What interests you about the V&A?

Despite living on the other side of London, the V&A is the cultural place I’m most drawn to. The geekiness emanating from every object in the collection has a magnetic pull over me! I could spend hours looking at the intricate decorations on wooden cabinets, or the wrinkles on meticulous replicas of ancient statues.

I admire how the V&A is embracing digital creativity with a refreshingly critical approach. The 2016 Bot Summit at the V&A inspired me to create several twitterbots, and to teach non-technical audiences how to make their own.

One of those bots caught the attention of the Digital Team in the V&A’s Learning and National Programmes Department, and so I was invited to use the museum as a playground for workshops that give young people a glimpse of what UX designers and game developers do, as part of the Samsung Digital Classroom.

When I learned about the Videogames exhibition and the residency linked to it, I knew I had to apply! As I wrote in my blog, I’ve been flirting with game-making since I was 11. I learned to code so that I could cobble together videogames. I’ve been building digital toys and teaching game design at universities around the UK for about 10 years. This residency at the V&A will enable me to continue my research and experimentation into game-hacking, both as creative and educational practice.

Tell me about your creative practice and the thinking behind it.

Hacking is a word that received a lot of bad press, but I refer to it as the practice of modifying something, either to repurpose it or to subvert it. As Mackenzie Wark put it in A Hacker Manifesto, creativity to me means “hacking the new out of the old”.

Creating by hacking is an iterative practice, and there are two phases to each loop:

- Decoding: No matter what the subject of a hack is, I start by taking it apart both conceptually and materially. By doing this I can understand how it works, and see its moving parts. For example, when I hack traditional boardgames, I begin by deconstructing the mechanics of a game. By isolating one rule or removing one component at a time, I can document how it impacts the game system and the play experience.

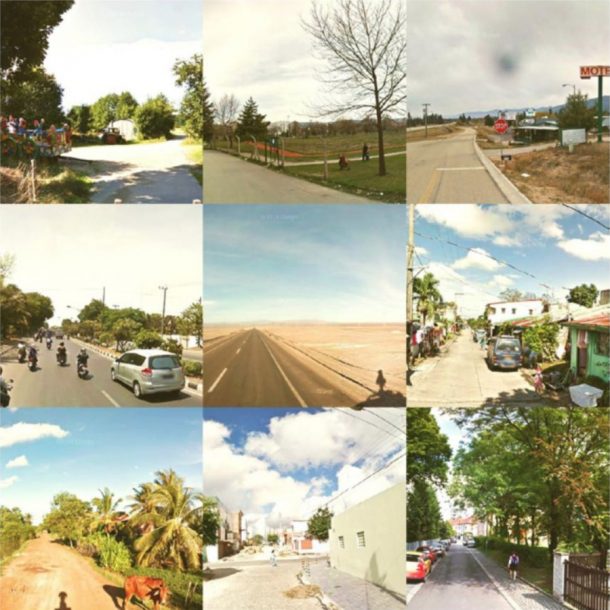

- Encoding: I can then put things back together. Instead of restoring the original order, I inject my subject with a new purpose, I recombine its parts, or I mash up different hacks. For instance, @somewhereBot repurposes Google Street View images, combining them with procedurally generated musings about the weather in random places.

Bot on a roadtrip, pictures by Google Streetview, composition by Matteo Menapace

So how do you get a beginner excited to make games?

Hacking an existing game is a great gateway into game design. You don’t have to start from scratch, but you can subvert a game into something very different and very personal.

In the last year I’ve been teaching gamedev at Goldsmiths and Ada College. My courses start from game design fundamentals, which students practice by making boardgames. This is because making boardgames is quick, collaborative and accessible: there are practically no barriers to entry. Once they have made some boardgames and began to see themselves as game designers, students can transfer skills and knowledge from analog to digital game-making.

What is your focus for this V&A residency?

Game-hacking, of course. Both as creative and educational practice.

I will facilitate game-hacking workshops to seed the idea, in as many people as possible, that they can move beyond just consuming digital entertainment and become game makers.

And I will hack games, drawing inspiration from social issues and current events to provoke what I call Minimum Playable Dilemmas: presenting players with uneasy choices that question their ethics. For instance, a game that lets you explore the impact of your food choices on other people and the living planet. Or, a game inspired by Uber greyballing (the systematic evasion of law enforcement through a technology that identifies and deceives what Uber calls opponents), in which one person plays Uber, the other the opponents.

I want to disseminate minimum playable dilemmas as part of the disrupt strand of the Videogames exhibition, and invite visitors to both play and hack them.

_____________________________________________________________________

If you would like to visit Matteo and hack some boardgames visit him during one of his open studios.