Written by Gary Haines, Archivist at the V&A Museum of Childhood

When visiting the Fashioned from Nature exhibition, it struck me how, in many ways, I was following in the footsteps of the first visitors to the V&A Museum of Childhood in 1872. These visitors would not be viewing the range of toys, clothes, furniture and other objects, which reflect the diverse nature of childhood, that are currently on display in the museum. Instead, they would be viewing animal and food products alongside artwork. The Animal Collection includes some of the animal products now on display in Fashioned from Nature.

The 19th century saw greater opportunities for middle- and working-class people to learn about natural history and the countryside which surrounded the increasingly industrialised cities. This was encouraged, particularly as an aim for the working classes, as it fitted the idea of ‘rational recreation’. This movement was led by middle-class reformers who believed that leisure activities should be controlled and educational. Leisure time should not be used for purely self-indulgent pleasure.

The ideal place to put ‘rational recreation’ into action was in the borough of Bethnal Green. In the Tudor era, Bethnal Green was a popular London suburb for the gentry. It was the fashionable place to live with lots of greenery and farmland.

Samuel Pepys was an admirer of the area and in June 1663 made a visit to his friend Sir William Ryder, located at Bethnall House in Bethnal Green, and described in his diary Ryder’s garden with a great quantity of quality strawberries. It was here that Pepys would deposit his diary for safe-keeping during the Great Fire of London in 1666.

We can see the rural aspect of Bethnal Green highlighted here.

Of course, this all changed due to industrialisation and urbanisation and by 1847 it was recorded that 82,000 people now lived in Bethnal Green. The rural traditions of Bethnal Green, however, carried on and it was found that there were 408 cows and heifers in milk, kept by 37 people, in 1874. Presumably these were used to supply milk to the ever-growing population. They of course also contributed to the poor housing and sanitary conditions in the area. There had been a Cholera outbreak in 1832.

The Animal and Food collections had their origins in the Great Exhibition, or to give it its full name, the ‘Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations of 1851’. They were deemed to be no longer needed at South Kensington so the decision was made to move them across to the Bethnal Green Branch of the South Kensington Museum, as the V&A Museum of Childhood was originally called. Science and education were the core aims of bringing the collection to Bethnal Green, so it could reach out and educate a new audience. The Food Collection was arranged by ‘chemical composition’ clearly highlighting its scientific, educational aims.

The Animal Products collection was displayed in frames, glass cases and glass jars. We can catch a glimpse of this arrangement in this illustration of visitors to the Museum on the day of opening in 1872.

The Food and Animal Product collections were joined by another scientific collection three years later, the Waste Products collection. This display included three jars of human faeces to show the process of sewage management: a life and death industry, quite literally in Bethnal Green. The collection showed a diversity of items, all of which were labelled in detail giving names, potential uses and their value. This was the collection of P. L. Simmonds who had also contributed greatly to the Animal Products Collection.

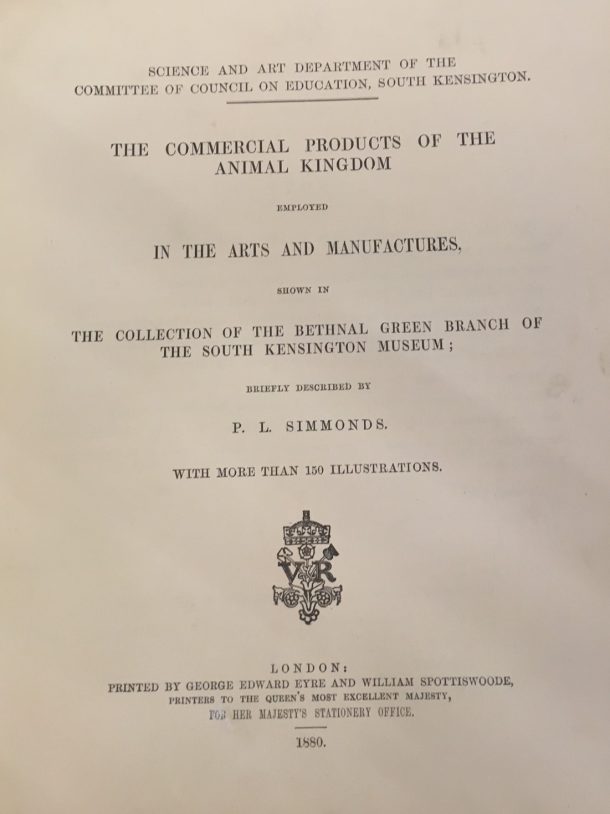

In 1880 a large format guide of the Animal Products Collection was produced and written by Simmonds. It is through this that we gain a clearer knowledge of the Animal Products Collection and its popularity, as stated in the introduction:

