it revealed itself to me the more it entranced me. As an Iranian, I was not aware of the centuries-old slave trade in my country and the huge population of Afro-Iranians living there. That history remains silent. Slavery only ended in 1927, and the majority of African people drifted to the islands because they couldn’t mix with the population in other parts of the country – they were subjected to severe racism and prejudice, and had to deny their identity, their African identity.

And then there is how this history connects to the belief in possessing winds and the related ritual practices, the origins of which can be traced back to Africa. This history is still mostly unspoken, or it is not known about, or it is denied. It’s a complex issue, and very few Iranians, much less outsiders, have much idea about it.

So when I started seriously thinking about the book, I thought about how to go about describing this history, what visual language and structure to follow, and so on. I knew from the start that I did not want to take a straight documentary approach, to the extent that this would involve explaining these experiences and beliefs in terms of something more concrete, more real. Instead then I took as my starting point my own experiences on the islands, and all those stories related to me by the locals, and I tried to reimagine the history of the winds themselves, and all the ways they have shaped the islands.

At the same time I thought important to consider how such a book would be received, that is, how to communicate all this for an outside audience, and in a way that avoids repeating the usual stereotypes, which can be difficult when presenting such work.

Agreed. I remember thinking ‘I know what press image they’re going to use for the book, for the exhibition and for any news article that’s ever published about this body of work’. Can you speak about that, about the predictability of curators and media agencies in representing your work?

Absolutely, it’s inevitable, and you have to work with this understanding. For example, in the book I paired the profile picture of the woman in the veil with the image of the red road that leads to the source of the ochre that women on the island use to colour their clothing. This is one of the themes in the book – this connection between the culture and the landscape of the island. At one point, I considered removing the pictures of women in veils from the book because such images tend to get fixed on by western audiences and overdetermine their readings. Obviously I abandoned this idea, as it would have involved removing the very people whose experiences the book is about, but your example does illustrate the problem.

You do what you do, and you make what you believe in. I tried to bring out the complexity of things in the narrative structure and design of the work, partly in an attempt to challenge the viewer to look beyond the surface; but ultimately it’s up to audiences how they want to read it.

What I think is fantastic about your work is how you can investigate so deeply into specific subjects, reveal what you feel you need to reveal and then move on to something different.

Thank you. At the heart of everything I do and make is this curiosity about the relationship that photography has with visibility: with what is seen or, in the present case, what can be seen. That is why, in Speak the Wind, the wind is not only the explicit subject matter of the work, but it also serves as a sort of metaphor that speaks to the possibility of capturing or recording certain experiences and stories. Researching and making this work was certainly a revelation and opened up new directions that I look forward to exploring in the future!

Interview transcribed by Marie-Luise Mayer.