It’s now been a year since Clothworkers’ opened. To celebrate, we held a conference on the 23rd and 24th of October which looked at the breadth of new research emerging from the Centre. Across cultures and periods, from carpets to collaborations with twenty-first century fashion designers, the conference highlighted the huge range of research which has taken place over the past 12 months.

On the second day of the conference, Assistant Curators from the Asian and Textiles and Fashion Departments gave short talks about specific objects that they have been working on.

This post gives you a quick sense of the objects that we chose, and why – hope you enjoy it! (Watch out for the birth, marriage, death trifecta at the end).

Behnaz Atighi Moghaddam, Asian Department

The V&A houses a small but significant collection of Palestinian costumes at the Clothworkers’ Centre (for example: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O364465/womans-costume-unknown/). The outfits and accessories which I showed at the conference were traditional wedding attires which were used by residents of Ramallah and Bethlehem during wedding ceremonies and on special occasions. These examples demonstrate unique styles of embroidery and dress design used in different regions of Palestine. Bethlehem was the centre of fashion and Malak dresses such as the one seen in the image below were highly regarded and sought after by women all over the country.

Emma Rodgers, Asian Department

Beetle wings were traditionally used to embellish embroidery on textiles in South and South East Asia. The wing case from what are commonly called Jewel Beetles were used; either whole or cut into smaller shapes. They were prized for their iridescent green-blue colouring. The V&A has a significant collection of textiles decorated with this form of embroidery and, for the second day of the Clothworkers Conference, I chose a selection of 19th-century examples, made in India for both the Indian and European markets (for example: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O77263/dress-fabric-unknown/).

This embroidery was a very popular form of decoration for hats, scarfs, saris, and for ball dresses made for European women, where the reflective surface of the beetle wing pieces would have shimmered in the candlelight. The fragility of the embroidery, often sewn onto fine net and muslin, makes these textiles remarkable survivals of this craft.

Sarah Westbury, Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Department

The V&A has an incredible collection of textiles originating from Coptic burial sites in Egypt, dating from between 250-500 AD. Just five of these are socks, made using a technique that looks similar to modern knitting but uses just one threaded needle.

The only matching pair in the collection are on display in the Medieval and Renaissance Galleries; while the other three are in storage in the Clothworkers’ Centre. I have particular affection for the brown sock, 1243-1904, which on closer inspection proves to be made of more patches than original sock (http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O128875/sock-unknown/).

These beauties have been puzzling curators since they were excavated 100 years ago. We should spare a thought for the poor curator who in 1897 was faced with cataloguing the small conical piece on the right, and decided on ‘Dolls Hat’. As far as we can tell, it’s probably a ready-made patch to repair the toe of someone’s very holey sock.

Will Newton, Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Department

This matched gym set of white satin blouse and black satin knickers would have been worn by a member of the Women’s League of Health and Beauty (http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O361723/gym-set-unknown/).

The League, founded in 1930, was devoted to mass spectacle, world peace and ‘racial health’. The uniform was designed rationally according to founder Mary ‘Mollie’ Bagot Stack’s principles, allowing the freedom of movement needed to execute the League’s brand of synchronised exercises. Its briefness also encouraged what Stack called ‘skin-airing’, a cleansing process she thought best executed alone, in the nude. The uniform was widely copied by other women’s groups, such as the Legion of Health and Happiness and, notoriously, the Nazi Bund Deutscher Madel (League of German Girls), with whom the Women’s League were anachronistically (and occasionally contemporarily) associated.

Hanne Faurby, Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Department

For the Clothworkers’ Conference last week I choose to talk about two shawls. The first from Kashmir made ca. 1760 (http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O139698/shawl-unknown/) the second designed in Norwich ca. 1862 (http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O362894/shawl-unknown/).

These two shawls do at first glance appear very different. Yet, together they illustrate the nearly 100 years in which a high-quality shawl was a most desirable accessory – a statement of fashion, wealth and the propriety of its wearer. Over this 100-year span, shawl production in the UK (with centres in places such as Norwich, Edinburgh and Paisley) also demonstrates the extent to which the textile industry was taken over by the jacquard loom, becoming part of the industrial revolution in the 19th century.

