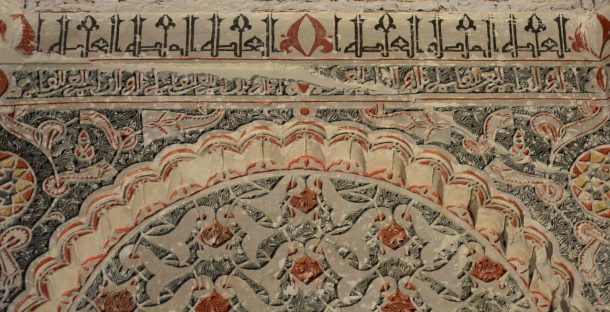

Epigraphy is the word we use for the study of inscriptions. Two of the ceilings from the Torrijos palace were originally associated with a plaster frieze containing legible Arabic inscriptions. The sections of original plaster frieze conserved in the V&A show one single phrase that was repeated all around the ceiling-crowned space. This has been read (by José Miguel Puerta Vílchez and Péter Nagy) as wa tashrabūna min al-surūr. This could be translated as “You drink out of happiness” or “Happiness makes you drink”. The verb in this sentence is in the plural and it is therefore addressed to several people. The phrase seems to establish a link between happiness and drink, implying that it is the happiness felt that encourages the guests to drink. This might refer to the activities of feasting and hospitality that likely took place beneath these ceilings. Indeed, contemporary sources describe informal receptions where spiced wine was enjoyed by the patron and his intimate circle.

The use of ornamental Arabic characters in this palace is part of a long Castilian tradition. The calligraphy and ornamentation are in keeping with the Toledan style, in particular the characteristic interlacing of the shaft of the letter ‘m’ (the mim) and the decorative background formed of palmettes and arabesques.

However, the content expressed appears to be completely new. This formula seems to refer to Bacchic poetry, which originally consisted of verses dedicated to the god Bacchus, who invited the gods and men to enjoy the pleasures of life, particularly wine. By extension, this type of poetry, which is very common in the Arab tradition, can be found in any text that praises the pleasures of wine. It could also come from the Qur’anic tradition, which links drinking to happiness when it evokes Paradise. It has also recently been suggested that the phrase could refer to Psalm 36:8, which says ‘And you will cause them to drink from the rivers of your pleasures’ (a suggestion we owe to Bahira Malak). However, to date we have found no other use of this epigraphic formula in the Castilian Arabic repertoire or in the tradition of al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), where most of these inscriptions originate. The word surur, meaning ‘joy’ or ‘happiness’, sometimes appears in inscriptions, but the allusion to drinking is not at all frequent. To better understand the originality of this inscription and the meaning it may have had for those who commissioned it, it is interesting to look more broadly at the use of Arabic inscriptions in Castilian architecture.

The first Arabic inscriptions appeared in the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula from the 11th century onwards, on objects or textiles and in a few churches. This phenomenon can be explained in part by the circulation of artefacts acquired peacefully through diplomatic exchanges, gifts and trade, but it was also the result of booty and trophies acquired by Christians during military contacts with Muslims. This circulation of objects encouraged the transfer of epigraphic motifs. At that time, the presence of Arabic in architecture was fairly limited and the texts did not accurately represent Arabic words.

It was mainly in the 13th century that Arabic inscriptions began to appear in religious buildings in the Toledo region, in Madrid and in the Monastery of las Huelgas in Burgos. The Christian conquests of Toledo in 1085 and the Guadalquivir basin in the mid-13th century led to the assimilation of the aesthetic codes of al-Andalus. For reasons of convenience, taste and fascination, but also out of a desire to dominate, the kings and nobles reused and transformed the palaces and mosques of al-Andalus and incorporated their ornamental motifs, including Arabic epigraphy. The presence of Muslim craftsmen encouraged the continuity of this know-how. The existence of an Arabised Christian community in Toledo made it possible to accept an Arabised culture that did not necessarily have Islamic connotations.

