Krupa Desai is one of 12 participants who took part in Field Notes, a summer school organised by the V&A in collaboration with the environmental charity Sylva Foundation. Field Notes was conceived as a platform for creative practitioners with an interest in wood. Under the mentoring of foresters, academics, designers, and museum professionals, the participants developed and applied woodworking skills in a managed forest setting. While each of their projects was unique in expression, all participants developed a holistic approach to wood. Krupa Desai’s project was a very personal and affective investigation into motherhood, belonging and memory, her approach being one that explores the relationship between maker and material as a mutual dynamic.

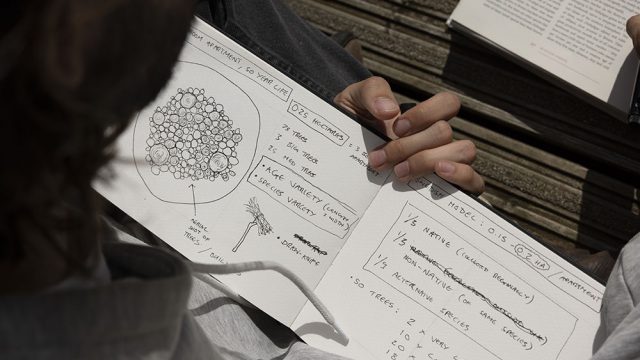

Documentation was important to Krupa’s process. She recorded her surroundings – natural and social – with photographs and sound recordings, and by hand-working a piece of ash wood. Some of Krupa’s photographs are in the V&A’s Furniture Gallery until October 2023, together with her hand-carved tray in ash, and her narration, in which she describes the relationship that she developed with the wood used for the tray. Her audio essay ‘reflects on the process of making the wooden object, offering an intimate contemplative lens as a way of “witnessing” the transitions that drive the natural world within and around us.’ Here is the transcript.

Being a Witness – My story of making the tray in ash wood

How did I arrive here?

While growing up, I remember some of the most beautiful pillow covers at home were made from my mother’s old sarees. The cleaning napkins used in the kitchen were remade from my baby blankets. Sometimes one of them would have a little crayon scribble that is persistent despite several washes. At other times, using an upcycled object would suddenly trigger a beautiful memory of my grandma wearing that same piece of cloth and laughing with us. Thinking of those, I feel intrigued by the manner in which objects seamlessly become a part of our collective lives – our histories and present. Aren’t they curious beings, permeating our emotions, enlivening our memories and crafting our identities? And yet, we use myriad objects – books, clothes, furniture, on an everyday basis, only to eliminate them without much thought. There is an increasing recognition that many of the present global challenges are a result of alienating consumption patterns created over the last couple of centuries. In our preoccupation to consume and replace, we suffer from a constant disengagement with objects that make us.

Being a witness would mean being engaged, involved and interested in KNOWING how these objects come to us, in how we live with them while they integrate into our lives, and how we bid farewell to them as they take on new lives. In many ways, being a witness is an intense act of accompanying, as a friend, as a companion, and as a giver and receiver of care and comfort.

‘Witnessing’ is allowing ourselves to pause, and [talks to] how objects live on around us in traces of their old selves, humbly acknowledging the universal truth that everything that comes to us has a past and a future. That existence is cyclical, we all come and go, only to appear again in another form.

It was this idea of witnessing that I wanted to explore when I joined the summer school. I began wondering how I could truly engage with an everyday object, how could I be an engaged witness in space of making and learning, and if this modality of engaged witnessing could transform my relationship with wooden objects in my life, and woodlands in general.

How does a tree become timber – a resource to be worked with?

I met the wooden tray you see here, as a trunk of an ash tree drying itself with the wind. Fraxinus excelsior or Ash, as is commonly known, is a hardwood in Europe, known for its strength and resilience. I remember that the environment where this ash was kept had a certain air of un-delicacy about it. And yet, I was enamoured by the felt heaviness of it. I had an immediate sense of how formidable it felt, something that was hard to shake off, something that was aware of its weight on the ground and gloriously owned it. The indelicate handling of it did not make it a victim but defined its existence by a display of its formidable strength.

