In 1787, Josiah Wedgwood began producing ceramic tokens with a protest symbol showing an enslaved man in chains. These jasper medallions were distributed for free – as one tool in the long campaign for British Parliament to abolish the slave trade. The medallion design was based on the seal of the Abolition Society was sculpted in 1787, probably by William Hackwood, Wedgwood’s best modeller.

This object has been the focus of a live-research project at the V&A Wedgwood Collection, during which we have taken another look at our collections to set the medallion in context and better understand Josiah Wedgwood’s role in the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade through his friendships and his products. Read on to discover some of these lesser-known stories and let us know your thoughts @vawedgwood

A critical friend

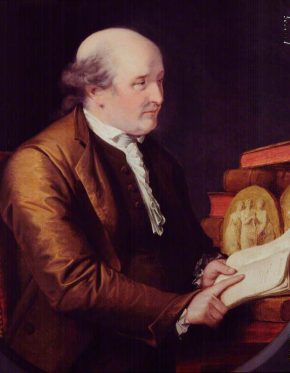

Thomas Bentley was Josiah Wedgwood’s friend and business partner, advising Wedgwood on matters from taste and fashion to commercial advancement, and influencing his views on the slave trade. As Nonconformist Protestants, or Rational Dissenters, Wedgwood and Bentley championed equality for groups including women and the working classes.

Bentley was based in Liverpool, a city at the heart of Britain’s slave trade. Over 5000 voyages set out between 1696 and 1807, transporting goods linked to the slave trade and enslaved people. Bentley’s vocal opposition to the slave trade was unpopular with fellow members of Liverpool’s merchant community but was supported by Wedgwood and a group of fellow scientists and industrialists known as the Lunar Society, who met each month on the night of the full moon to discuss the issues of the day.

Are we not Brethren?

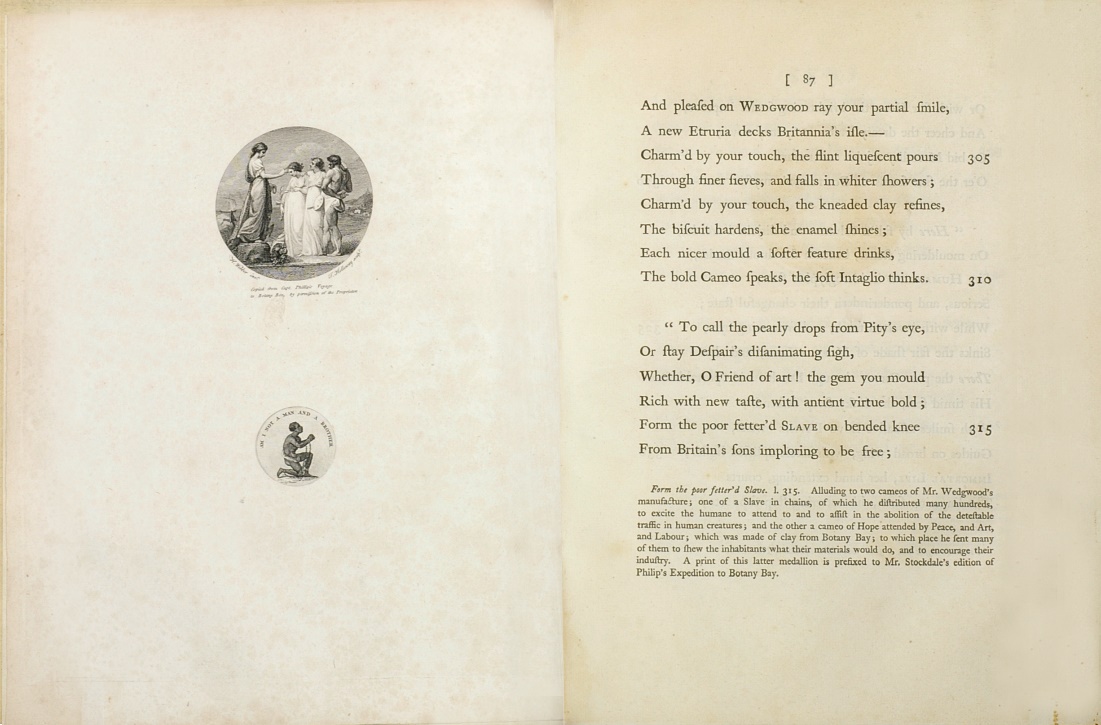

Erasmus Darwin, friend of Wedgwood and fellow member of the Lunar Society, was a gifted physician who published his politically progressive ideas in verse. Darwin’s popular poem The Botanic Garden, published in 1791, mentions Wedgwood’s medallion in its plea for an end to the slave trade.

Hear, Oh Britannia! potent Queen of isles,

On whom fair Art, and meek Religion smiles,

Now Afric’s coasts thy craftier sons invade,

And Theft and Murder take the garb of Trade!

—The Slave, in chains, on supplicating knee,

Spreads his wide arms, and lifts his eyes to Thee;

With hunger pale, with wounds and toil oppress’d,

‘Are we not Brethren?’ sorrow choaks the rest;

—Air! bear to heaven upon thy azure flood

Their innocent cries!–Earth! cover not their blood! (I.ii.421-430)

The poem is on display along with a portrait painted by friend of the Wedgwood family, George Stubbs.

Wearable allyship

Wedgwood’s abolition medallions soon became popular protest symbols. Abolitionists customised them into fashionable, wearable accessories such as buckles.