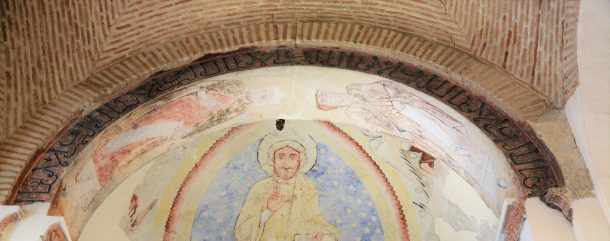

In fact, the Arabic texts that were used in inscriptions in Castile in the 13th century tended to be neutral formulas that could be adapted to a Christian context. None of the Arabic inscriptions in Castile contradicts the Christian faith. Most of the words used in this period refer to themes of happiness and well-being; these have a prophylactic value, to prevent diseases or repel bad luck. The most recurrent association of words is al-yumn wa’l-iqbal (“felicity and propitious destiny”), which is found in various inscriptions from 12th- and 13th-century al-Andalus and North Africa, even as far as Fatimid Egypt. From the thirteenth century onwards, this text became a stable and repetitive feature in Castile, almost always written in the same way in cursive calligraphy. It appears painted in white characters on a black background in the church of San Roman (image above), and in black characters on a red background on the apse arch of the church of Santa Cruz (Cristo de la Luz, image below) – both of these churches date from the first half of the 13th century. It is also carved into the stucco vaults of the eastern gallery of the cloister of San Fernando in the Monastery of las Huelgas in Burgos (dating from the second half of the 13th century).

The phrase can also be found painted on the wooden ceiling of the Santiago del Arrabal church (second half of the 13th century), along with another series of painted inscriptions that combine the same type of terms: al-yumn, al-salama, al-‘izza, al-karama (“felicity, peace, glory, generosity”). Here the calligraphic style is closer to the more angular Kufic script. These invocations are characteristic of Islamic epigraphy. They have a prophylactic value that they seem to retain in a Christian context, as shown by their omnipresence on the fabrics that wrapped the funerary remains of kings and queens. Similarly, formulae praising God or proclaiming his sovereignty and power are consistent in Christian religious buildings: for example, in the Monastery of las Huelgas we find the Kufic inscriptions al-mulk li-Llah (“sovereignty belongs to God”), or al-barakat min Allāh (“blessing comes from God”).

This repertoire expanded considerably in the 14th century, when the assimilation of the aesthetic codes of al-Andalus reached its apogee in Castile. Although it had been fashionable since the 13th century, Arabic epigraphy flourished above all in the second half of the 14th century, partly thanks to the initiative of Pedro I of Castile (r.1350–1369). Pedro built palaces in Astudillo, Tordesillas and, above all, Seville, in which Islamic art was reinterpreted in competition with the contemporary Alhambra in Granada. The same inscriptions can be found on both sides of the border. In Castile, they are most common in Seville, Toledo and Cordoba, in palaces, churches and synagogues. The repertoire of phrases increases, but they are always the same type of phrases that associate sovereignty, glory, happiness or health with adjectives referring to perfection, eternity or permanence: for example, al-mulk al-da’im li-llah, al-‘izz al-qa’im li-llah (“lasting sovereignty, permanent glory belong to God”). Whether God is mentioned or not, it is often He who is the source of these benefits.

Finally, there are poems or rhymed prose that also refer to divine protection. One example is ya thiqati ya amali anta al-raja anta wali, ikhtam bi-khayr ‘amali (“O my trust, you are my hope, you are my protector, seal my works with kindness”). This appears in the Alcázar of Seville, and in the Taller del Moro palace in Toledo, as well as in the Alhambra.

All these texts, which symbolically help to make the site a sacred space under God’s protection, are also ostentatious signs that contribute to the manifestation of power in palatial architecture. This is all the more so in the case of Pedro I, who had this phrase of praise displayed repeatedly on the walls of his Alcázar in Seville: ‘izz li-mawlana al-sultan don bidru ayyadahu Allah wa nasrahu (“Glory to our lord the sultan don Pedro, may God help and protect him”). This is directly modelled on the phrase that repeatedly adorns the walls of the Alhambra.

