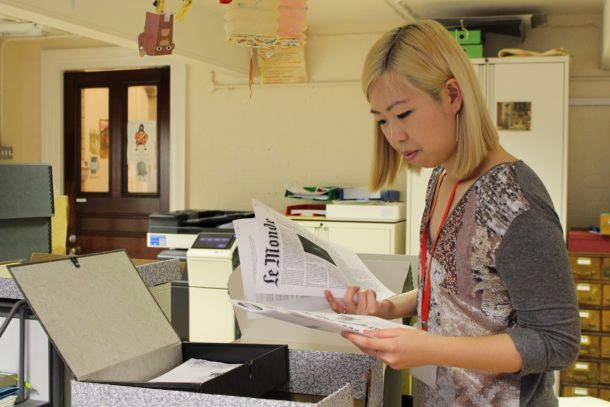

Corrie Tan, volunteer in the Department of Theatre and Performance, describes her experience working with Theatre and Performance Collections.

I’m on tiptoes atop a yellow ladder I will eventually christen Eric (after Eric Morecambe, but I don’t know that yet), reaching for a grey archive box sandwiched in-between two others, stacked high on a tall metal frame. There is a wig in here that needs checking, and two of my colleagues are looking up at me. They are also looking slightly concerned.

“You’re tall! Well, above average height. You’re going to be asked to help reach for a lot of things,” is one of the first things I am told when I begin my volunteer placement at Blythe House.

So here I am, reaching.

“Are you alright?” one of my colleagues calls out, several feet below me. I kick myself internally for wearing a dress today, which I surreptitiously try to hold down with one hand as I ease out the box with the other. But it’s a success. I don’t flash anyone, the wig of blonde curls is in one piece, and is checked off a long list of others, from a well-coiffed Japanese Noh wig under a bell jar to Laurence Olivier’s rather suspect Othello hairpiece from 1965, when the actor performed in blackface.

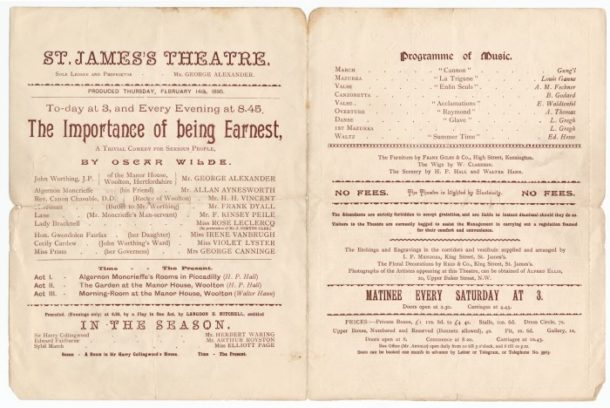

Over the summer, I’ve been volunteering with the V&A’s Theatre and Performance department at Blythe House, where the national theatre collection is stored. As a complete newbie to the museum industry, I’ve had to learn most of my duties from scratch. My previous life as a theatre journalist in Singapore had not quite prepared me for the completely different cultural context of the UK, and the past few months have been an excellent crash course in the country’s incredibly rich theatre ecology. My introduction to Blythe House was as a chaperone for a small group touring the archives and stores as part of the Hammersmith & Fulham Festival in June. Ramona Riedzewski, head of collections management, was leading the tour. She took out several items for the visitors to see: a pair of dainty white gloves worn by Ginger Rogers; one of the heavily lined prompt books for the West End’s longest-running show, The Mousetrap; the programme and cast list for the very first performance of The Importance of Being Earnest by Oscar Wilde. How incredible, I thought, that the archivists here can reach out and hold history, turn it over in their palms. I thought of Fred and Ginger clack-clacking across a shiny floor, her dress spinning up over her knees; of the uneven amateur production of The Mousetrap I’d seen in Singapore in a fit of nostalgia over all the Agatha Christie novels I’d devoured as a teenager; of the brilliant all-male take on Earnest by the Singaporean theatre group Wild Rice, a cheekily subversive performance in a country where homosexuality is still illegal, even if the law against it (inherited from British colonial rule) is not enforced. All these objects, play scripts, programmes and costumes, nestled in archive boxes or hung on rails, each with a different story to tell, or a reminder of a story now forgotten.

