The legacy of Alfred Hoare Powell (1865 – 1960) and Louise Powell (1865 – 1956) testifies to the adaptability of manufacturing practices at Josiah Wedgwood & Sons in the early twentieth century. Their influence on the revival of hand-painting at Etruria is reflective of the values of the Arts and Crafts movement and shows their commitment to balancing Arts and Crafts values with the needs of large-scale machine production. This resulted in some remarkable work, which is highlighted here.

MARRIAGE AND PRODUCTION

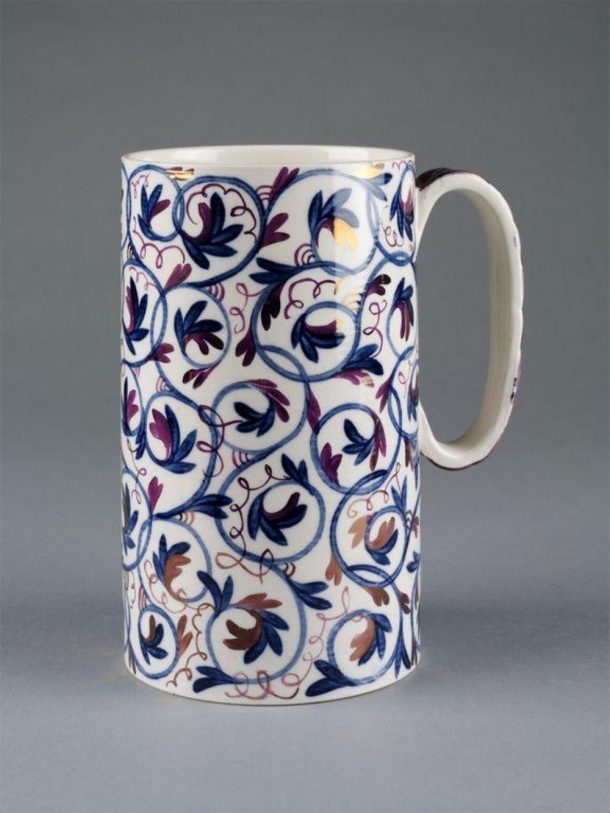

Alfred Powell, who trained as an architect, began designing and painting ceramics for Josiah Wedgwood & Sons in 1903. Three years later Alfred married Louise Lessore, the granddaughter of Émile Lessore, a famous Sèvres porcelain painter who came to work at Wedgwood in the 1860s. Louise was trained in calligraphy and illumination, and together they designed and decorated pottery, jointly signing and numbering many of the pieces they worked on together.

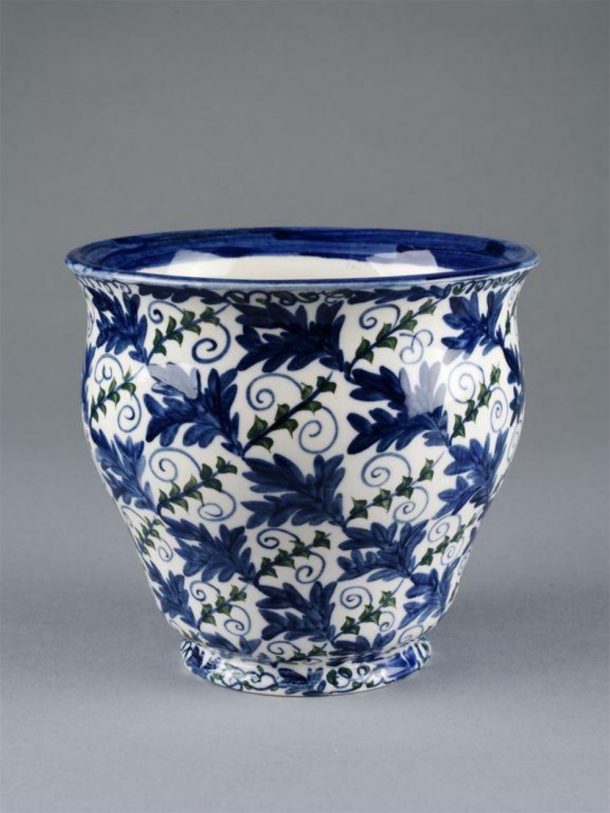

The difficulties we now face in distinguishing between their respective contributions is a direct result of their particularly collaborative practice. Their pieces display architectural elements, and often depict marine and animal subjects, while Louise’s calligraphic training is indicated through free-hand painting. Operating as a team, Alfred and Louise employed their unique skills in their decoration, production and teaching. At the turn of the twentieth century, women entering professions on their own behalf were often defined by the identity of their husband. However, Alfred’s acknowledgement of his wife’s talent and insistence that her name be recorded alongside his suggests a partnership of equals.

ARTS AND CRAFTS

The Arts and Crafts movement of the 19th century, led by figures such as William Morris, prompted a change in how much value British society placed upon the process of manufacture and design – instead of only valuing the end product. The Powells believed that a piece of art reflected the person who created it, and the conditions in which it was created. For them, workers should actively engage with the creative process of designing and manufacturing ceramics.