Thomas Clarkson, a member of the committee of the Abolition Society, wrote: ‘Some had them inlaid in gold on the lid of their snuff boxes. Of the ladies, several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair.’

Josiah Wedgwood was a great marketeer. By making these medallions in his unique jasper he was spreading awareness of his signature product to a wealthy audience, while contributing to a cause he believed in.

However, at the same time, there is a connection between Wedgwood and the prominent Birmingham metalware manufacturer, Matthew Boulton, who designed glittering cut-steel mounts used for some Wedgwood medallions. Capital from enslaved labour underpinned the financing of the renowned Boulton & Watt steam engine. From 1803 the company sold steam engines to the West Indies for the extraction of sugarcane juice – linking Wedgwood to the transatlantic slave trade.

Insatiable demand

These kinds of links, inconsistencies – hypocrisies – can be identified through several other objects in the collection. Josiah Wedgwood manufactured and distributed teapots and sugar bowls on a huge scale. The fashion for tea, coffee and chocolate, which taste bitter on their own, accelerated the demand for sugar and in turn for enslaved labour on sugar plantations in the West Indies. Only from the 1840s onwards did beet sugar, which was produced without enslaved labour, play a noticeable role in the British sugar market.

In effect – while abstaining from sugar and campaigning for the abolition of the slave trade – Wedgwood was indirectly profiting from it through his product range.

A bitter-sweet connection

The design on this tea canister shows a black child waiting on a couple taking tea. This was a popular scene that Wedgwood was able to reproduce in partnership with Liverpool-based printers Sadler & Green. Black children were brought to Britain as domestic servants, perceived at the time as ‘fashionable accessories’ who, unlike their white counterparts, were often unpaid and were tied to their employers.

Invisibly intertwined

Josiah Wedgwood took inspiration from ancient vases and reliefs being discovered in Greece and Italy, while at the same time, many country house owners were renovating or rebuilding their houses in the latest neo-classical style. Wedgwood’s wares in elegant black basalt or pastel-coloured jasper complemented these interiors perfectly and were purchased as features for mantelpieces and alcoves.

The wealth of many British country house owners came from profits generated by enslaved labour, making Wedgwood – as an entrepreneur catering for the luxury market – an indirect beneficiary.

Enslaver turned abolitionist

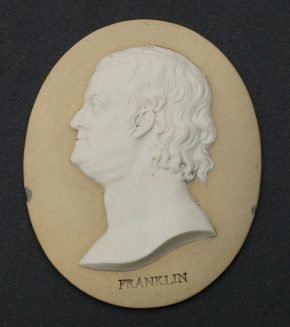

Wedgwood did, however, ensure that his medallions reached the right people, including future Founding Father of the United States, Benjamin Franklin. Resident for many years in England before the outbreak of the American War of Independence, Franklin mixed in Bentley and Wedgwood’s progressive scientific, religious and political circles.

Though he would become a prominent supporter of the abolition of the slave trade in later life, Franklin held enslaved people in his household from the 1730s; Peter and Jemima, two of these enslaved people, travelled with Franklin to England. In 1788 Wedgwood sent Franklin a batch of jasper abolition medallions to give to his friends in America, the response from Franklin read: ‘I am persuaded [the medallion] may have an Effect equal to that of the best written Pamphlet in procuring favour to those oppressed people.’

A second generation of campaigners

Here you see Josiah Wedgwood with his wife Sarah and their children, who continued the fight for abolition.

In 1807 an Act of Parliament was passed that ended the British trade in enslaved Africans –slavery itself was not formally outlawed in most British territories until 1834.

Josiah Wedgwood II, known as Jos, is pictured on horseback in the centre of this portrait. He was elected Stoke-on-Trent’s first MP, the result of the 70 years of campaigning for new industrial areas to have representatives in Parliament. Jos used his election to call for the ‘immediate abolition of slavery’.

‘The cement of the anti-slavery movement’

In 1825 Sarah Wedgwood, Josiah Wedgwood’s daughter, formed with other notable women the Birmingham Ladies’ Society for anti-slavery. It raised funds, recruited support and planned sugar boycotts. Three years later, Sarah founded the North Staffordshire branch.

Women’s political groups such as these created new spaces for women to debate and campaign for their political beliefs, a right that had often been forbidden them on the grounds of their sex. While women were allowed to become members and to give financial contribution to the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, prominent abolitionist, MP William Wilberforce denied them leadership roles, believing debate and campaigning to be ‘unsuited to female character’. The more radical female-led efforts were later seen as pivotal to the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act.

The society also produced protest materials such as this silk reticule which aimed to promote empathy in those who saw it. To our eyes now, this object feels full of contradictions and the power dynamics of white supremacy. Its luxurious material and function as a wearable fashion accessory is at odds with the image of the distressed black woman.

For more information on this project and to share your thoughts on where we go from here, follow us @vawedgwood

I Am a Man and a Brother is a display and trail at the V&A Wedgwood Collection in Barlaston, Stoke-on-Trent and is free to visit Wednesday – Sunday, 10am-5pm until early 2022.

This programme has been developed in partnership with Grace Barrett, founder of anti-racism teacher training programme I AM ALLY and Georgia Haseldine, V&A Research Institute Public Engagement Fellow, made possible with Art Fund support, and support from World of Wedgwood, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the British Ceramics Biennial.