An investigation into the materials used to create the watercolour of this Tudor royal palace.

A little gem passed through the V&A Science Section at the end of 2016: the drawing of Nonsuch Palace by Joris Hoefnagel.

Henry VIII started building Nonsuch Palace in Surrey in 1538 to celebrate his 30 years of reign, and the birth of his long-awaited male heir Edward. It was intended to be his grandest, most lavish palace, without equal (hence the name ‘None such’), built to match the French king’s Chateau de Chambord.

The palace no longer exists – although you can still see the outline of its foundations from the air – and we now only have very few drawings that record what it used to look like. I was asked to investigate the materials used to make the Hoefnagel watercolour, and I set out to do that by using the best non-destructive, non-intrusive scientific techniques available at the V&A.

The first thing I wanted to check was the wonderful dark blue pigment used to render the plasterwork on the south façade of the palace.

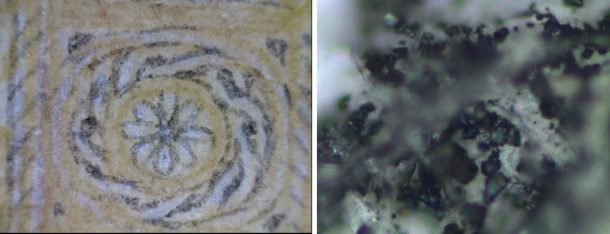

And this is where I had my first surprise: under the microscope, the dark blue outlines of the figures were not blue at all, but black! Our visual perception of the black pigment (which I identified as carbon black) is altered by the use of a very bright white pigment next to it. But I can assure you there was not a blue pigment in sight in those areas!

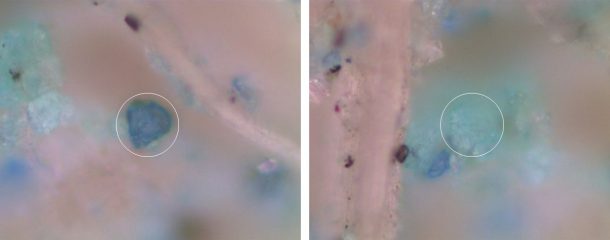

The other materials identified included lead white, vermilion, hematite, azurite, lapis lazuli, brochantite and shell gold. Of these, brochantite is a bit more unusual than the rest: it is a copper sulfate that is normally a bright blue-green to the naked eye, while it looks more like aquamarine under a high-magnification microscope.

In February 2017 we were also lucky to have the watercolour analysed using multispectral imaging equipment thanks to our access to the EU-funded MOLAB. Multispectral imaging is a wonderful technique that uses visible and infrared light to reveal what may lie under the surface of an object. In our case, it showed clearly the original pencil sketch, and what parts of the inscriptions were made with iron gall ink (they disappear when viewed with an infrared source) or with carbon based pencils or inks (they remain visible), as you can see in the video below.

We are so lucky that at least some evidence of the existence and appearance of this truly magnificent palace survives, if only in a small watercolour!