Josephine Rout, Asian Department

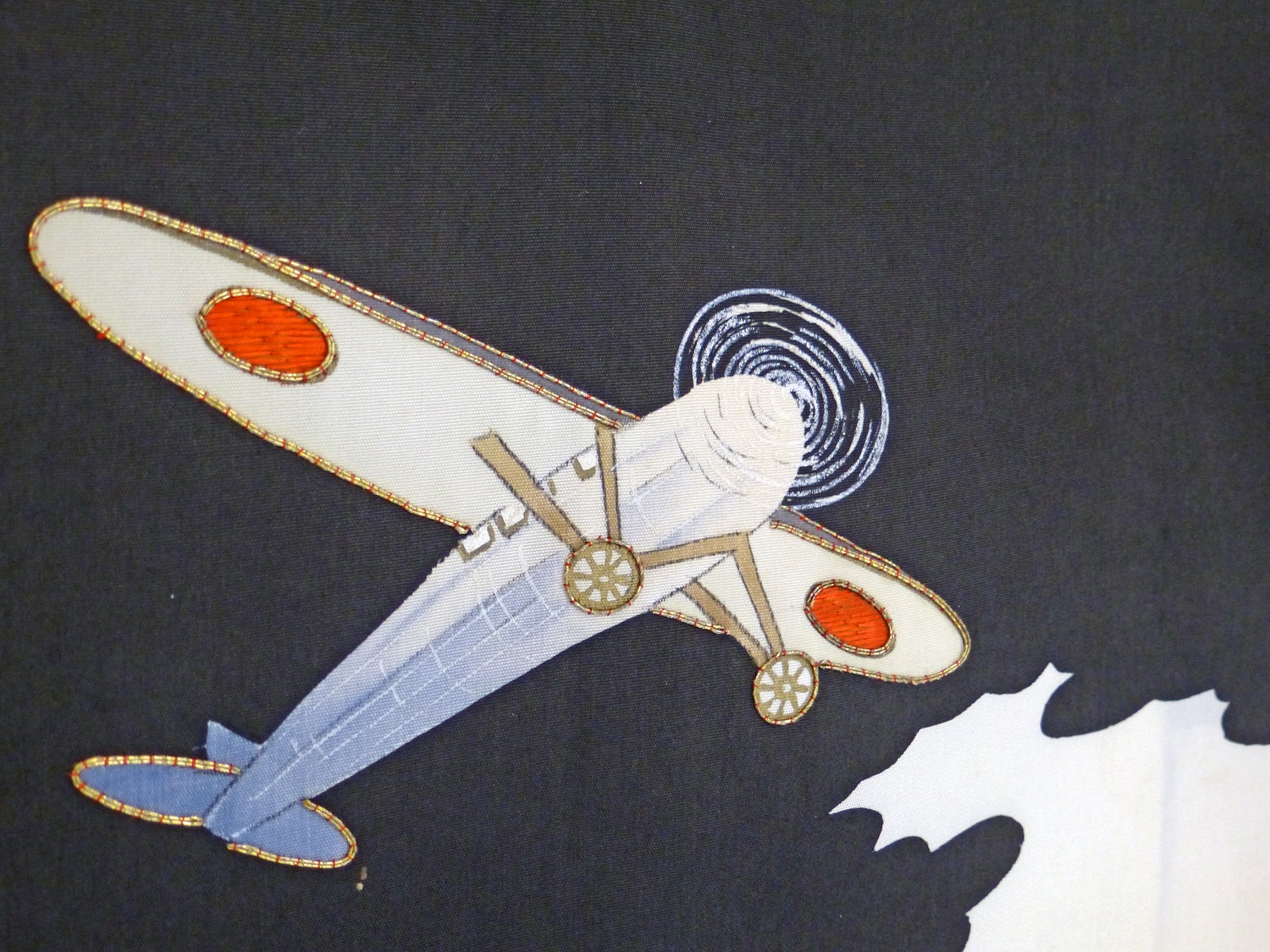

For my presentation, I chose an infant’s kimono that is used for the child’s first shrine visit (omiyamairi). The design is yuzen stencil dyed and painted within a white band (noshime), framed by black with supplementary embroidery on the flag, waves, anchor and roundels on the plane wings.

A recent acquisition, this kimono dates from between 1930-1945, when military propaganda designs gained popularity as the nation’s military activity increased. The image of battleships surging through the waves was a common motif for boys’ kimono at this time, replacing traditional imagery such as hawks, carp, or samurai helmets. The battleship can be read as a modern interpretation of the koi carp, an auspicious symbol for boys as they swim upstream, thus displaying strength, courage, energy, and determination. These attributes would not only make an upstanding citizen, but an ideal soldier. While perhaps a rather emotive object, it is important to remember that at this time women were encouraged to be ‘good wives and wise mothers’ (ryosai kenbo), by raising healthy and patriotic sons that would go on to become dutiful soldiers.

Xiaoxin Li, Asian Department

Ancient Chinese treated death very seriously, as evident by those lavish items used for burial purposes. The deceased was often dressed in their most luxurious garments, and for a period nobles even wore vests made of jade and precious metal. Quite the opposite, garments worn by those in mourning were made of hemp or jute in crude quality, as a representation of their sorrow. The exact type and quality of each mourning garment was determined by the relationship between the wearer and the deceased. This garment is relatively refined and is even decorated with silk thread and brass buttons, indicating that its wearer was a distant family member of the deceased (http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O485642/robe-cover-unknown/).

Lizzie Bisley, Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Department

Dating from the late 18th-century, elements of this lavish dress and accompanying filigree jewellery appear to have been worn as bridal costume by three women from the same Icelandic family (http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O115886/wedding-dress-unknown/).

The botanist William Jackson Hooker bought the dress in 1809 during a journey around Iceland. One of several elite Icelandic women’s costumes collected by British travellers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it is now the only known surviving example of its type. Although the dress is described in detail in the account that Hooker published of his travels, it was long believed to have been lost at sea when Hooker’s boat was shipwrecked on its return voyage to the U.K. The dress was the only thing to be rescued from the wreck and was bought by the South Kensington Museum in 1869 for the sizeable sum of £105. This dress offers a view into the ways textiles and dress were collected during formative years of the South Kensington Museum – highlighting the intersection between mid-nineteenth century cultures of science, art, design.