The last post about the 1880s Forth Bridge’s living model focused on confidence in engineering innovation. This time, the living model will tell a story about the connections between Scotland and Japan, revealing how engineering became a rich field for technology transfer between West and East in the late nineteenth century.

A central position?

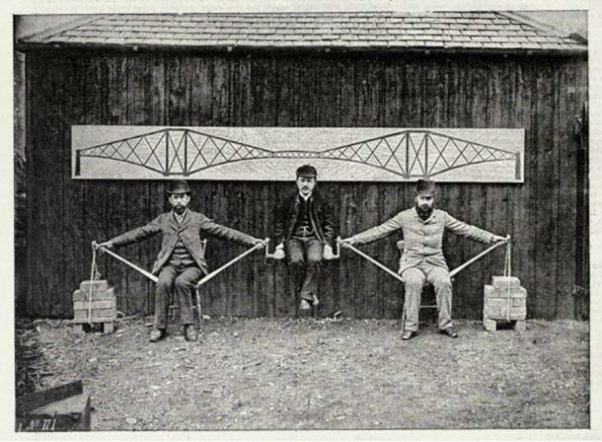

The ‘central load’ in the photograph above is provided by Kaichi Watanabe (1858 – 1932), a Japanese engineer who worked on the Forth Bridge construction. Watanabe was placed strategically between engineers Andrew Stevenson Biggart (left) and Frederick Eastment Cooper (right). The model showed not only how the cantilever forces operate, but also how West and East were themselves ‘building bridges’ at the end of the nineteenth century. In fact, it is commonly said that Watanabe was given the central position to acknowledge the Eastern origins of the cantilever principle.

A two-way bridge between Scotland and Japan

The nineteenth century was a period of great change in Japan. Although tradition was a strong part of the country’s identity, Japan sought Western expertise in science and engineering to industrialise. At the same time, Scotland was also experiencing an intense period of development. That context brought Scottish engineer Henry Dyer to Tokyo’s Imperial College of Engineering. He introduced engineering courses taught in English, following Western programmes and teaching methods. Dyer, himself a graduate of Glasgow University, would be responsible for the instruction of many Japanese engineers. He later influenced the journey of some of them to Glasgow to complete their studies – one of them was Watanabe.

Watanabe studied engineering in Tokyo under Dyer and moved to Glasgow University, where he graduated in 1887 with degrees in Science and Civil Engineering. He worked on the Forth Bridge construction and in 1888 returned to Japan, where he participated in several railway projects and steered many engineering companies. Watanabe was a main figure in Japan’s early technological and engineering development in the 19th century.

Watanabe’s presence in Scotland was still fruitful after more than a century: his role in the construction reinforced the listing of Forth Bridge under the ‘international influence’ criterion for its nomination for inclusion in UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The bridge has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2015.

Was it Really ‘a compliment to the East’?

Let’s look at the living model again. Did this photograph really reflect the intention to ‘build bridges’ with the East, or did it set East and West apart by embodying their differences?

The records of Benjamin Baker’s lecture on the Forth Bridge, held in 1887 at the Royal Institution in London, did not mention Watanabe. And although Baker insisted that cantilever principles had already long been used in the East, his statements did not really acknowledge Eastern technological proficiency, on the contrary, he said: ‘even savages’ had used cantilever principles in primitive bridges. In fact, an alternative interpretation of the model’s set-up could underline the impression the viewer gathers from the image, that the two Western engineers are ‘carrying’ their Japanese colleague.

Most accounts, like Baker’s lecture, promote the inaccurate idea that the West was the ‘cradle of technology’ and suggest Western cultural and technological supremacy across the board. While the influence of the West is unquestionable, the opposite story is less known and needs further investigation: Japanese engineers had a Westernised education in Japan, but what kind of technological knowledge did they bring to Glasgow? How did Watanabe influence the construction project?

The Forth Bridge living model embodies different layers of technological transfer between West and East in the late nineteenth century.

Building models to build bridges

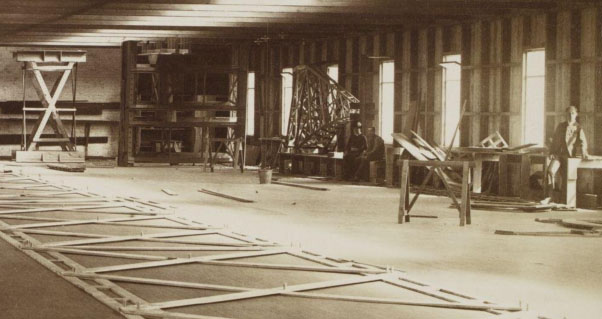

The human living model is probably the most famous Forth Bridge model ever created, but more conventional ones exist. The proof for this lies in the image below, a detail of a 1885 photograph from the V&A’s Prints, Drawings and Paintings collection, currently on display at V&A Dundee. It depicts a human-size maquette of a part of the Forth Bridge, next to the windows. Lofting, a drawing technique used in shipbuilding and bridge engineering to convert technical drawings to full size templates, was taking place on the floor. Possibly the model was used as a working tool to guide the lofting process.

The human model was a presentation model. It ‘built bridges’ by creating credibility within the public and embodying technology transfer between West and East. But it should not erase the more prosaic, functional models that effectively ‘built the bridge’, such as the one below. After all, models are real tools for thinking, designing and problem-solving.

Want to experience the living model for yourself?

The photograph of the 1885 living model can be seen until 5 March 2022 at the Building Centre in London, in the exhibition ‘Shaping Space – Architectural Models Revealed’, a collaboration between the V&A and the Building Centre.

Will you fall? A free workshop re-enacting the living model will take place on 12 February 2022 at the Building Centre, generously supported by Webb and Yates Engineers. Find out more and register for the workshop.