The brief descriptive framed labels of the Animals Product Collection in the Bethnal Green Branch Museum, prepared by Mr P. L. Simmonds, are found to be much studied, and many have frequently been copied by visitors. Repeated applications for sets have also been made for public and private schools, technological museums, and scientific establishments at home and abroad, which it has been found impossible to supply. To meet this demand for popular scientific information the Lords of the Committee of Council on Education have directed these labels to be reprinted, in a collected and cheap form, with merely an occasional alteration of figures, so as to bring the statistics furnished down to the most recent period, and the additions of some woodcuts. It must be clearly understood that these are no more than terse digests or summary descriptions of the principal products. The edible substances derived from animals are not included, as these are classed in another section of the Museum – the Food Collection.

January, 1880.

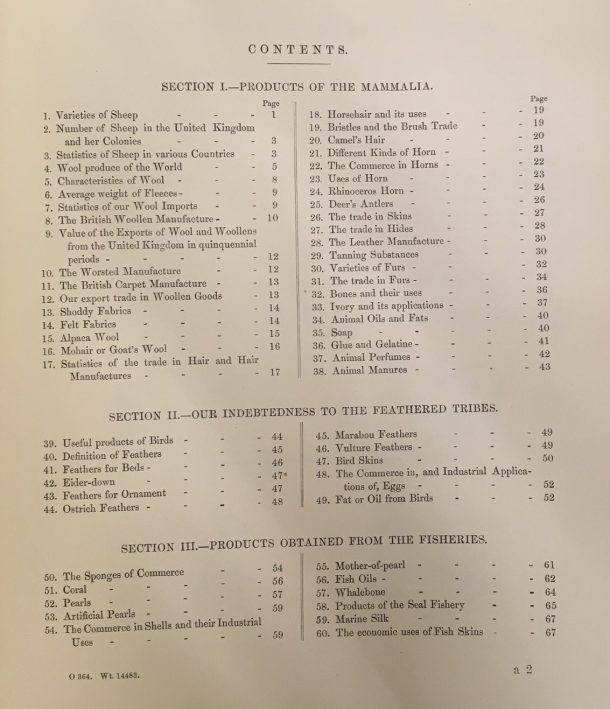

The section headings of this work tell us all about the variety of Animal Products that were on display:

Section I: Products of the Mammalia

Section II: Our Indebtedness to the Feathered Tribes

Section III: Products obtained from the Fisheries

Section IV: The Commercial Products and Uses of Insects

Section V: Reptilia

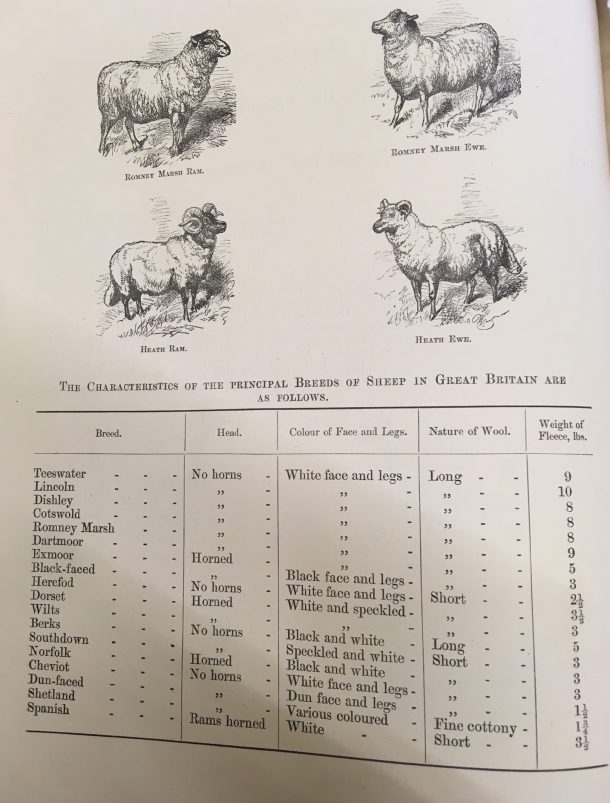

Within this beautifully illustrated guide can be discovered a range of fascinating facts. The number of sheep in Great Britain at this time: 28,406,206. Weight of goat’s hair imported in 1874 into the United Kingdom: 8,013,706 tons.