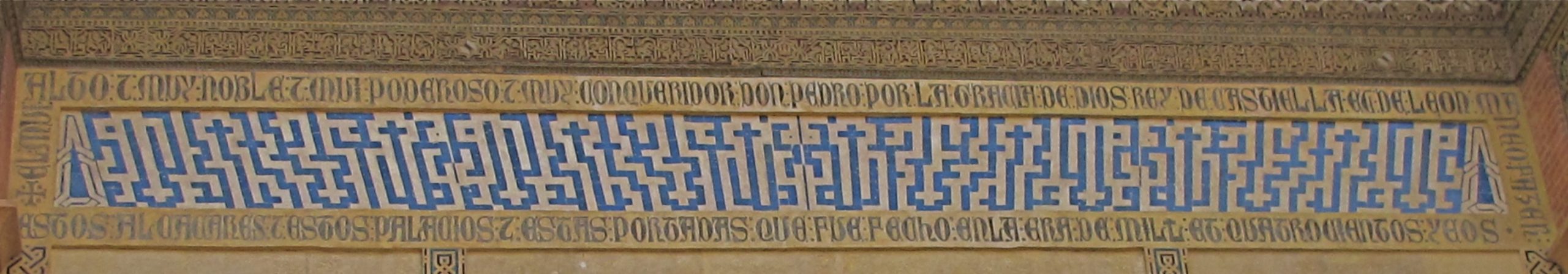

Pedro also appropriated the Nasrid sultans’ motto, wa la ghaliba illa Allah, “Only God is victorious”. This Nasrid motto notably appears on the façade of the Montería court of the Alcázar in Seville. It is presented in huge Kufic letters formed from blue and white ceramics that interlock to form the inscription, using a very specific technique that reaches its apogee here. This is mirror writing along both a vertical and horizontal axis. The complexity of its construction, combined with the refinement of the ornamentation that surrounds it, shows just how innovative Arabic epigraphy in Castile was. Its adoption by the Castilian sovereign also reflects the political dimension of these inscriptions and the Castilian desire for domination and hegemony over al-Andalus.

In the 15th century, Arabic epigraphy in Castilian architecture began to decline. It became less frequent and often contained errors linked to the loss of mastery of the Arabic language. Nevertheless, there were still some formal and textual innovations. For example, in the inscriptions on the arch of the Casa del Conde in Toledo, which dates from the 15th century, we can see precisely these characteristics of late epigraphy in Castile: a mixture between, on the one hand, a certain dexterity and notable innovations and on the other, clumsiness and even errors in forming certain letters. These inscriptions are highly original. One is a prayer to the Virgin Mary written in vernacular text but using the Arabic alphabet (a phenomenon known as aljamía): Santa María, a nos mejores (“Holy Mary, my best guide, make us better”). In addition to this linguistic originality, the calligraphy is complex, with overlapping and superimposed letters, and extended and intertwined stems. The other inscription repeats “Jesus son of Saint Mary” in alternating Arabic and aljamía. Although it is more legible, it has some formal and linguistic awkwardness.

These inscriptions, like many others, are difficult to read and it is unlikely that the building’s patron knew Arabic. Nevertheless, it was he who chose the content of the text and asked the craftsman to carve it – artistic choices were not left to the whim of craftsmen. But despite the difficulty of reading the Arabic language in the Hispanic kingdoms, we would be wrong to think that this diminished their function. We could ask the same questions in the Islamic context: even if the people spoke Arabic, they might still have found it difficult to understand texts that were elaborately designed and sometimes invisible from the ground. This is the paradox of ceremonial inscriptions in general, since they are difficult to decipher even though they contain a message that is intended to be understood. We need to distinguish between different levels of reception: a text that is often difficult to see, expressing specific concepts, and the general effect produced on the viewer, evoking an easily identifiable symbolism of sacrality, power, luxury and prestige.

Another example of particular interest, due to the originality of its form and the links it bears with our case of Torrijos, is the inscription on another palace built by Gutierre de Cárdenas, that of Ocaña, which also dates from the late 15th century. In the tower to the south-east of the palace, there is still a richly decorated ceiling, below which runs a wooden frieze with Arabic characters in relief and gilding. These are isolated signs with a geometric appearance, each of which seems to correspond to a word whose letters are arranged in an illegible manner. In the 19th century, the Arabist Pascual de Gayangos interpreted this inscription as the shahada, the Islamic profession of faith: “There is no God but God and Muhammad is his messenger”. However, this seems very difficult to decipher, and it would be surprising to find the profession of Muslim faith mentioning the Prophet Muhammad in a building constructed for a Christian patron.

This complex case also confirms that, beyond the legibility of the text, the inscription functions as an ostentatious sign of luxury and power designed to impress guests, but also to make them feel good. Indeed, this is what Torrijos’ inscription suggests, evoking the joy that guests are supposed to feel, a joy that encourages them to savour a nectar: wa tashrabūna min al-surūr (“You drink out of happiness”). Thus, combined with the rich ornamentation of the stucco on which the arabesques are displayed, and the ceiling simulating the vault of heaven, the Arabic inscriptions contribute to the display of pomp and splendour that probably took place during the palace receptions, and which must have delighted Gutierre and Teresa’s guests.