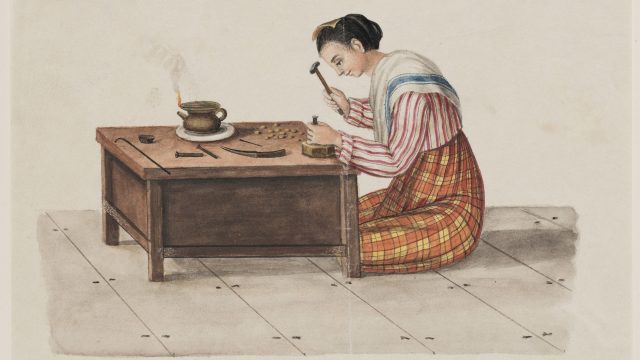

Edwardian Britain saw a social and economic emphasis on restraint and etiquette. Within this context, Alfred Powell condemned the dullness of the rigid mechanical print-and-tint process often used to create ceramics at the time. For Alfred, a mechanised process prohibited a worker from finding happiness in their labour, and he suggested to Frank Wedgwood (1867 – 1930), managing director of Wedgwood, that training in free-hand painting should be made available.

‘MAKE SUCH MACHINES OF THE MEN’

Josiah Wedgwood I’s desire to ‘make such Machines of the Men as cannot Err’ placed an overwhelming emphasis on consistency of production. As a forerunner of mass-production, Josiah I separated the process of creating ceramics into separate, defined tasks that were infinitely repeatable by specialists. By the time of the Powells’ involvement with Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, this desire for consistency had developed into factory processes far removed from the idea of ‘handcraft’. The Powells believed that designers should understand, and be involved with, the process of production for the objects they were designing.

Influenced by the work of Victorian critic John Ruskin – and his idea that the production of goods affected a nation’s social health – Alfred Powell believed strongly that finding happiness in work was essential to producing high-quality output. Furthermore, he valued greatly the skills of working people, and displayed a willingness to learn from them. The Powells spent time at the Wedgwood factory, observing and learning from workers. They were aware of the benefits of Wedgwood’s production line, but wanted to make principles of the Arts and Crafts movement compatible with factory production.

HAND-PAINTING REVIVAL

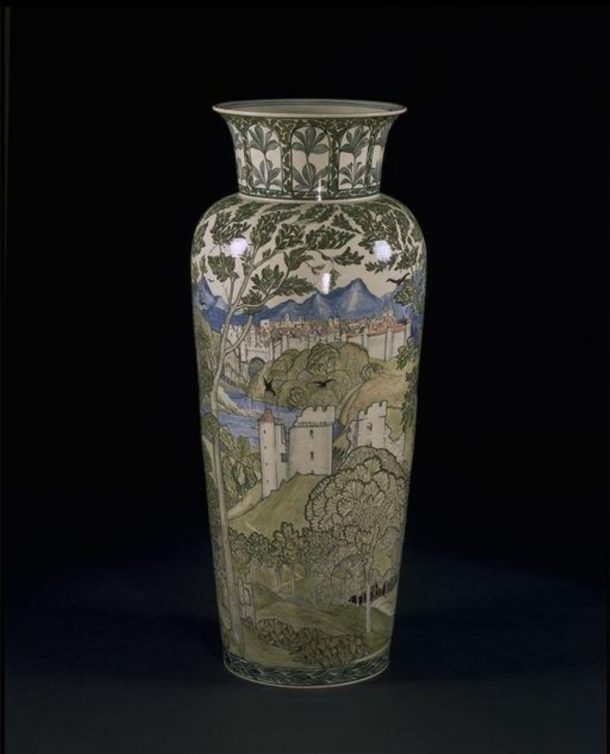

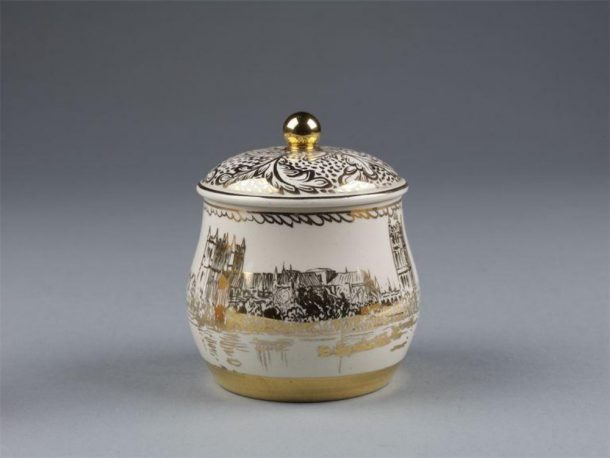

Importantly, Alfred and Louise Powell established a hand-craft department in 1926 at Wedgwood, under the control of Millicent Taplin (1902 – 1980), a painter and designer trained by Alfred. The department aimed to revive hand-painting for table- and ornamental-wares, designed for quantity production. Their commitment to helping workers find pride in their craft prompted the revival of hand painting at Etruria. Hand-painting was applied not just to artwares and specialist pieces, but also to large-scale production of items. The painters demonstrated great proficiency in learning the art of free-hand work and were more than capable of learning new styles routinely.

By the mid 1920s, more than 50 of the Powell’s designs had been put into production by Wedgwood. Furthermore, the creation of celebratory plates recognising the move of Wedgwood’s production to rural Barlaston in 1940 by the Powells demonstrates the harmony they envisioned, and achieved.

THE POWELLS’ LEGACY

The Powells’ achievement is noted clearly in a 1905 publication of The Saturday Review, in which Alfred Powell is praised for ‘lifting the cloud of dullness which made our work-people mere machines’. The revived importance of throwing and hand painting, which dominated design at Etruria during the 1920s and 30s, also shows their influence.

The commitment of the Powells to happiness in labour is remarkable and can be seen in the beauty and detail of their work. Their legacy continues to be defined by their skilled craftmanship and design, their collaborative nature in work and marriage, and – significantly – their belief in the right to creativity and happiness through work. In the present climate of mass strikes and undervalued workers, amid rising living costs, it appears that this sentiment is due another revival.