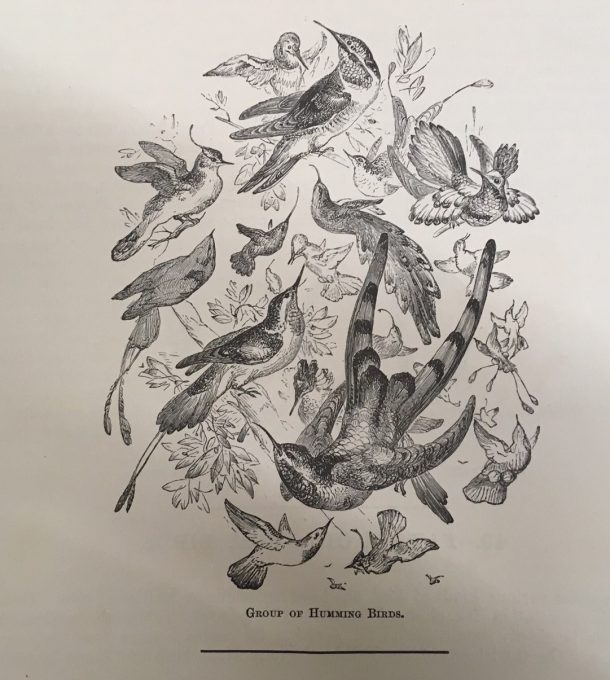

Other statistics remind us of our impact on nature: 762,772 seal skins were imported in 1878. The catalogue also states: ‘The taste and luxury of late years have drawn very largely upon feathers for the purposes of ornament and dress.’ Imports of feathers for ornamentation were worth £1,002,902 in 1878 (over £109,000,000 in today’s terms) and weighed a total of 264,799 Ibs.

It was not just feathers that were used in ornamentation as noted by Simmonds: ‘The importation of bird-skins for the decoration of ladies hats, head-dresses, etc, has now become an important trade. Over a million of small foreign bird skins of brilliant plumage are imported here annually … In 1872 the skins of 3,000 birds of paradise were shipped from the port of Dobbo in the Abu islands.’

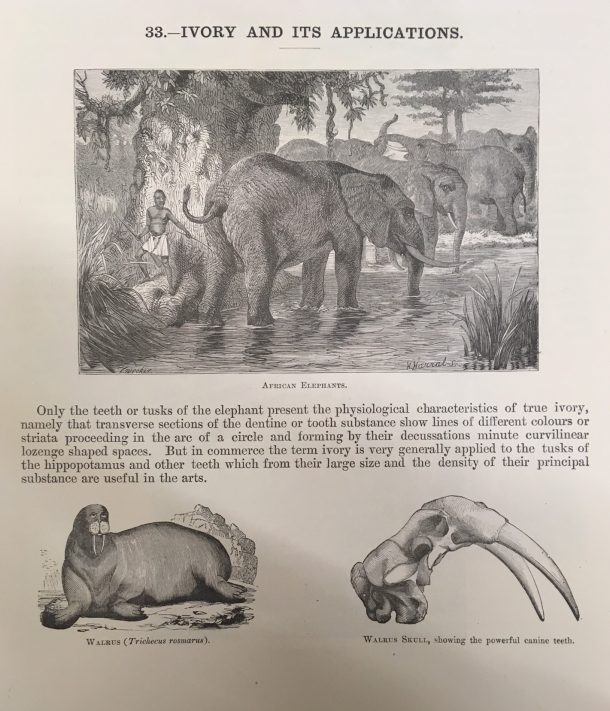

Ivory is also noted as being of commercial value: ‘The supply of ivory does not seem at all to diminish, but rather increases.’ It is estimated that approximately 26,000 elephants were killed in the last five years to supply 692 tons of ivory to the import market. An obscene statistic.