St. James’s Theatre (London, England)

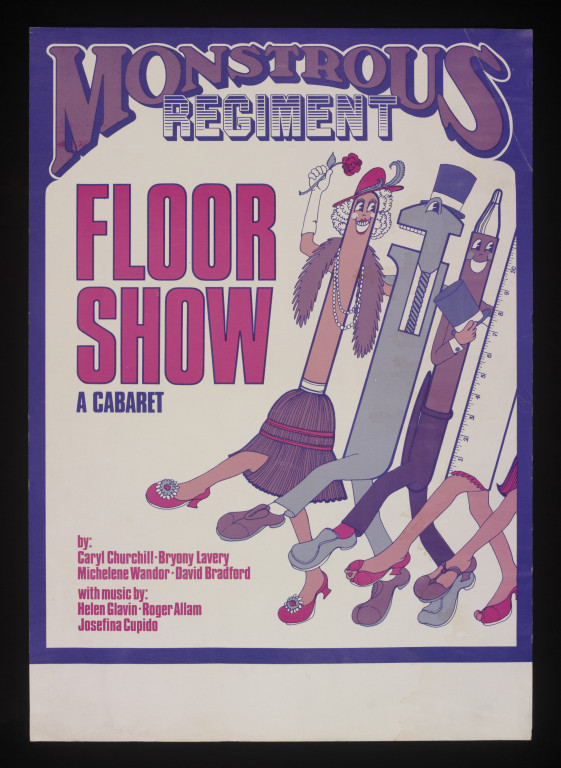

One of my first projects was to put together a digital database of touring productions by the women’s collective Monstrous Regiment, active throughout the 1970s to 1990s. It was always a thrill to see a glimpse of what might have been Caryl Churchill’s handwriting, or Bryony Lavery’s. I pored over decades of faded press clippings, production management notes, and polarised theatre reviews often more revealing of the reviewer than the reviewed – altogether they were an intimate look at the struggles and triumphs of a theatre group that defied categorisation and how they evolved with the times. Over the years, publicity materials became slicker and more beautifully designed, they eventually hired administrators who would become beloved members of the company, from the records of their tour bookings I gleaned the thrill of going international. With every new production I was eager to find out: what issues would they take on next? Violence, sex, politics, gender, productions that bent space and time – nothing was out of reach. When I completed the final entry, I felt as though I was saying goodbye to a newfound but well-loved friend. Then I helped rehouse photographs and correspondence from the King’s Head Theatre and Talawa Theatre Company archives, puzzling over where various bits and pieces should be stored for proper integration. I was also given the responsibility of labelling all the ladders and step-stools scattered throughout the archive; the trolleys had already been labelled and named after prominent musicians (from David Bowie to Adele), so the ladders were to be named after British comedians. Monty for the Pythons, Eric & Ernie – and the very tallest ladder I could find was dubbed Miranda.

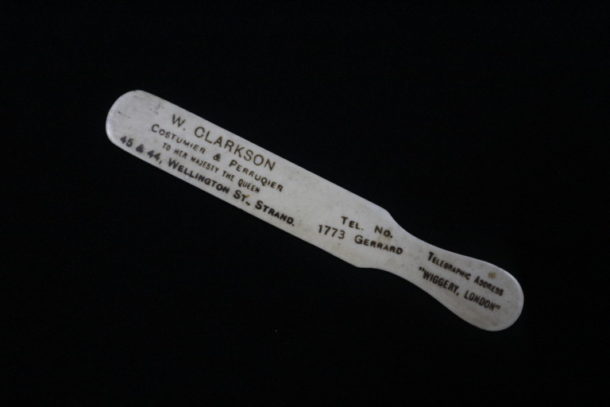

There isn’t a centralised theatre archive in Singapore, whose contemporary theatre scene is a comparatively nascent one. How meticulous and organised each theatre archive is often depends on the leadership of each theatre company. Documenting and archiving theatre and performance isn’t quite a national priority yet, although in recent years there’s been a more concerted push to do so, with smaller repositories and well-ordered company archives becoming available and accessible to the public. I’d always wondered – how does one conserve and preserve theatre, the art form that is contingent on its live-ness and ephemerality? I’m still not sure if we can, even if the V&A now does its best to film a variety of theatre productions for its film archive. But someone going through the texts and objects in the archive might be able to piece together the preoccupations and passions of a nation, drawing from the plays that captured the imagination and the thousands of others quickly forgotten. Ramona once showed me a small collar stay from the early 20th century, sent to the museum by a member of the public. The item – which doubled as a calling card for a ‘costumier and perruqier [sic] to her Majesty the Queen’ – wasn’t particularly rare or valuable, but she felt it was interesting, and promptly filed a report that would allow the V&A to acquire it through the proper channels. It reminds me that there’s never just one official narrative to a country’s history, but a chorus of overlapping and intertwining voices, each and every one accounted for, no matter how small.

To find out more about Theatre and Performance Collections visit Search the Collections and Search the Archives. The database of Monstrous Regiment Theatre Company performances is available through AusStage.