My next encounter with this ash was at the sawmill. It was ready to combat the mechanical mercilessness of the saw, meeting the deafening grill of the saw machine with the cultivated poise of someone ready for a rite of passage, knowing that this is the change they are ready to embrace. It was a bitter-sweet moment that roused conflicting emotions – a deep sense of pain on seeing the ash tree lose its old form as it was slashed by the mill, accompanied by a sense of wonder at the generosity of possibilities offered by the wood in its new form as a resource.

As the saw slit the ash trunk layer by layer, the tree revealed beautiful prints of its ventricular structure. Traces of old wounds resurfaced as knots as if the trunk was ready to shed its formidable demeanour to reveal a more delicate inner being. I couldn’t help but be shaken by the power of its delicacy, much like how a conscious display of vulnerability has the potency to invoke something very fragile in the gut of its witnesses.

This particular piece of wood, which you now see as a tray, struck me as an image of a womb with its intricate whirling of lines converging into a circular form, dark at the centre as if holding something heavy, lightening out as it moved away from the central knot. The womb’s symbolism of new life, continuing growth and a fragility that was rock solid at its core felt important to me even though I learnt that most furniture makers would avoid working with knots for the sheer unpredictability of how it will change their form over the years. I decided to stay with this piece of wood as I knew this was the one that I wanted to integrate into my life.

I find it particularly fascinating that the knot here carries a memory of its older self as a tree. When a tree loses its branch, there may not be a visible sign on the outside, but on the inside, a mark remains. This mark is a reminder of the many lives sustained by the tree, of the many scars that healed, of the many bumps that smoothened over time. It carried with it the existence of a tree I had not known until the day we met. Aren’t we all a little bit like that? No first meeting is an authentic first. Nothing new is truly new. A memory of what we have lived – physical, psychological, sensorial, stays within us and makes us who we are in the present moment. How to meet then, valuing the present moment of engagement, while being sensorially cognisant of the past that each of us brings to this present? How to acknowledge the tree-ness of timber, while interacting with the possibilities of using the timber-ness of the tree, utilising its resource-ness for what it can offer?

Working intimately with the wood

I decided to hand-carve the dip in the tray with a set of chisels. Carving felt like peeling off the skin, layer by layer. A range of colours appeared gently with layers of the wood peeling away – red, brown, and green with a tinge of purple, triggering a vivid image of veins seen on a human wrist. Each shade was accompanied by a subtle emotion. Sometimes I was astonished at my ability to keep digging in, chipping away layer by layer despite witnessing the force of life resisting my efforts. Was I being cruel? Should I be feeling guilty for all the wood I have mindlessly used and discarded without a second thought, thus far in life? Is this stubborn cruelty to keep altering the wood form, inherent in the race for survival embodied by the human species? Is there a way to resist and alter nature in a manner that is empathetic and kind?

I cut myself twice during the carving process. Each time, it was a result of my desire to rush and finish. Once I tried to chip away a small fibre from an unclamped piece of wood. Another time, I was trying to get a ‘neat’ finish and rushed through the edge I was trying to perfect. Both times, the piece of wood resisted my attempts and pushed the chisel back into my finger. I learnt that the inner resistance of the wood had to be met gently, acknowledging that using extra force could be counter-productive. I needed to respect the inner structure of the wood, its resistance to being moulded against its grain, to be chiselled away as per my sole will.

As much as I wanted it to be a gentle meditative process that I could romanticise about, it was quite tiring, generating immense fatigue. At other times, I was amazed by the sense of care and nurture welling up within me in response to this small piece of wood. My sustained attention and attunement to every single aspect of this piece intensified my investment in the wood, the ash tree and the forest where it must have grown.