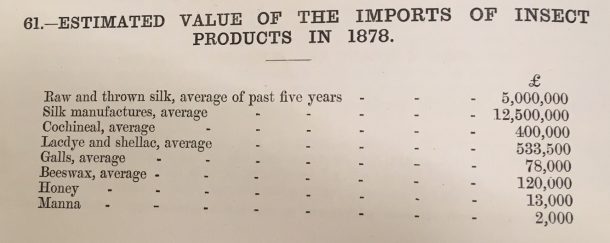

Large animals were not the only animals whose products were used and displayed. Insects also played a valuable role as a table in the guide shows:

An article in All the Year Round from 1872 gives us a valuable first-hand experience of visiting the Animal Collection. It describes a visit to the Bethnal Green Museum in July 1872 and was probably written by Charles Culliford Boz Dickens, the son of Charles Dickens, who was editor of All The Year Round at this time. It does somewhat illustrate that not everyone was interested in the Animal Products Collection . . .

Neither is it necessary to chronicle the acute boredom and mental prostration which overcame most of us when we fell a prey to the Food Collection (although Mr. Cole does tell us it is one of the most popular divisions of the South Kensington Museum), or worse still, when we were claimed for its own by the Animal Products Collection, which is “intended to illustrate the various applications of animal substances to industrial purposes.” It may be merely recorded that we took no interest in the quantity of water contained in rye, that albumen and gluten did not come home to our feelings, and that for the most part we looked with incredulity, if not with contempt, on the glass phials and cubes supposed to represent the chemical components of the human body. Nor did an exhibition of mushroom powder, of dried mushrooms, and of a bottle of mushroom ketchup, at all raise our spirits. Indeed, in this department all that we seemed curious about was the case containing the analyses of various kinds of liquors, and as that reminded us that the human body requires periodical refreshment, we generally withdrew after a brief examination of this part of the show.

It would be wrong to assume that those who lived in Bethnal Green, a place of overcrowding and poor sanitation which is often dismissed as ‘dirty’ by historians (and by association implying the people were dirty and uneducated), did not have time to appreciate art and the beauty of life and, as hinted in the above, would rather go to the pub.

In 1888 Queen Victoria loaned the Bethnal Green Museum a selection of the Jubilee Presents she had acquired.

In this year the numbers visiting the Bethnal Green Museum exceeded those of the main V&A: over 900,000 visitors.

Many visitors were educated and intrigued by the Animal Products Collection during its display in Bethnal Green. The publication of a guide in 1880, which was the result of sheer demand, is evidence of its popularity. The Animal Products Collection was available to view from 1872 until the late 1920s when the reorganisation of the Museum began under the guidance of head curator Arthur Sabin. By this point much of the collection was marked as ‘decayed’ in the register. However, it was still a draw for visitors. Certainly, one Archibald Hattemore was fascinated by the Animal Products Collection, as he painted this eye-catching picture in 1928.

Perhaps those of us that visit museums and galleries are still undergoing what could be termed ‘rational recreation’. Being an east ender perhaps I am. But I call it joy. There is joy in viewing a wreath of fish scales and beads made around the 1870s, or a group of flowers modelled in wax by John Haynes Mintorn in 1875. The delicacy of the object is beauty in itself. It is that extraordinary feeling you feel when you see an object of beauty for the first time in Fashioned from Nature; you admire its lines and curves, its craftsmanship and wonder about who made it and who wore it. This feeling is one that we share with the people of Bethnal Green. They would also have experienced these emotions when visiting the Bethnal Green Branch Museum of the South Kensington Museum in 1872 and seeing the diversity and beauty of nature and the crafts and skills of people from faraway lands which was in the Animal Products Collection. They could themselves be said to have been ‘Fashioned from Nature’, as we are today.

The Guide to the Animal Products collection and Queen Victoria’s Loan as well as the Registers of the Animal Products Collection can be viewed via appointment to the archives of the V&A Museum of Childhood. Please contact Gary for further details, g.haines@vam.ac.uk.

The next post will give you the chance to put your knowledge of the history of fashion to the test.